Share this story

- Periodic reappraisals of how best to govern public higher education are not uncommon, especially for North Carolina's system of community college. Read to learn more about what governance in higher education entails.

- The first article in this two-part series provides context for public deliberation and begins by explaining the meaning of “governance” in the context of higher education and then looks at the development of the current governance model for the NCCCS.

|

|

Highlights

- The North Carolina Community College System is the result of decades of evolution.

- Amid current conversations about consolidation and a recent proposal to overhaul how the community college system is governed, it’s important to understand how we got here.

- “Governance” refers to the system that guides everything from oversight and funding to admissions standards and curriculum.

- The system current governance structure — a state board that oversees local boards at all 58 colleges — emerged in response to economic needs following World War II and has remained largely the same ever since.

Part I

In 1962, the Governor’s Commission on Education Beyond the High School, a 25-member panel named by Gov. Terry Sanford, recommended the creation of “one system of public two-year post-high school institutions offering college parallel, technical-vocational-terminal, and adult education instruction tailored to area needs; and that the comprehensive community colleges so created be subject to state-level supervision by one agency.”1

While every commissioner supported the proposal, they differed over how to govern the new system, given concerns about which entity should supervise it, how to balance institutional and public interests, and what the relationship to public universities should be. 2

Based on the commission’s report, the N.C. General Assembly established in 1963 what is now the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS), a network of 58 institutions that enrolled 574,000 students in 2021-2022. 3 Over its 60-year history, NCCCS has grown in size and complexity, yet it has never quite outgrown the original questions about how best to govern it.

In late 2021, The Assembly reported on possible legislative interest in folding community college governance into the university system. 4 Last week, Senate Bill 692, titled “Community College Governance,” was filed in the General Assembly. A draft version of the bill outlines the following goals: “to clarify the authority of the president of the community college system, to make changes to the appointments to the State Board of Community Colleges and local boards of trustees, and to make technical changes to statutes governing community colleges.” Clearly, questions of governance structures in the community college system remain top-of-mind within North Carolina’s legislature.

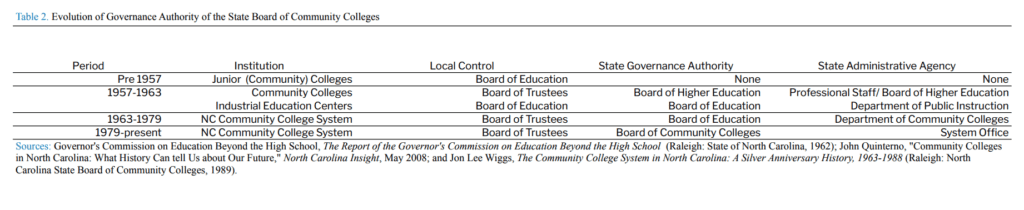

Periodic reappraisals of how best to govern public higher education are not uncommon. Models suited for a state at one moment in history or under one set of socioeconomic conditions might prove inappropriate for another. When the legislature placed the new community college system under the State Board of Education in 1963, it was responding to that era’s realities. When conditions later changed, the legislature voted in 1979 to shift authority to a new State Board of Community Colleges, where it remains today. 5

Redesigns of governance models can be politically fraught and too narrowly focused on structural and bureaucratic issues. Easily lost is the overarching goal of student success. Higher education governance and the associated planning, budgeting, data management, regulatory, and administrative functions exist not as ends in themselves, but as means for helping students access, persist in, and complete programs in a timely and affordable manner. Any changes should be mindful of the system’s mission and history.

To provide context for public deliberation, this article begins by explaining the meaning of “governance” in the context of higher education and then looks at the development of the current governance model. Part II of this series compares that model to those used in other states, paying particular attention to the distinctive nature of community colleges.

What is “governance” in higher education?

State governments assumed primary responsibility for postsecondary education following the Second World War. Today, North Carolina alone has 58 public two-year community colleges, the second highest in the country, and 16 four-year universities. 6

Writing in 1947, the Commission on Higher Education, a body named by President Harry Truman, called for a major expansion of higher education in response to the increasing scientific and technical training needed for economic growth, the deepening integration of the United States into the global economy, the growing size and diversity of the population, and the need to eliminate racial barriers that denied opportunities to African Americans. 7 The commission argued that absent an expansion, the nation’s economic and civic vitality would erode. 8 To achieve these goals, the commission called on states to build community college systems that collaborated closely with public schools and universities. 9

Virtually every state answered the commission’s call and expanded their educational systems by the early 1970s. Increased state investment benefited individual institutions while raising questions about appropriate boundaries. As the principal funder, state governments had an interest in ensuring the proper use of public funds for the achievement of public goals. Yet, individual schools and their internal stakeholders reasonably worried that state officials might politicize higher education or try to substitute their judgement for those of educators in fundamental areas like course content, classroom pedagogy, and scholarship.

Researcher Robert Berdahl described that tension as one between “substantive” and “procedural” autonomy. 10 “Substantive autonomy” refers to such internal institutional decisions as admissions standards, faculty recruitment and promotion, and course content. Perhaps in an ideal world, each educational institution would govern itself as it sees fit, but in reality, all institutions are subject to legal, regulatory, and financial constraints imposed by the state. “Procedural autonomy” refers to state-imposed restrictions like the appropriation of funds, the use of accountability measures, and the approvals needed to add a program of study.

Particularly for public institutions, the overriding question is “not whether there will be interference by the state but rather whether the inevitable interference will be confined to the proper topics and expressed through a suitably sensitive mechanism.”11 That “suitably sensitive mechanism” is the governance model, which is a structure for mediating between the institutional concerns of individual schools and the concerns of elected officials and the broader public. Furthermore, a governance model relates to a given state’s particular “method of statewide coordination for all higher education policy and planning.”12

There exists, of course, no one “suitably sensitive mechanism” for governing public higher education, but most states have established some body or bodies to operate in a space between a state’s political leadership and its individual colleges and universities. Some entities have formal governing powers, others merely advisory ones. Some bodies are responsible for two-year and four-year institutions, others for just one of the two. Some organizations are controlled by the institutions or their voluntary associations, others by the public. And states can alter these bodies, their powers, and their responsibilities as they see fit.

Discussions of governance models typically focus on organizational structures. An alternative view is to look beyond the boxes on an organizational chart and consider instead how responsibility for core functions is allocated among central governing bodies, statewide administrative offices, and local institutions.

Scholar Aims McGuinness has identified the six core functions essential to the administration of higher education as the following:

- State-level planning.

- State finance policy, budgeting, and resource allocation.

- Data maintenance and information generation.

- Institutional and academic regulation.

- Administration of state-level services like student aid.

- Governance of systems and institutions.

Seen through this lens, governance involves the distribution of functions among various system stakeholders. 13

How did North Carolina’s community college governance model develop?

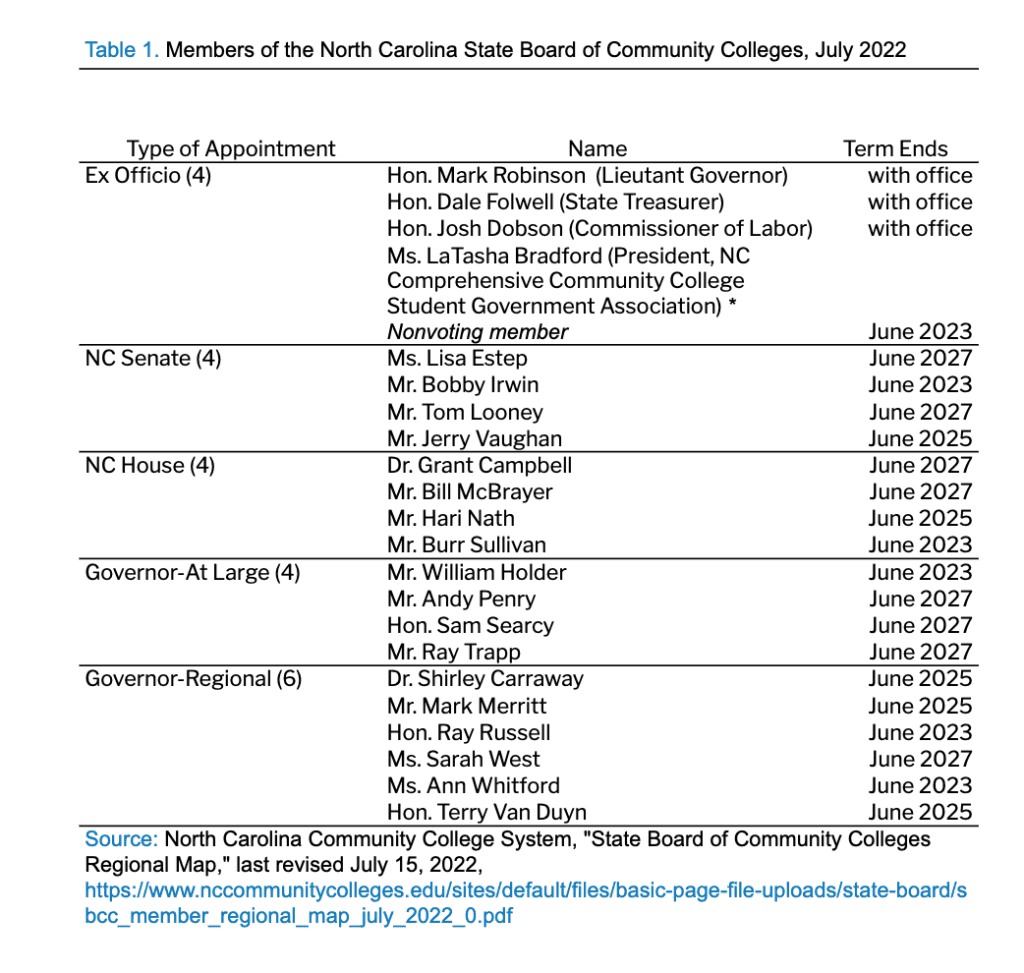

Since 1981, governing authority for NCCCS has rested with the State Board of Community Colleges, a 22-member body — of whom only 21 members vote — comprised primarily of persons appointed by the governor and legislature. 14

The Board relies on a professional system office led by a president elected by the Board to administer its policies and programs. 15 Each college is overseen by a local board of trustees, with an average 13 members named by the governor, county commissions, and local board of educations. These trustees select the college’s president, who oversee daily affairs. 16 This somewhat complicated model is a byproduct of the historical evolution of the NCCCS.

Two types of postsecondary institutions, two models of governance

When the General Assembly created the NCCCS in 1963, it was not painting on a blank canvas. It was aiming to merge two distinct systems of postsecondary education and training with different governance models into a rational whole that could expand over time.

North Carolina’s first community college, known as “junior”colleges at the time, was Buncombe Junior College, established by the local board of education in 1927 to provide tuition-free college transfer courses and vocational training. 17

A legal challenge questioning the local board of education’s authority arose, but the N.C. Supreme Court ruled in 1930 that public school districts could operate junior colleges. No other colleges were founded until 1947, when New Hanover County established Wilmington Junior College. Mecklenburg County then created Charlotte College in 1949 and Carver College (later Mecklenburg College), an institution serving African-American students, in 1950.

Governing authority for the first colleges rested with local entities like boards of education, with the state government playing little role. Operating funds came from local taxes and tuition, and local governments also paid capital costs. Perhaps owing to their links to the public schools, the colleges gradually came to favor academic instruction over vocational and adult education. 18

During the 1950s, state leaders recognized that long-term economic growth required workers with more advanced skills, particularly vocational skills, than was common before the Second World War.

Some leaders favored the Truman commission’s vision of the single comprehensive community college that would “attempt to meet the total post-high school needs of its community” by offering vocational and adult education along with college parallel courses. 19 Others, including Gov. Luther Hodges in North Carolina, favored a “dual approach” in which one set of institutions would offer college parallel education, and another set would offer vocational and adult education. 20

The state legislature responded in two ways. First, the General Assembly passed the Community College Act of 1957, under which the state assumed control over the existing junior colleges. In exchange for expanded state support, colleges were required to sever ties to local school boards and establish individual boards of trustees to govern them. State-level oversight would rest with the Board of Higher Education, a nine-person statewide coordinating body established in 1955 to facilitate comprehensive planning of postsecondary education. Furthermore, the colleges were to focus primarily on college parallel instruction. The act also created a process for founding new schools, which led to the birth of the College of the Albemarle in 1960 and Gaston College in 1962.

Second, the General Assembly authorized a network of industrial education centers in 1957 to offer industry-responsive training programs, ranging “from short upgrading courses for particular groups of industrial employees to two-year programs for the training of technicians.”21 Seven centers launched in 1958, with 11 others receiving authorization pending future funding. 22 Governance for each center rested with the local board of education and its district superintendent. At the state level, the Board of Education provided oversight with administration functions performed by the Department of Public Instruction (DPI). 23 Financial responsibilities were split between local governments, which were to fund the physical facilities, and the state, which agreed to underwrite operating and equipment costs.

Creating one comprehensive system of community colleges

By the early 1960s, North Carolina operated two different educational systems in the space between the public schools and the four-year universities. Six junior colleges offered the equivalent of the first two years of undergraduate instruction under the supervision of local boards of trustees and the Board of Higher Education. Meanwhile, 15 industrial education centers (with five more under construction) offered vocational, technical, and adult education instruction under the direction of local school boards and the State Board of Education. 24

Every component of the state’s educational system was expanding rapidly. The demographic surge known as the “Baby Boom” was boosting the number of children entering public schools. The combination of a larger population, improving high school graduation rates, generous financial support, and the heightened need for postsecondary education to prosper in a changing world was fueling enrollment surges in colleges and universities. Meanwhile, political tensions between and among the three universities that constituted what was then known as the Consolidated University of North Carolina (which today includes UNC-Chapel Hill, NC State University, and UNC-Greensboro) and the nine public senior colleges (including what is now UNC-Pembroke and NC Central University) were complicating efforts to address changing realities in a coordinated manner. 25

When it came to postsecondary education, uncoordinated growth impeded rational planning, efficient use of public funds, and non-duplication of programs. The General Assembly attempted to tackle the problem in 1955 by creating the Board of Higher Education. Perhaps because its powers were arguably advisory, the Board struggled — or was perceived to struggle — in coordinating the universities, senior colleges, and community colleges under its purview. 26

Concerns about the status quo led then-Gov. Terry Sanford to appoint a 25-member Governor’s Commission on Education Beyond the High School in 1961. The commission prepared a comprehensive plan for overhauling postsecondary education, with special attention paid to the community colleges and industrial education centers. The core recommendation was to merge the two into a single system of comprehensive community colleges offering college transfer, vocational, and adult education on an “open door” basis. Funding would come from state appropriations, local support, and tuition. Specifically, the state would fund most operating and equipment costs, while local governments would support physical facilities.

The proposed governance model for this new system was an amalgam of the existing ones. Like the community colleges, each school would have a local board of trustees, but as with the industrial education centers, state oversight would rest with the Board of Education, rather than the Board of Higher Education. This was because the colleges otherwise would be ineligible for federal vocational funding. 27 The Board of Education would receive input from a newly appointed advisory council and administer its programs and policies via a new professionally staffed Department of Community Colleges. 28 Ultimately, this framework became the basis of the Omnibus Higher Education Act of 1963, which created the North Carolina Community College System.

The question of higher education governance divided the members of Gov. Sanford’s commission. While they unanimously supported creating a unified community college system, a six-member minority objected to the proposed reforms to the Board of Higher Education.

Practically, the transfer of the community colleges to the Board of Education would cut against coordinated planning for the entirety of public postsecondary education, while the proposed structural changes to the Board would grant too much power to individual institutions at the expense of the public interest. 29 Political opposition to the suggested reforms to the Board of Higher Education resulted in legislative action being deferred until 1971, when the Board was replaced by a new UNC Board of Governors responsible for the restructured 16-campus UNC System. 30

Establishing a dedicated State Board of Community Colleges

The NCCCS grew rapidly between 1964 and 1979, a period during which “the system evolved from a collection of industrial education centers and junior colleges into a federation of 58 quasi-independent colleges.” 31

Swift growth, combined with growing pains and administrative and financial challenges, raised concerns among some legislators. During the 1970s, the legislature repeatedly debated whether NCCCS governance should stay with the Board of Education or be transferred to either the UNC Board of Governors or an independent board. 32 The idea sparked opposition from the Board of Education, editorial writers, and various officials. Critics feared changes would weaken the NCCCS by shifting too much authority to local colleges, resulting in a devaluation of vocational education, a degradation of college programs, and an increase in competition for students with private colleges.

The General Assembly ultimately voted in 1979 to establish the State Board of Community Colleges (SBCC). A transition committee chaired by Gov. Sanford oversaw the reassignment of functions away from the State Board of Education. 33

The SBCC first met in late 1980 and assumed full control in January 1981, and the structure remains in place today. 34

The State Board of Community Colleges in 2023

Of the 18 appointed members of the State Board of Community Colleges’ 22 members, 10 are appointed by the governor, four by the state Senate, and four by the House of Representatives to four-year terms, with a limit of two consecutive terms. 35 The lieutenant governor, state treasurer, commissioner of labor, and president of the North Carolina Comprehensive Community College Student Government Association all serve ex officio, but the student member has no vote. To administer programs and policies, the SBCC relies on a professionally staffed system office that is based in Raleigh and overseen by a system president chosen by the SBCC. 36

While governing authority for each individual college resides with the local board of trustees, the SBCC is broadly empowered by statute to “adopt and execute such policies, regulations, and standards concerning the establishment, administration, and operation of institutions as the State Board may deem necessary to ensure the quality of educational programs, to promote the systematic meeting of educational needs of the State, and to provide for the equitable distribution of State and federal funds to the several institutions.”37

The SBCC approves and allocates college budgets; authorizes capital projects; approves the hiring of college presidents; establishes and administers standards for professional personnel, curricula, admissions, and graduation; sets and regulates accounting procedures; and defines tuition waivers. 38 Recognize, however, that the powers enjoyed by the local boards result in the SBCC exercising less direct authority over each college than the UNC Board of Governors exercises over each university. 39

The State Board of Community Colleges remains independent of the UNC Board of Governors and the State Board of Education, yet the three entities often collaborate for practical and legal reasons (such as defining college articulation agreements, or operating dual enrollment programs). Also, the NCCCS president sits in the Education Cabinet, a statutorily created body chaired by the governor and tasked to resolve differences and “develop a strategic design for a continuum of education programs.”40

Part II of this series compares this model to those used in other states, paying particular attention to the distinctive nature of community colleges.