“Why did you go into education?” asked the facilitator.

It was the first day of professional development during my first year of teaching. Luckily, I positioned myself in the room where I knew I was not going to be first to answer. As I thought about my answer, I could not help but think of all the canned and typical answers I was accustomed to hearing:

“It’s the family business.”

“I had an amazing teacher in school that inspired me to be.”

“I took this class in college…” and so on.

I had my canned answer ready to go as well, but when it was my turn, I paused and said something that I had always thought but never said aloud: “Because I didn’t have a teacher who looked like me.”

Talk about killing the mood, but that was my truth.

I have my own hold ups on my racial and ethnic identity, and the more I learn, the more it evolves. I grew up knowing that I had two parents that were from Colombia and that made me Colombian (by the way, Colombia is spelled with an “o” and not a “u”), but I could never find that on any standardized test or government form. Not knowing what to fill out, I asked.

“Well, Dayson, you’ll fill in the circle next to Hispanic and under race…um…well… just fill in Caucasian.”

And that was that. My primary school experience was mostly in New Jersey in very diverse neighborhoods and schools. My mom had divorced my father and continues to be the exemplar of a fierce and determined Latina. Her second marriage was to a white man, who I consider more of a father than my biological father.

We moved to North Carolina right before the Latino population boom in Alamance County, to the outskirts of a small city whose school system has just merged with its county schools. Our address determined that I would be going to a rural school in the southern part of the county. Something this kid who was born in Queens, New York, was not prepared for.

The very first time I can remember feeling bad about my identity was when I was in 6th grade when a peer called me a “wetback.” I knew what the word meant — it was not the first time I heard it — but it was the first time it was directed at me. I was overcome with all sort of emotions and I handled it like most 6th graders do: I cried.

Then I decided I needed to do something about it. Having survived many encounters with my mom’s chancla, I knew I probably should not have any direct confrontation with the student. I went to the office and told the principal. Surely, he would not let this injustice stand at his school. I recount what happened, with tears rolling down my chubby cheeks. He said that, unfortunately, there was nothing he could do, since no one witnessed it. He added that it is probably something I should get used to.

This moment affected the rest of my middle and high school experience. I did not even feel Latino enough when I went to college to join the Hispanic student organization. I anglicized my name because it’s easier to pronounce. Yup, that’s it, like Jason but with a “D.” Sigh. I stopped listening to cumbia and salsa. Worst of all, I stopped speaking my language. The first language I learned. The language of my family. I tried to do all I could to be just like my white peers, all the while losing, piece-by-piece, my latinidad.

This trauma is long-lasting and I still have moments where I think that I’m not Latino enough; I am an imposter. Looking back, I wonder what it would have been like if I had a teacher that looked like me, a teacher that I could relate to. A role model of someone who was proud of their latinidad and was someone that I could aspire to be. Would I have been so quick to try to blend in?

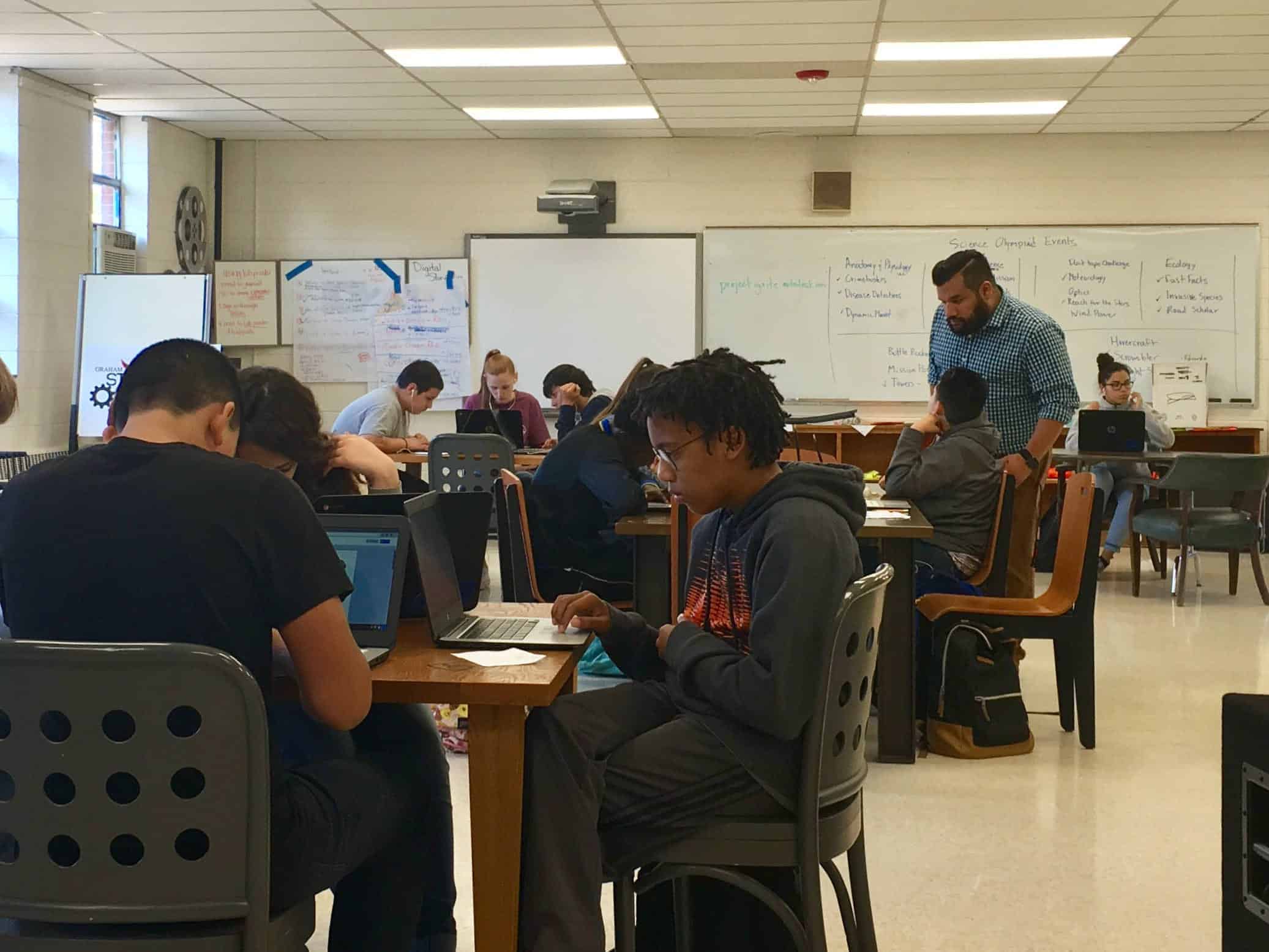

That is why I do the work I do. Looking back through yearbooks, there have been Latinx educators but they have been Spanish teachers, the very thing that I was trying to minimize. Why couldn’t there be a science teacher, counselor, or administrator who also happened to be Latino? I have come back to teach in the system where I was a student and unfortunately while I recognize more Latinx professionals in our school buildings, they still seem to be in roles that society is accustomed to them being in, and the number of Latinx students in our schools is steadily increasing. These students, who over the past eight years have taught me que yo soy latino, who smile when I say “Claro, que puedo hablar español,” who beg me to play our music.

I’m breaking the mold, orgulloso de ser latino, and I need more of us to rise up. ¿Estás listo?