I spent the entirety of my six-year teaching career in the urban education setting and absolutely loved it. My classroom was filled with jumpy, brilliant, often immature ninth-graders, the vast majority of whom were black and brown. By the numbers, this population and grade-level would appear to be the most “problematic,” representing the bulk of suspensions according to the most recent statewide discipline data.

I wouldn’t say my experience was easy by any stretch. It takes real skill and intestinal fortitude to hold your own as an instructor. Like most teachers, I had particular students who routinely challenged my classroom management and made it hard to teach. However, rarely if ever did I have to write a referral or call the front office. In short, most situations weren’t that serious and could be handled on the spot with some level of intervention. So, when I see the same populations I once served disportionately receiving exclusionary discipline, I have to ask the fundamental question “why?”

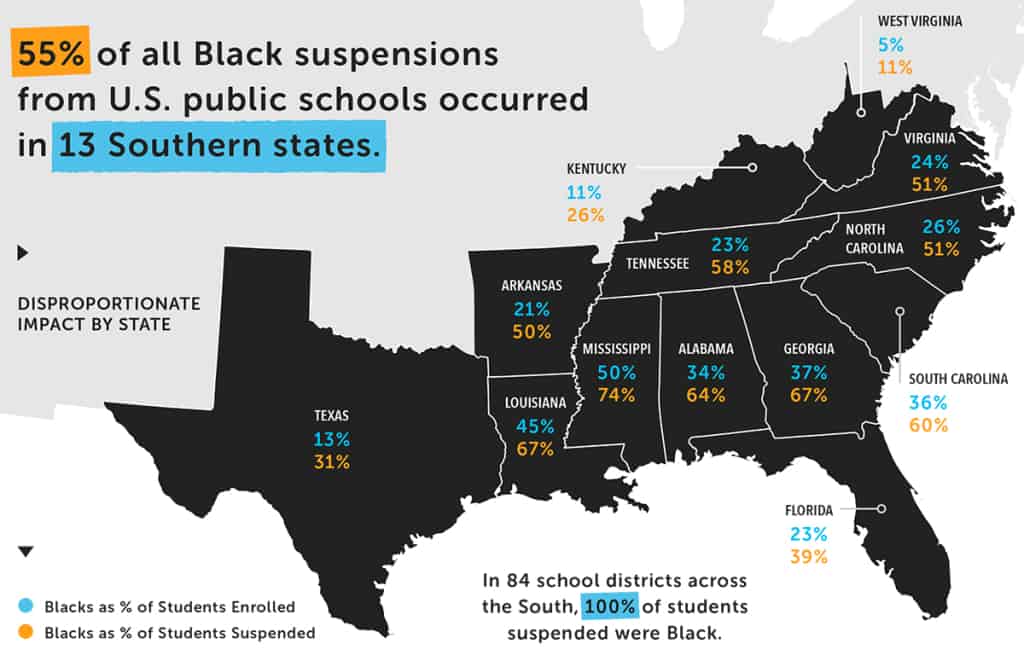

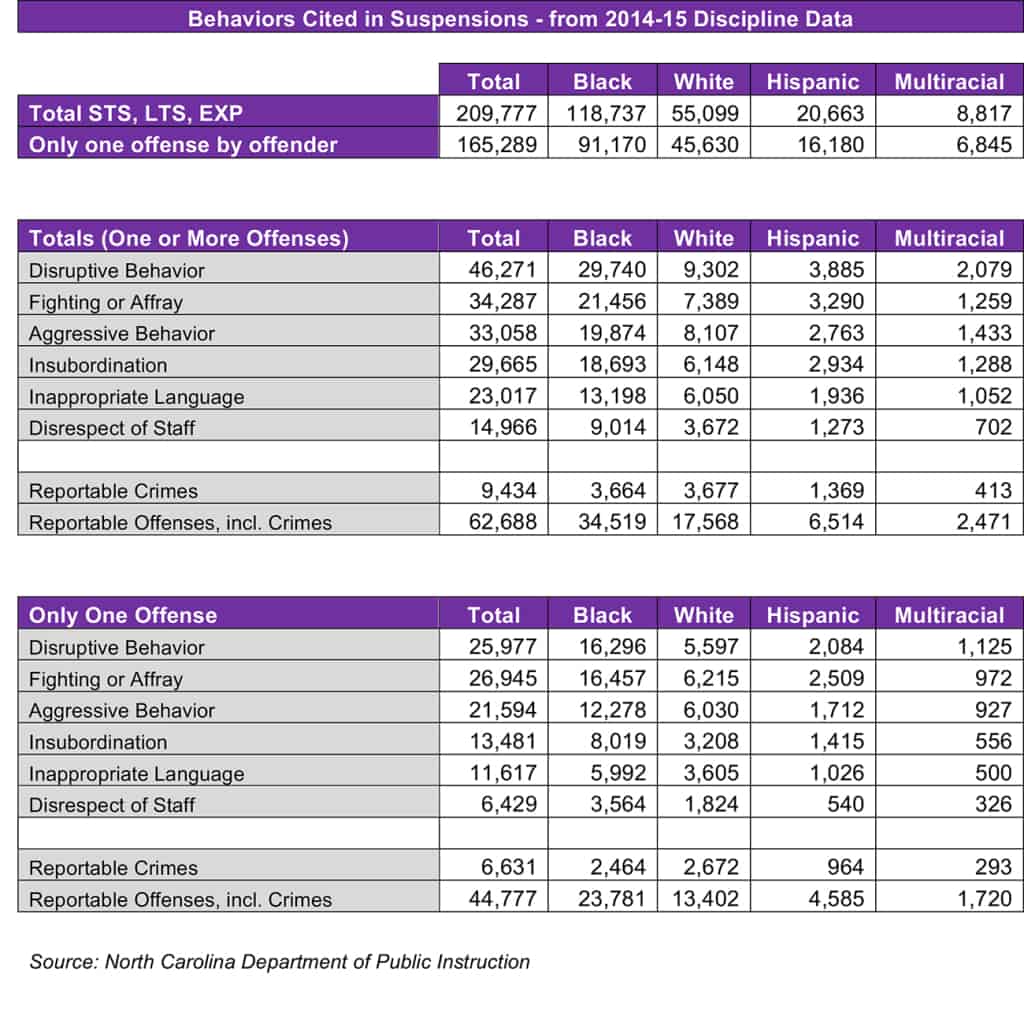

As the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction recently released its consolidated discipline report, we continue to see a disturbing pattern. Students of color have significantly higher rates of both short- and long-term suspensions than their white counterparts in North Carolina schools. This is unfortunately nothing new and consistent with a national trend, but particularly pronounced in the southern region of the country.

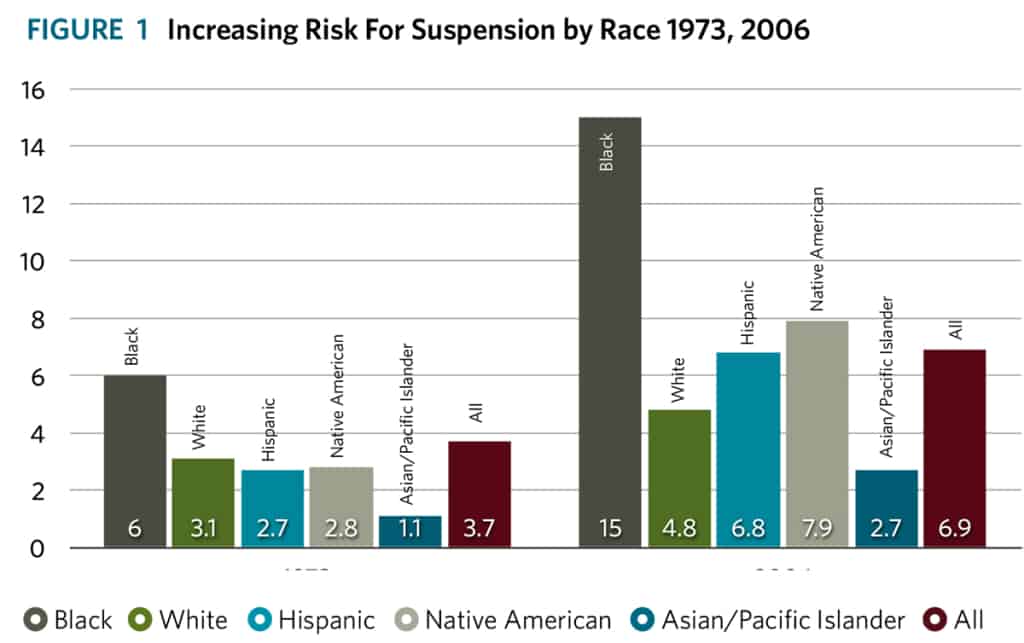

I trust that I don’t have to provide the reason for why this is historically significant. American Indian, Hispanic, multi-racial and black students have for some time experienced higher rates of suspension since the beginning of desegregation efforts in the early 1970s. So, racial discipline gaps are nothing new. While this data point is glaring, the issue is rarely if ever addressed as a problem by policy-making bodies.

North Carolina on the one hand is to be applauded for having consistently lowered the overall instances of suspension and expulsions over the past several years (with exception to this past year). This has come largely as a result of state-level policy makers being deliberate about overturning ultra-punitive zero-tolerance discipline policies.

North Carolina is also one of few states that has made publicly available the disaggregated discipline data by race and gender. What has not changed however, is the very pronounced disproportionate representation of students of color. Black students in particular are as much as four-times as likely to receive a short-term suspension when compared with their white counterparts. This difference is particularly egregious among black females who are nearly six-times as likely as white girls to be suspended short-term. The patterns persist when looking at long-term suspensions as well.

What has to be asked is what is causing these racial gaps? To be clear, disproportionality does not necessarily mean discrimination. But if similarly situated students of different races are committing the same offenses and aren’t being treated equitably it does denote racial disparity and is cause for concern.

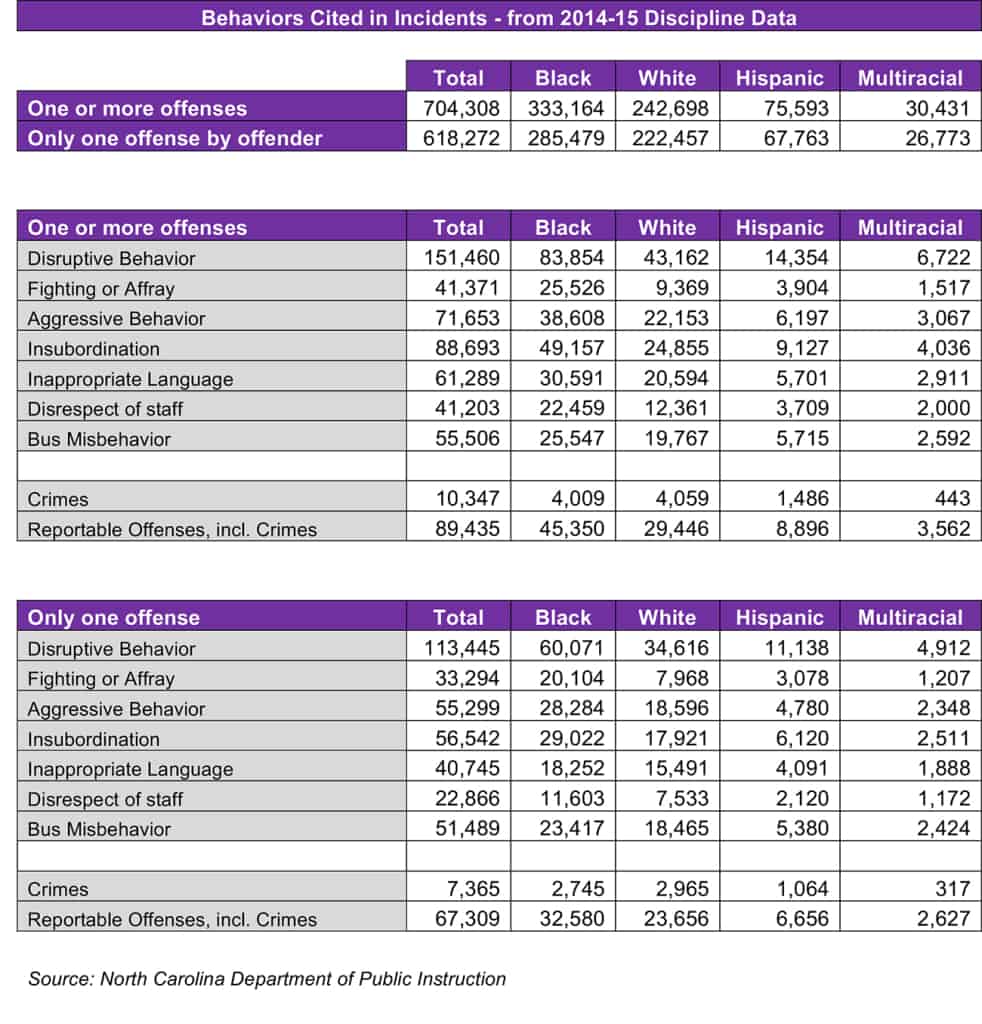

Some have hypothesized that the clear and obvious reason students of color are disproportionately disciplined must be because they commit higher rate of suspendable offenses. The differential behavior theory may seem logical on face value but doesn’t stack up when looking at the evidence. Fortunately, there has been a great deal of research around this very idea that disproves differential behavior as the driver of disproportionality.

In the study “The Color of Discipline: Sources of Racial and Gender Disproportionality in School Discipline”, researchers found that white students were more likely to be punished for objective offenses (e.g., vandalism, smoking). These are violations that warrant a particular disciplinary response according to policy. Black students, however, were more likely to be punished for offenses that require subjective interpretation (e.g., disrespect, excessive noise, threatening behavior). These are essentially judgment calls dependent on the teacher or administrator.

This is certainly corroborated by the NCDPI data where white first-time offenders are suspended more for reportable crimes, while black first-time offenders are suspended more for disruptive behavior, aggressive behavior, insubordination, inappropriate language, disrespect to staff, and fighting and affray.

These again are mostly discretionary categories left to interpretation, and leaving plenty of room for implicit racial bias to play a role. This deals less with intentional mistreatment, but rather subconscious attitudes and judgments toward particular racial groups. In short, it is perfectly plausible for stigmas around race to influence the treatment of students, even if the people or policies themselves are not overtly racist.

Perhaps what is most dangerous about the lingering discipline disparities is their part in what scholars have coined the School-to-Prison Pipeline. This phenomenon describes the relationship between push-out factors such as exclusionary discipline and encounters with the criminal justice system — usually ending in prison. Students who are suspended are less-likely to graduate and more likely to be truant, putting them at increased risk of delinquent behavior. The pipeline in North Carolina is particularly accelerated because we treat youth over the age of 15 as adults once they come into the criminal justice system. The destructive cycle tends to have a disparate impact on the students of color, as they are the subgroups overrepresented in the discipline data as well as correctional facilities. All of this contributes to the unyielding racial achievement gap — the difference in academic performance between minority and white students — and part of a larger system of disadvantage.

In the Public School Forum’s Top Ten Issues in Education published earlier this year, we listed number four as “Elevating Race as a Focal Point of Public Education.” This was done because race continues to be a significant factor in the educational outcomes of students. Given the sensitivity of the topic, our complex history and politically contentious environment it would be easier to sidestep the issue altogether. However, this would prove a disservice to far too many students in our state and default on our commitment to equal educational opportunity for all children.

As such we have spent the better part of the past six months conducting our bi-annual Study Group XVI focusing on educational opportunities. One of the three focus areas selected for the study is racial equity. After reviewing literature, meeting with subject-matter experts and conducting work sessions with stakeholders, the Forum is poised to release its final report offering policy and programmatic recommendations. The issue of discipline disparities has been explicitly identified as one of the subtopics of racial equity and will be included in the document.

As an educator, I know full-well the pressures and demands of this most noble profession. As State Teacher of the Year, I worked hard to defend the dignity of the work and represent the 95,000+ teachers of North Carolina. While some have suggested focusing on racial disparities would cause anxieties and dissonance in a majority white workforce, our ultimate allegiance must be to the children who populate our schools all over the state. We ought not disregard a negative phenomenon impacting students like discipline disparities to preserve the sensitivities of the adults who serve them. The center of the educational universe is the children. A teacher’s proximity to them is the only thing that gives the profession any importance or luster. Those responsible for that power must be reflective in assessing how their work impacts all students — positively or negatively.