The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI) has been working on a new framework for the state’s schools.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), a piece of federal legislation passed in December 2015, gives schools funding and relative flexibility to determine how their systems are run — and held accountable.

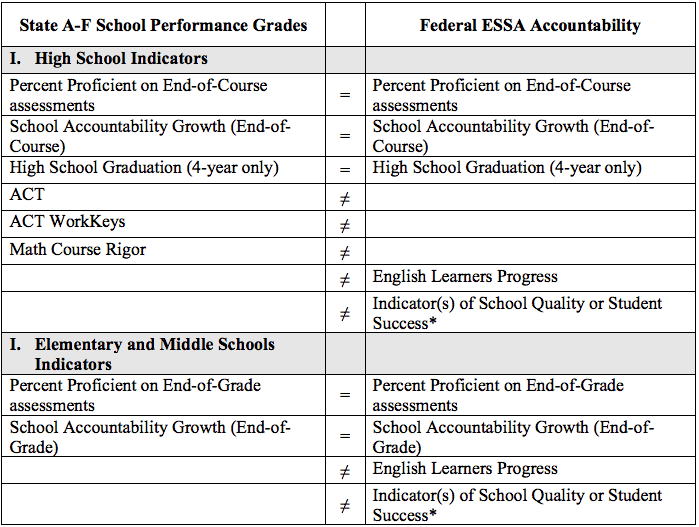

North Carolina’s current accountability system, which grades each public school on an A-F scale, doesn’t match ESSA’s requirements.

Right now, a draft of the state’s ESSA plan is online but leaves considerable gaps and questions. The U.S. Department of Education released updated requirements on Nov. 28, which are largely looser than what the department originally laid out.

At the State Board of Education’s December meeting, proposed accountability models were provided online for elementary, middle, and high schools — but weren’t approved. These have been revised by DPI as staff have received feedback from educators across the state. The official accountability models and entire plan have to be submitted no later than September 18, 2017.

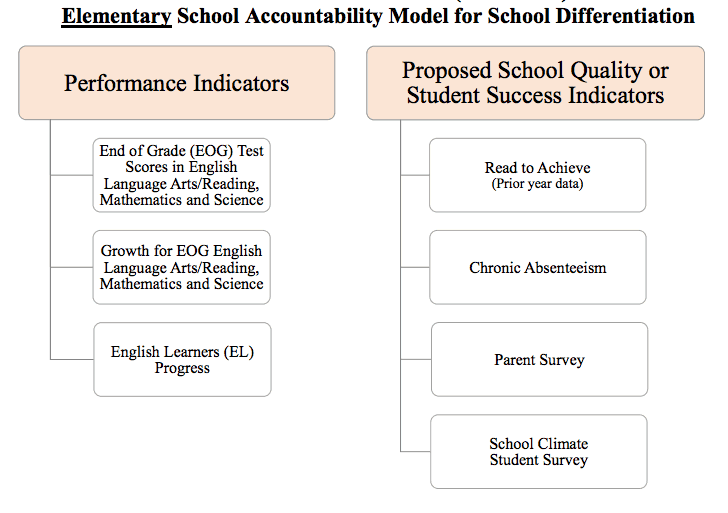

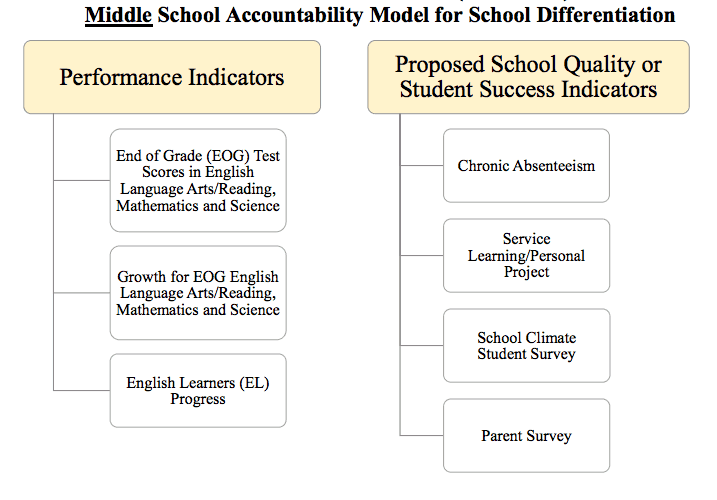

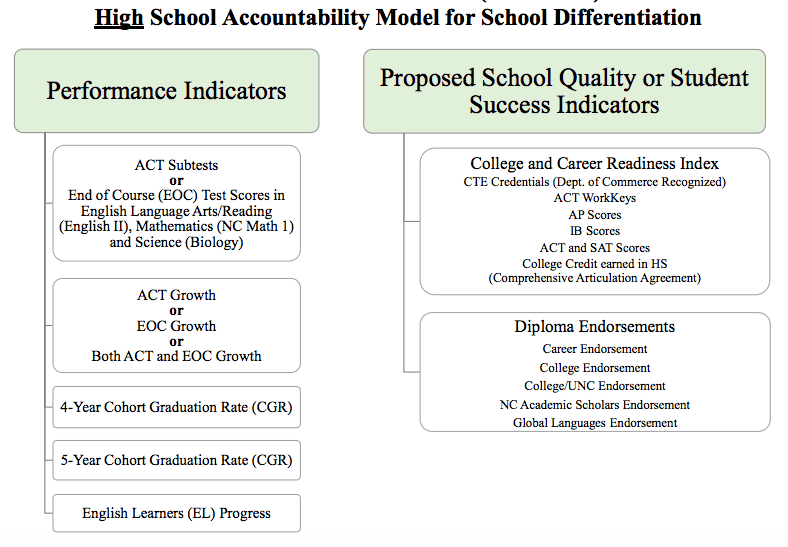

Below, you can see charts of the proposed accountability models. On the left, there are performance indicators. These should be designed to reflect student outcomes. There are four main indicators the state is considering so far: test scores, student growth from year to year, English Learners Progress — which is a new ESSA requirement — and graduation rates for high school.

On the right, you’ll find school quality or student success indicators. These should be designed to get at the other things that make schools great, or not so great. Things like school climate and culture, community involvement, and character development. The U.S. Department of Education, in its most recent regulations, said this indicator can be anything that research has shown has a positive impact on student learning.

Let’s take a step back, and look at why a new system is even needed. Here’s what doesn’t match between the state’s A-F system and the new requirements. Below is a chart created by DPI to explain the differences between the two to the State Board.

In all three cases — the systems for elementary, middle and high school — English Learners Progress and at least one indicator of school quality or student success is missing. The asterisks following the school quality or student success indicators indicate an explanation in the document of what the indicators are and that they must, according to ESSA, “meaningfully differentiate” between schools. The document also gives examples of possible school quality or student success indicators, like school climate and safety, student or educator engagement, access to advanced coursework, postsecondary readiness, chronic absenteeism, and dropout rates.

In an interview with EducationNC, DPI’s director of accountability services Tammy Howard made it clear that these new requirements don’t necessarily mean the A-F grading system will change or be wiped out.

“That’s a policymaker decision,” Howard said.

In an interview prior to January, Superintendent of Public Instruction June Atkinson said the state has the authority to have two systems. The General Assembly will likely take up the issue in their next long session, which starts in January. Any change in the A-F system will have to be made legislatively.

In the meantime, the State Board has been discussing possibilities. They’ve been asking questions: What do we like about our current system that we want to keep? What do we want to change?

And probably the most important question: What do the people of North Carolina think?

Over the past nine months, education leaders have been meeting with teachers, principals, and education stakeholders to get feedback and ask for suggestions.

Atkinson had talked to people in, she estimated, 40 to 60 different meetings, focus groups, town halls, and conference calls since ESSA was passed. Atkinson said that’s still not enough — that feedback needs to continue to shape the system between now and next September, regardless of the fact that a new Superintendent, Mark Johnson, is now in charge.

“People want the accountability system to go beyond a test score,” Atkinson said. She said she kept hearing those words, but when it came to finding indicators to make that happen, Atkinson said most people didn’t know how.

“It’s hard to identify an accountability measure that would differentiate school success, that could be disaggregated by student, and that could be used as a basis to helping schools improve,” she said.

Atkinson said there have been six guiding principles that DPI and the Board have been using throughout this process:

- The indicators should be research-based.

- The indicators should be capable of differentiating student and school success.

- The data should be tagged to individual students.

- The indicators should not be a surrogate for poverty.

- The data can be collected and compiled at the local and state level.

- The indicators are meaningful in order to improve schools for students.

NC Teacher of the Year Bobbie Cavnar sits on the State Board as an advisor. He said he’s heard two consistent concerns from teachers throughout the state.

One, performance indicators shouldn’t be code for poverty detectors.

“We know already that 98 percent of failing schools in North Carolina are high-poverty schools,” Cavnar said. “We want to make sure that we’re demonstrating the quality of education provided to students, within the confines of the community that they’re in.”

Often, student achievement — which constitutes 80 percent of a school’s A-F grade — strongly correlates with the poverty levels of a school’s population.

“Proficiency standards do not say anything about how far a teacher brought a student,” Cavnar said.

End of Grade test scores in language arts, math, and science are included for elementary and middle school in the proposed models, and ACT/End of Course test scores are part of the proposed high school model. This is an ESSA requirement. DPI has yet to determine the weight of these proficiency standards for the new system.

Cavnar said attendance rates also often signify other present social concerns rather than simply measuring education quality.

Students Can’t Wait, a project by several education advocacy organizations that weighs the pros and cons of different indicators, does mention that chronic absenteeism is especially higher in low-income students. Chronic absenteeism is one of the indicators included in DPI’s proposed elementary and middle school models.

But Students Can’t Wait also says “research is clear that schools and districts can impact students’ absenteeism rates.” Atkinson insisted that the indicator goes beyond poverty and is a red flag for schools to intervene early on.

“I know poverty has something to do with it,” Atkinson said. “But there’s also chronic absenteeism beyond children who live in poverty.”

The second concern Cavnar said he heard consistently was that each state school — just like each child — is different.

“What we as teachers do is we meet the needs of communities and students,” Cavnar said. “The difficulty of grading things like that is to try to find something that’s exactly the same across the entire state of North Carolina.”

“We have thousands of examples of great programs we’ve put into place that are unique to our school or district,” he said. “That’s really difficult for a teacher to hear — that we can’t include that because it’s not true of every school.”

During the State Board’s meeting in Boone back in July, members and advisors broke into small groups, brainstormed, and debated as facilitators wrote their ideas on large sticky notes.

From those discussions, there was one idea that many were excited about and rallied behind, an idea Cavnar said might account for the uniqueness of schools in a consistent way: a service-learning project.

You’ll find this project in the proposed middle school model. Cavnar explained that this could be anything from a community garden to a play to project-based learning in a teacher’s curriculum every day.

This project would also bring community involvement into the picture. It’s inline with the State Board’s recent commitment to the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model, which they passed at their October meeting and emphasizes collaboration between health and education, and making schools a setting where children can find holistic fulfillment.

“It’s looking at how that school is working with the community to get services they need,” Cavnar said. “It’s thinking of schools as a hub for services for children.”

Any member of the public can provide input on the state’s ESSA plan on DPI’s website.