“We were having a real problem with video games in our house,” says Maureen L., a nurse practitioner and mother of two boys, ages 11 and 13. Immersed in gaming, her older son lost all interest in school and sports. “He didn’t care about anything else,” she says. “When he first started slipping in grades, I didn’t correlate the sixth-grade year with gaming.” Along came Fortnite, with its irresistible allure. Maureen says of her son’s seventh-grade year, “I couldn’t get him to play basketball, study for a test. All he wanted to do was video gaming … A year ago when [he] was playing Call of Duty, not everyone was playing. Now, everyone is playing Fortnite.”

Deeply concerned, Maureen sought help from the Charlotte-based organization, Families Managing Media. This past summer she pulled all video games. “I had to shut everything down,” she says. “The first four to six weeks were really hard. It was like watching somebody detox. I now know to say to any mom, ‘If you’re really worried, you may want some professional guidance.’”

Following her family’s “digital detox,” access to devices is permitted but tightly controlled, Maureen says. Both boys have smartphones, but she and her husband set up safety restrictions and turned off the camera, internet, and apps. She knows passwords to both phones and checks text messages daily. But Fortnite and other games? Those will stay off-limits. Maureen says she told her older son, “This is a health issue. It’s impacting your brain like a drug … For that reason, we can’t go back.”

How did he respond? “Once he realized, ‘She really isn’t bringing it back,’ he went on and started doing other things,” she says. “My son plays sports again. He reads books. He taught me to play chess. He’s gone fishing this summer. I just see him as more present in his own life.”

Is a backlash building?

As more families deal with the fallout from kids’ technology overuse — the kind that displaces other good or better things — is a backlash building? “I think the backlash is here,” says Melanie Hempe, a nurse, mother of four, and founder of Families Managing Media. Hempe, who conducts workshops on adolescent brain research for schools in addition to helping families, says, “I don’t think there’s any parent who would say that [having] unlimited screens is the best thing ever. Everybody’s talking about the problem … What people aren’t talking about is the solution.” She adds, “The only answer can be that we start to pull it back.”

Nationwide, some families are doing exactly that, banding together and telling kids the smartphone will have to wait. The Wait Until 8th movement, launched by a group of Austin, Texas moms, promotes a parent pledge promising to delay a child’s first smartphone until eighth grade or later. Parents have submitted nearly 10,000 pledges nationwide. Pledges are activated if at least 10 families in a child’s grade and school commit to wait.

Two Virginia public school teachers, Matt Miles and Joe Clement, have written the book Screen Schooled to challenge what they see as widespread technology overuse. Miles and Clement write that “screen saturation at home and school has created a wide range of cognitive and social deficits for young people.” Through their book and presentation materials, they recommend numerous changes, including limiting technology use in school and taking homework assignments offline whenever possible. They suggest schools should be “phone-free zones,” with phones staying in a student’s backpack, locker, or classroom “phone hotel” during the school day. Miles and Clement encourage parents to speak up if they believe schools are implementing technology “for technology’s sake,” and say “technology should work to enhance skills rather than replace them.”

When she shares brain research with schools, Hempe says she sees some fundamental misunderstandings. “The biggest gaps are from the administration,” she says; administrators seem to believe kids will be disadvantaged without “the latest and greatest in screens,” says Hempe, adding, “They believe that kids are changing. I don’t. They tend to believe that something magical is going to happen when you give kids a screen. I show the magical thing that is not going to happen.”

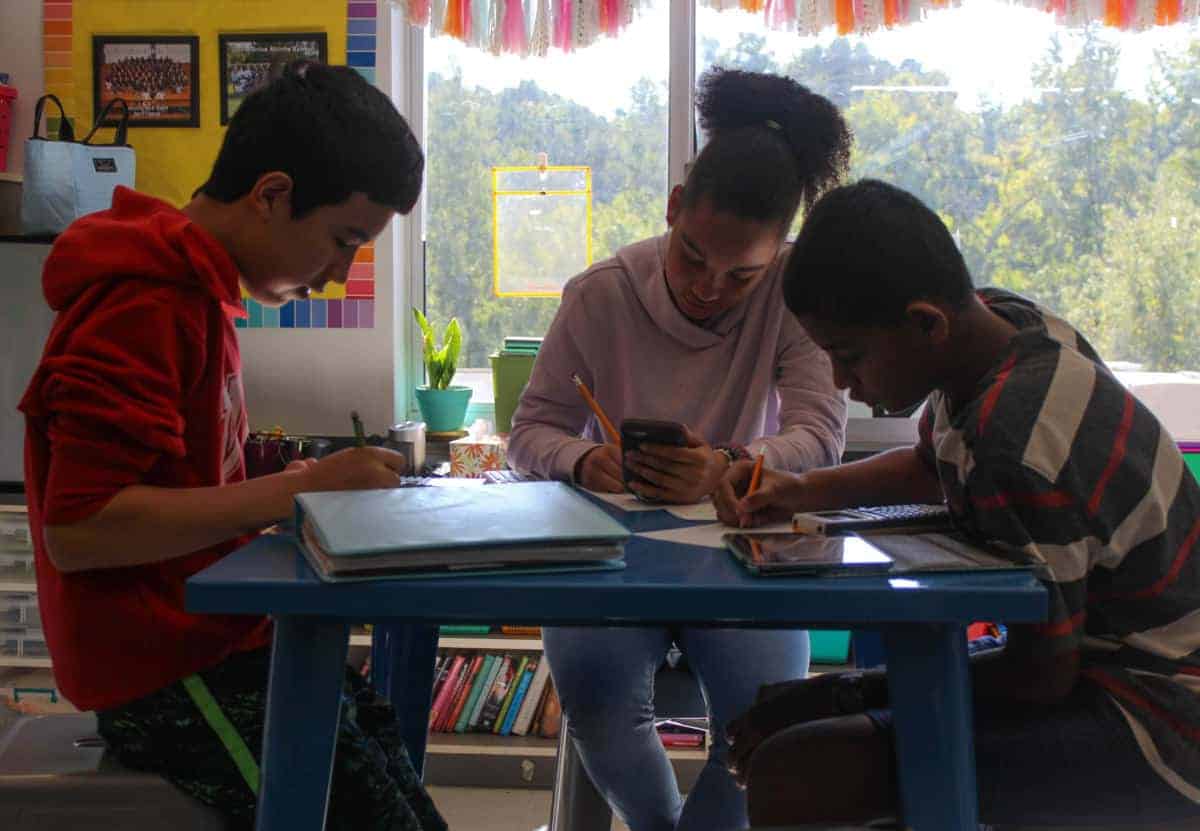

Her message to school administrators: “You use your screen in a very purposeful way. A child will never use a screen in that way.” She adds, “An open laptop facing a child on a desk? There is no better recipe for distraction on the planet.”

A school and family partnership

Is there a way to address some of these concerns and work toward better balance? To optimize digital tools when they augment — but do not replace — critical learning, and also encourage families to set healthy limits? Some savvy educators are laying the groundwork to do just that.

Of school-based technology use, Rick Williams, the principal at Davis Drive Middle School, says, “We try to limit it here — for enhancing instruction, using it as a tool for learning.” The school, in its fifth year of a “bring your own device” program, has been at it for a while. An advocate of firm, clear guidelines, Williams says, “Students crave some structure and some expectations. We’ve had students say to us, ‘Thank you for making me put my device away [so] I can focus,’ and maybe parents need to do something similar at home so expectations are clear. Students want some face time and want to be able to have those human interactions.” Adults have a central role to play in modeling breaks from screens, Williams says. “That’s just good healthy living. I think it’s our job as educators, it’s our job as parents, to help [kids] navigate this digital world. It’s ever-changing.”

Undergirding this work is a spirit of partnership. Williams says, “I tell my parents all the time, ‘We’re in this together … and we want to partner with you. If there [are] questions or concerns that you have, you need to bring them to our attention and we’re going to do the same.’” That partnership includes parent education and clear communication about technology use and misuse. “We have a fantastic student services department here with our counselors,” Williams says. “Not only do we provide parent sessions about technology but we also try to provide resources and information for parents about how to build better relationships with their children, how to recognize anxiety or stress in the household, how to help manage behavior at home. The biggest piece that counselors tell us — and that I certainly see — is when parents have that positive, open relationship with their kids and put in firm, strict rules around screen time, around expectations in the house. Those are successful families.”

Healthy media limits produce big benefits

Research supports what Williams promotes. Parents who set firm, consistent limits on media have children who perform better in school, are less aggressive, and get more sleep, evidence shows. Research also links parental media rules with lower rates of depression. What practical guidelines help families strive for balance? The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has compiled a list of tips for parents on healthy media use, including these suggestions and reminders: “Set limits; kids need and expect them,” and “create tech-free zones” at home that include mealtimes and kids’ bedrooms.

One strategy for optimizing sleep is surprisingly easy. “Parents can do something so simple,” says Dr. Kathleen Clarke-Pearson, a pediatrician and former member of AAP’s Council on Communications and Media and a board member of the Children’s Screen Time Action Network. “Take the cell phones and park them in the kitchen.”

Protecting learning also means limiting opportunities for media multitasking in class and at home, while kids do homework. Research shows media multitasking impairs learning and retention in both settings. Yet 60 percent of teens say they text — and half use social media or watch TV — as they complete homework assignments, according to Common Sense Media. Almost two-thirds insist their multitasking behavior doesn’t impact the quality of their work.

Their optimism is misplaced. A 2016 study by Matthew Cain found that teens who were heavy media multitaskers earned lower standardized test scores. They were more prone to impulsivity and demonstrated poorer working memory. What about grades? Checking social media while doing homework has been linked with a lower student GPA.

Debate over the power and pitfalls of technology, at home and school, is sure to continue. But balance won’t come unless adults lead the way, says Maureen L. “My 13-year-old is taller than me,” she says. “In middle school, [kids] start looking like little adults, and we think we can talk to them that way.” But they still need adult guidance in learning about balanced and responsible technology use. “We know it with everything else. [But] we’re handing them technology with no brakes, expecting them to put the brakes on,” she says. “We’re putting too much responsibility on the kids to ask them to manage this.”