This is part 5 of a five-part series documenting the history of the Winton Triangle community and the C.S. Brown School. It’s a story about the struggles that befell a pioneering community and the values that survive all these centuries later to sustain hope for the future. Read the rest of the series here.

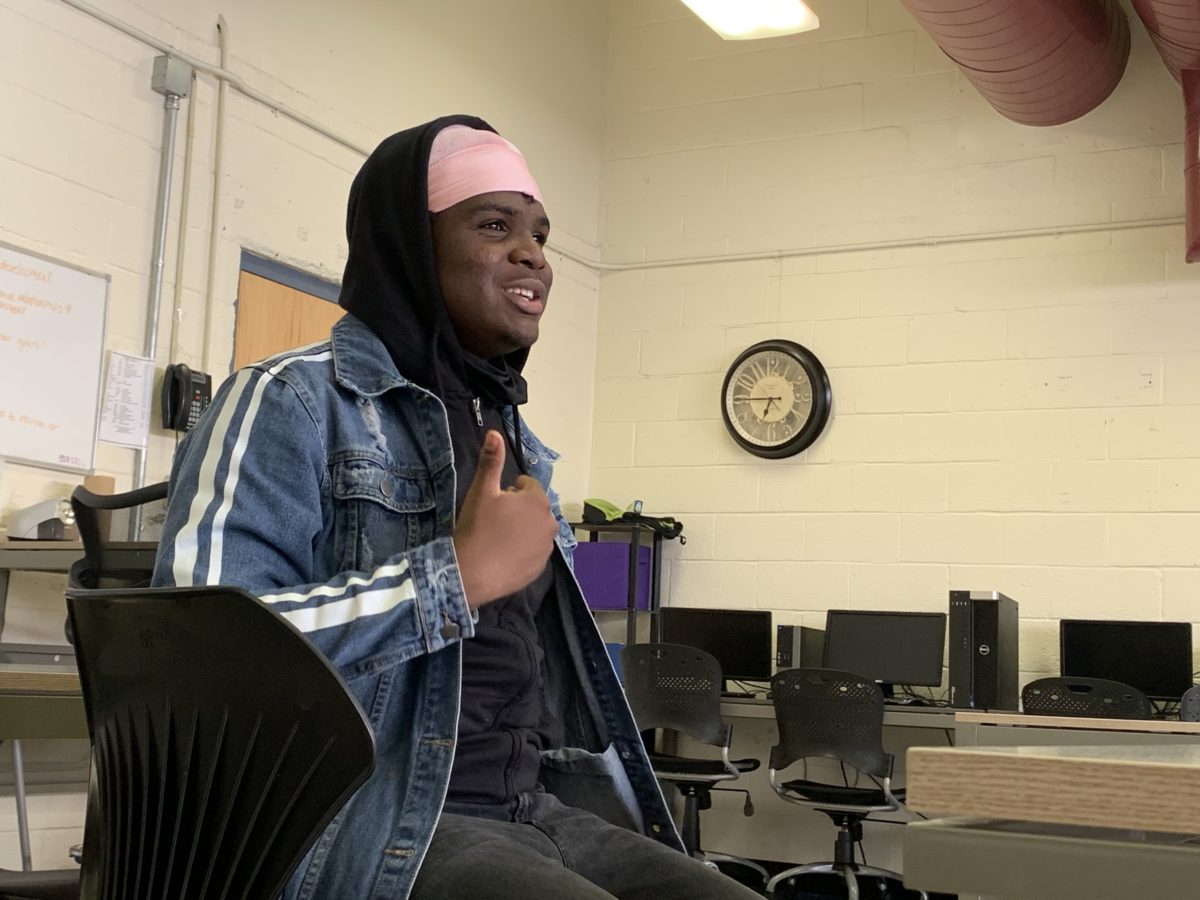

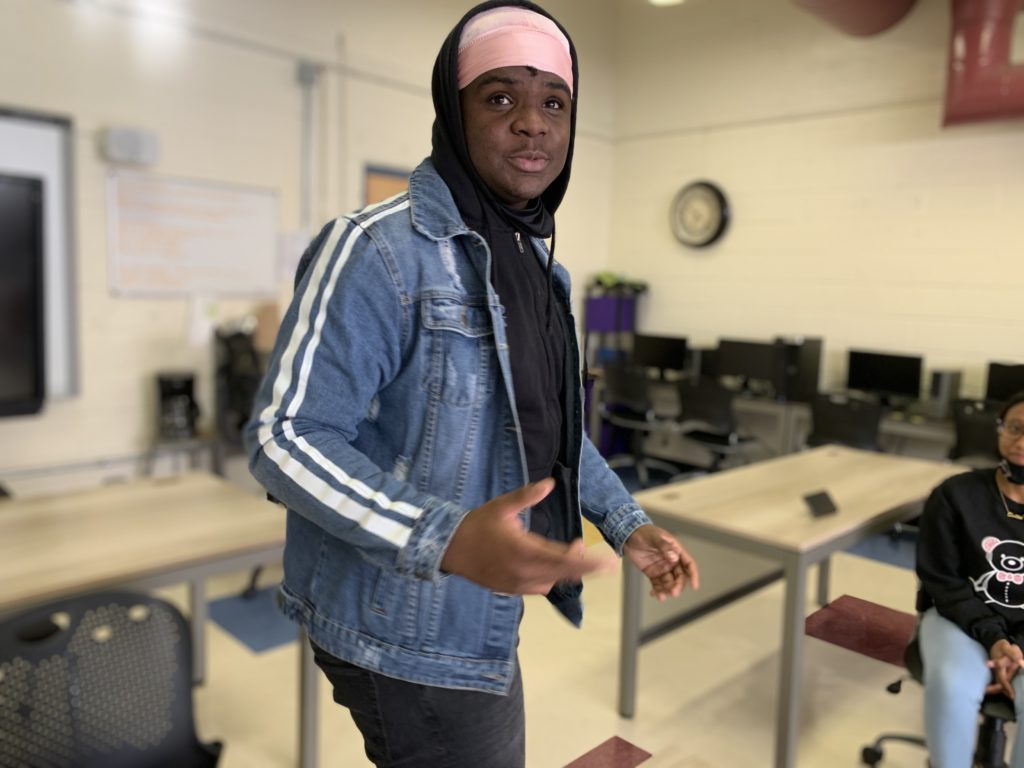

Kenton Valentine needed a place like C.S. Brown. He wasn’t familiar with the relationship-building approach of its principal and teachers, but he knew deep down that it represented a way out of his condition, a way out of Ahoskie and Winton. And he desperately wanted that.

That’s why his heart stopped when, days before his interview for the application-based school, his middle school suspended him for fighting.

Kenton’s is a story about what can happen when a school prioritizes building relationships and addressing trauma. And there are several stories like Kenton’s at C.S. Brown High School STEM, which insists on getting to know its students and offering help and accommodations rather than focusing first on discipline.

“My theory here is, you have to reach them to teach them,” said Daphne Lee, business teacher at C.S. Brown. “First you reach them. You have to talk to them, know them — so that you know if something’s wrong. Then you can teach them, because now you know what they need. That’s the culture that we spread here. I think it comes from within, as a teacher and as a person.”

Kenton is grateful for the culture. He calls C.S. Brown a family. A family, he says, he thought he’d miss out on.

A family doesn’t blindly punish. It looks first for ways to help.

When Kenton got his first and only suspension, he was sure it meant the end of his dream of attending C.S. Brown. But when he went in for his interview, he was given an opportunity to talk about what happened.

A boy in school had been picking on his little cousin. Kenton asked the boy repeatedly to leave his cousin alone. All that did, Kenton said, was provoke the boy into picking on him, too.

“I continued and continued to tell the principal, to let them know they need to stop this before something happens,” Kenton said. But nothing came of it.

One day, Kenton said, he was riding the bus and this other boy was there. The boy kept messing with Kenton. Kenton ignored it for some time, but after a while he couldn’t control himself.

“He kept picking and kept picking and kept picking,” Kenton said, “and I just spazzed and we ended up fighting.”

Kenton was automatically suspended for 10 days.

“I felt like when I got suspended, everything had went down the drain that I worked for to get to this school,” he said.

But he was wrong.

“We gave him an opportunity,” Jones said. “I’ll tell you, something happens when a kid knows you care about them. And they know the difference between fake love and real love. They’ll tear you all to pieces if you got fake love. But when you’re willing to hear them out and understand what they’re coming from, that makes all the difference.”

Kenton was no dummy. He just needed someone to root for him.

“And, forever, I will be grateful because they still took a chance on me,” he said.

It has meant a world of difference for him. Kenton is consistently on the A/B honor roll. He’s a lively presence in class. He has college plans. He said he isn’t sure he could have done that elsewhere.

Marcus Lewter and Caitlin Saunders have similar stories of developing relationships with educators at C.S. Brown.

Caitlin said it’s easy to talk with most teachers when she’s feeling overwhelmed, whether because of assignment deadlines overlapping or things happening outside of school. Her experience is that the teacher will talk it through with her and look for ways to reduce her stress.

“It’s like a family here,” Caitlin said. “I definitely believe they care about me as more than just a student.”

Marcus said he felt comfortable opening up to a lot of his teachers — especially Lee. He would talk to her when things outside of school were bothering him, and she would take the time to listen and advise. He has her cell phone number and uses it.

“We can talk to her about anything, and it all helps you do better in school because if you’re worried about something outside of school it’s going to still affect your school work,” he said.

The difference between taking an interest and just pushing kids through

For Lee, the mission is personal.

She had two experiences with Hertford County Public Schools that helped shape her approach to teaching. The first was with her daughter, who was in the second grade when she moved from New York to Ahoskie.

Her daughter was used to a little faster-paced instruction and was getting bored, she said. When she would get bored, she would do other things.

“Oh, she talks too much,” they would tell Lee. Lee didn’t argue with them about the instruction, but she wanted her child’s sense of self left unharmed.

“Well, you know, that’s her,” she would say. “That’s her personality. Don’t crush it. Don’t kill that personality, because one day that’s going to help her be who she is.”

As a parent, Lee wanted her daughter, who grew up to become a doctor, to be seen as a whole person — celebrated for her strengths and encouraged.

That was the experience she had with her son. He was sometimes overactive in class. An assistant principal noticed his trouble focusing and developed a relationship with him. He realized that Lee’s son was worried about graduating and came up with a plan to keep her son motivated.

“He made my son a diploma,” she said. “And he told him, ‘This is temporary.’ Every day when my son came in, he would show it to him and say, ‘You will graduate.’ And all the other principals were like, ‘Oh, he’s not gonna make it.’ But every day he showed him that. And we got right to the end and he looked at my son and said, ‘I told you. I knew you could do it.'”

Lee said those experiences had a profound impact on her teaching style.

“That’s the difference between someone taking interest and somebody just pushing you through,” she said. “I’m going to take an interest in my students.”

At C.S. Brown, educating the whole child is in its roots

School doesn’t always look conventional there, but that’s the C.S. Brown way. Getting to know the whole story behind student behavior means you can make changes to help with underlying issues.

Lee has been known to call students who can’t make it into class — either because they’re sick or their parents need them at home — and she’ll put them on speaker so they can hear the lesson. Other teachers will shift deadlines or spend extra time with students before and after class.

The whole-child approach is fundamental to the school’s culture, Jones said. And it’s consistent with the community’s culture, Dudley Flood said.

“That term ‘whole child,’ that wasn’t just a euphemism to us,” said Flood, who grew up in Winton and later led the state’s efforts to desegregate schools in the 1970s. “That was significant and important to me. And it still is to this very day.”

When the Chowan Education Association established the school now known as C.S. Brown in 1886, it was for the advancement of education for Black youth. Marvin Tupper Jones, a historian of the area, said that for the school’s namesake, Calvin Scott Brown, the mission extended beyond that. Brown was the leader of several churches and brought his pastor’s philosophies with him, Jones said.

“So serving the emotional needs of the students and developing values, that was always important at that school,” Jones said.

It shows up in the next generation of graduates.

Kenton recently had the opportunity to visit with the Boys & Girls Club of Edenton and make each child there a personalized jean jacket, which he sells as part of a business he started.

“They were just so excited,” he said. “And I kept thinking, why don’t we have this in Ahoskie? I should be able to do this in Winton.”

Marcus and Caitlin started their own businesses, too, and they talk about giving back to the community if their businesses take off.

Folks who grew up in Winton many years earlier are pleased to hear how the community’s values and its centuries-long heritage of pride and self-sufficiency are preserved in the school.

“It’s encouraging,” said Michael Perry, who was born in Winton in the 1960s and later became the school district’s superintendent. “It’s how it always was. You were just encouraged to come back. That was one of the things that was always taught, that you want to come back and make a difference in your community.”

In that regard, Jones counts the work of the district and his teachers a success. Yes, the small school is achieving academic excellence, but preservation of the spirit of the past is the real success.

“That’s the goal: Give everybody a dream,” Jones said. “That’s why this school was built, to build dreams. And we honor that.”