This is part 1 of a five-part series documenting the history of the Winton Triangle community and the C.S. Brown School. It’s a story about the struggles that befell a pioneering community and the values that survive all these centuries later to sustain hope for the future. Read the rest of the series here.

It isn’t at all surprising that centuries ago, people of color in a rural, northeastern North Carolina community picked cotton and grew tobacco. What is surprising is that these free families of color owned the farms where they picked the cotton. They owned the land where they grew the tobacco. They owned the businesses that sold goods and traded with white people in the area.

And amazingly, it happened in the 1700s, before either the Civil War or the American Revolution.1

They were part of a multiracial community of Indigenous, Black, and white people, living in a region spanning Winton, Cofield, and Ahoskie. It would be called the Winton Triangle.2 Though not immune to racial tensions, this area was established together by people of different races who planted a pioneering seed bearing fruit within the Black community now.

“There was a more progressive attitude here than in the rest of the South,” said Marvin Tupper Jones, a Cofield native and historian at the Chowan Discovery Group.

The men and women of color built churches, some of the first in the state for Blacks.3 They started businesses. Some were the first entrepreneurs of color in the nation.4 They created a destination in Winton where people of color vacationed and watched the likes of James Brown, Sam Cooke, and B.B. King perform in North Carolina’s tiny port town.5

They established schools. They established the school.

But first, the story about these people and that triangle of towns — a community built on values of self-sufficiency and service. Although economically strangled by forces both outside and within, this community retains its self-determining and caring spirit. It is a story worth knowing.

How a community of color thrived during pre-Civil War times

The first inhabitants of the Winton Triangle were Indigenous people of the Chowanoke, Tuscarora and Meherrin tribes who lived off the Chowan River and creeks nearby.6 The first settlers of European descent arrived on expeditions from the Jamestown and Roanoke colonies in the 1580s. People of African descent probably came with them — some free, others enslaved — though Jones says the records are unclear.7

Most written records from this time are long gone, a casualty of when the Union Army made Winton the first town burned to the ground during the Civil War.8 A record that did survive identifies the first landowner of color, Thomas Archer, dated in the 1740s.9

Landowners of color owned 50-acre farms that stretched throughout the region and stores along what would become Winton’s Main Street.10 Most of these first landowners of color were mixed race, referring to themselves simply as people of color.11 Many Blacks claimed Native heritage.12 Many had a white parent or white ancestry, which is why these free people of color were known for their complexion.

In a book he co-authored with Dudley Flood, Winton-native Ben Watford recalled a conversation with a stranger he met golfing in New Jersey.13

“I know Winton,” the golfing companion said. “The [B]lack people there are light bright and damn near white.”14

Complexion partly drove the acceptance of residents of color.15 But it wasn’t the only driving force. It also helped that North Carolina was barely settled in the 1700s. There were few known laws and, until the 1830s, little enforcement of whatever laws existed.16

There was also an interdependence among the people settling the area together. People of color married, raised children, and attended school with whites in the community.17 Most free people of color in the early Winton Triangle were multi-skilled — as carpenters, artisans, blacksmiths, and farmers. Their skills were essential to establishing and growing the community.

“It helped that the white neighbors were on the same level as these free people of color, economically,” Jones said. “They needed each other — for building, for repairing, and just to grow. You had cooperation.”

The shifting racial landscape and a school that kept the community growing

The community started constructing school buildings in the 1860s. There wasn’t an emphasis on segregating schools early on. Schools were private, and teachers were paid per student. White teachers welcomed students of color, if for no other reason than the income helped make ends meet.18

By the late 1800s, if people of color wanted higher education, they had to leave the area for Raleigh or Hampton, Virginia. The community wanted to grow and keep its own future leaders.19

Social and political pressures helped make this a priority. Slaveowners had always existed in the area.20 But as demand for cotton and tobacco increased leading up to the Civil War, so too did demand for enslaved labor and higher profit. According to the 1860 census, slaves made up 47% of Hertford County’s population of 9,504. Free people of color comprised about 12% of the population.

Following the Civil War, discriminatory laws known as “black codes” aimed at controlling newly-freed slaves sent fissures through the community. 21

Amid this shifting landscape, free Blacks in the Winton Triangle established the Chowan Education Association to focus on the advancement of people of color through education. They founded a school called Chowan Academy in 1886.22

That’s the school.

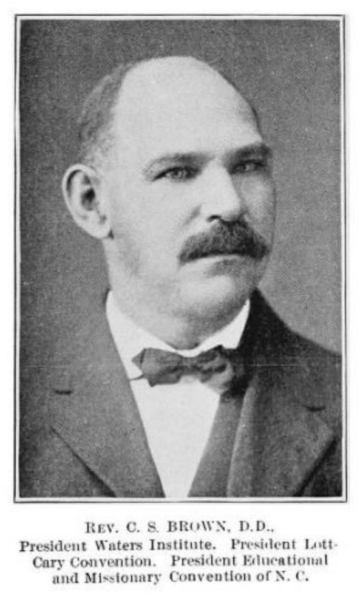

It’s also been known as Winton Academy and later the Waters Institute. Throughout its history, it served as a private college, a teacher preparatory school, a public K-12 school, and finally a high school. Today, people just call it C.S. Brown. It’s named after the man tapped to lead it from the beginning, a Scots-Irish and African man named Calvin Scott Brown.23

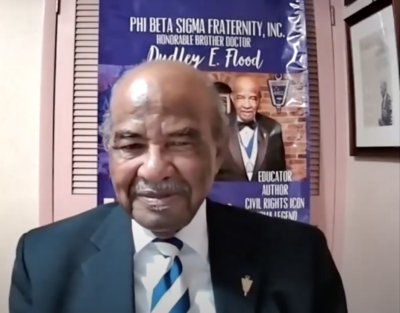

“It was the only boarding school for African Americans in the country, as far as we knew,” said Dudley Flood, an education pioneer in North Carolina who grew up and lived in Winton from the 1930s through the 1960s.

“And it was built by the people, the African American people and the Native American people. Of course, at that time, they were just people of color. You didn’t think of yourself as any other way.”

Brown was the pastor at five churches. And he was principal of the school until he died in 1936.24

“The school could have failed under another leader,” Jones said. “He made it a success even through hard times. He gave Winton this economic engine that brought more and more people here.”

This economic engine of the early 1900s wasn’t about making folks rich, though. It was about building stability and self-sufficiency. That’s what Flood remembers.

The self-sufficient people of Winton

Flood was born in Winton in 1932.25 He said there was little focus on wealth when he was growing up. Many of the Blacks in the community were a free people from the start, and above money, Flood says they valued independence.

“The economy there was fairly mundane,” he said. “If you owned a home, then your ambition was to have that home free and clear, with the mortgage paid off by your middle years. Have your car paid for. Have a little piece of money in the bank.”

In addition to owning farms and stores in the area, many people of color worked at a timber plant outside of Winton or on the banks of the Chowan River.26 The river is 30 feet deep and 750 feet wide at Winton, and large vessels would come in frequently to bring goods or carry out raw materials. The ship passengers added to the community’s culture, Flood remembers.

“Even though the town of Winton had fewer than 1,000 people in it, you never thought of yourself as being that small,” Flood said. “There was so much interaction with people from other places.”

If folks in town needed extra money, they would find odd jobs doing work for people around town.

“But all of it had value, had dignity,” Flood said. “We didn’t degrade somebody who was doing anything for extra money.”

Education was valued, but there were no societal pressures around it. Most teenagers went to the high school, and by the time they were juniors, they knew whether they wanted higher education or to go straight to work. Neither option was viewed superior.27

“By the time I was leaving, which I did in 1967, we had begun to have a little more focus on wealth,” Flood said. “But wealth was reasonably well distributed at that time. And in the middle class were teachers and ministers, undertakers. And because it was a dual society, Blacks had about the same percentage of those as white society had.”

A place known for tolerance

Flood says the distribution of wealth, and his mostly pleasant experiences growing up in the area, color his fond memories of growing up in Winton. Still, he acknowledges that not every person of color was treated similarly during the Jim Crow era.

When the nation rationed goods during World War II, it wasn’t uncommon for white store owners to reserve rations only for white people. It was also common to see a white employer pick up a Black home worker and make them sit in the back of an otherwise empty car.28

Often, the difference between a positive or negative experience for a Black person in Winton, Ahoskie or Cofield those days had much to do with skin tone.29 In the book they co-author, Flood and Watford demonstrate that. Unlike Flood, Watford was excited to leave Winton in his youth and never wanted to return. He attributes that to his treatment due to his darker complexion. 30

At the same time, Flood remembers walking downtown as a child and having the town’s mayor, a white man, frequently pick him up and give him a hug. He grew up unsurprised that Black people owned land or businesses. It seemed natural, to him, that whites and Blacks lived next door to each other because there were no segregated neighborhoods in town.

“There was no distribution of wealth that we thought was ever not available to us,” Flood said.

In fact, the area was known far beyond its borders for tolerance and prosperity — so much so that a developer created a successful 400-acre destination for middle-class people of color called Chowan Beach. In the 1950s, it attracted visitors from all over, as well as leading Black musicians who traveled the Chitlin’ Circuit — a collection of venues where it was safe for Black entertainers to perform during Jim Crow.31

“There were certainly some unpleasant experiences along the way,” Flood said, “but the positive far outweighed the negative for me.”

A school at the center of the community

One of these positives, Flood says, was C.S. Brown. Long before Flood walked its halls, Calvin Scott Brown had established a powerhouse school. What began as a private boarding school became the very first standalone high school for African-Americans in the state.32

It was turning out politicians, pastors, doctors, authors, and state leaders — including Flood, who was instrumental in leading the state’s desegregation efforts after leaving Winton.33

The school was impacting the community economically, too. It was bringing students into town, some of whom rented rooms in nearby homes. Importantly, it brought in lots of teachers. Two-story homes went up on both sides of Winton’s Main Street. Most were owned by people of color, and almost every one housed at least one teacher at C.S. Brown.34

Everybody from the area wanted to attend C.S. Brown.

“I went to elementary school at the C.S. Brown,” says Michael Perry, his voice ringing with pride. Perry grew up on the outskirts of Winton and later became superintendent of Hertford County Public Schools from 2012 to 2015.

It was a K-12 public school when Perry first started attending in the 1960s, and he remembers watching the high schoolers. He was especially enamored with the marching band and its drum major, a man named J. Wendell Hall. Today, Hall serves as a member of the State Board of Education and has spent nearly 20 years on the Hertford County Board of Education.

“Everybody wanted to be in the [high school] band,” Perry said. “… I wanted to be the drum major.”

Perry never did attend high school at C.S. Brown. When the state desegregated schools, Perry was sent to Murfreesboro in 1971.

“I cried when I had to leave,” he said.

Hard times for the community and the school

The farms of the Winton Triangle produced abundant cotton, corn, and soybeans. They even played a large role in North Carolina’s status as a leading grower of tobacco.35

But the world was changing. Flood remembers seeing it first with the farms around the 1950s. The dollar was strong, which led to a drop in commodity prices. And as profits per acre dipped, the 50-acre farm was less able to support a family, Flood recalled. Technological advances produced equipment that reduced the labor cost of farming, so the wealthy could buy six of those family farms and turn tidy profits off 300 acres.

Flood remembers seeing the pioneering landowners of color begin to sell their farms, dropping the enrollment pool for C.S. Brown.

“The mule died and the horse died, and you just had the tractor,” Flood said. “And that didn’t last long before you needed something bigger. So we went away from farming to agribusiness, and that began to consolidate the wealth in the hands of a few people.”

When Hertford County desegregated public schools in 1970, C.S. Brown lost more enrollment.36 Starting in 1971, kids of high school age went off to Ahoskie and nearby Murfreesboro. C.S. Brown ceased its high school operations the following year, hosting grades K-8 only.

Three years later, in 1974, the community received yet another blow that would impact C.S. Brown enrollment. The highway, U.S. 13, formed the spine of Winton’s downtown. For that one-mile stretch, it was called Main Street and boasted most businesses and the town’s one stoplight.

Then the state built a bypass around Winton, and businesses suffered terribly from loss of through-traffic.37

“Once they moved the road, I saw the town really started dying,” Perry said. “I was still there as a student during that time, and the road used to come right through the town. When your town is put on a bypass, and the truckers and everything else is no longer coming through, we saw houses beginning to be boarded and businesses closing. Because that was a lifeline.”

Winton lost its only stoplight. The docks closed, and commercial shipping vessels stopped coming, too — a byproduct of many things, including overfishing and development of faster modes of transportation.38

“Crime is more of a problem now,” Jones said. “Opportunities are scarce. And the best jobs in the county are held by commuters who don’t even live in the towns.”

When families left the area, C.S. Brown’s enrollment plummeted. The school had already weathered turbulent times, but it was on the brink of becoming a vacant building by the turn of the millennium.

With its existence in peril, it looked first for help from Hertford County, heirs to the self-determining and service-oriented spirit of the Winton Triangle people. It also got an assist from a man raised just an hour away, in another historic community.

Behind the Story

Rupen started working on this story in August 2020, making more than 10 trips to Hertford County during the course of his reporting. His research included review of state archive documents, university documents, books, newspaper articles and interviews with 13 sources. In the interest of historical accuracy, the first article in this series was reviewed by Winton Triangle native and historian Marvin Tupper Jones.

What began as a desire to profile a high school principal in one of the majority-Black counties in our state turned into a five-article series as Rupen chased threads and discovered the richness of the Winton Triangle and the C.S. Brown School. In total, Rupen spent more than 200 hours on this story of hope.