Research indicates that the teacher is the most important factor in a student’s success, and the most important factor in a teacher’s success is likely the principal. Over the last five years, a lot has happened for principals in North Carolina — from changes in the level of funding and structure of principal pay to a bolstering of the preparation systems for these school administrators. The story of principals tracks closely with the evolution of EducationNC. Our first story was on principal pay, and we have revisited the subject again and again.

Problems with principal pay schedule

On Jan. 8, 2015, we wrote about Katie McMillan. She had become principal of Centennial Campus Magnet Middle School in Raleigh in 2014. What she didn’t realize when she became principal was that, according to the principal salary schedule in existence back then, she wasn’t scheduled for a step increase until 2019. And she wasn’t the only one who would be waiting years for a pay bump.

McMillan was a principal who oversaw between 44 and 54 teachers, which was one of the categories on the principal pay schedule. For those principals, they got the exact same level of pay on the pay schedule from year 0-19. Now, most principals don’t start out with zero years of experience. McMillan had 15 combined years of experience between being a teacher and a principal. But still, no pay increase until year 20 was an odd thing to see.

This was a problem that ran through the various categories in the principal pay schedule, and it was only one of them. The principal pay schedule was out of sync with the teacher pay schedule, so in some cases, teachers made more than the principals who oversaw them. And often, the only way for principals to actually see increases in pay was to leave their school or district. That causes a problem of stability for schools, and could be particularly detrimental to low-performing schools trying to find a way to turn around.

Perhaps even worse than all of this was the fact that North Carolina was 50th out of the 50 states and Washington D.C., for principal pay. Almost dead last.

There was some movement to do something about principals and principal pay in those early days, but it didn’t get much traction. As early as March 2015, Sen. Jerry Tillman, R-Randolph, was talking about scrapping the principal pay schedule and just giving bulk funds to districts to pay principals what they wanted.

There was little momentum to really tackle the problems with the principal pay schedule, however. In January of 2016, a A House Select Committee on Education Strategy and Practices convened to talk about educator compensation. During it, a group of superintendents heard about the problems with the principal pay schedule. After the presentation, they went on to talk mostly about teacher pay.

The conversation continued in November of that year at a Joint Legislative Study Committee on School-Based Administrator Pay. There, Tillman again talked about his idea to scrap the principal pay schedule and replace it with funds sent directly to districts to use as they see fit. That was a plan that got a lot of pushback at the meeting. Again, it was a plan that went nowhere.

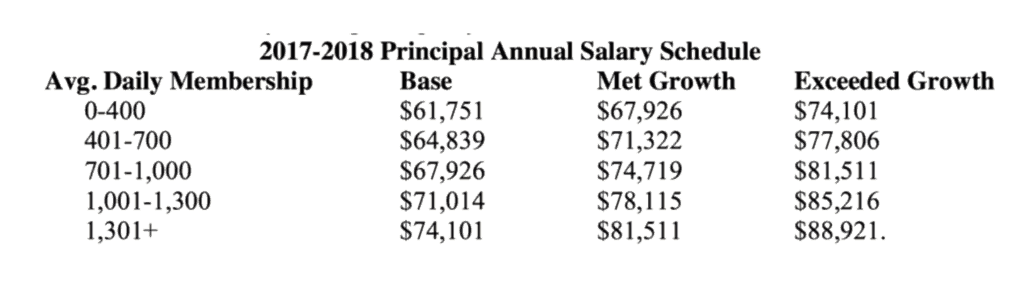

It wasn’t until the long session in 2017 that lawmakers finally started to tackle the principal pay schedule in earnest. The budget passed that year gave principals an average 8.6% salary increase over two years and assistant principals a 13.4% average salary increase over the biennium. Perhaps more significantly, it redid the principal pay schedule. It simplified it, taking away years of experience and just using school size and the school’s academic growth score to determine compensation.

Problem solved, right? Nope.

Criticisms of the new plan emerged pretty quickly.

While many principals received pay raises under the new schedule, some — the ones at the top of the food chain — didn’t. They would actually receive less except that a hold harmless provision in legislation said that they would continue to make what they made before if they stood to take a pay cut under the new schedule. That hold harmless provision wasn’t indefinite, however. Every legislative session since, lawmakers have had to extend the hold harmless to ensure that more senior principals don’t lose pay.

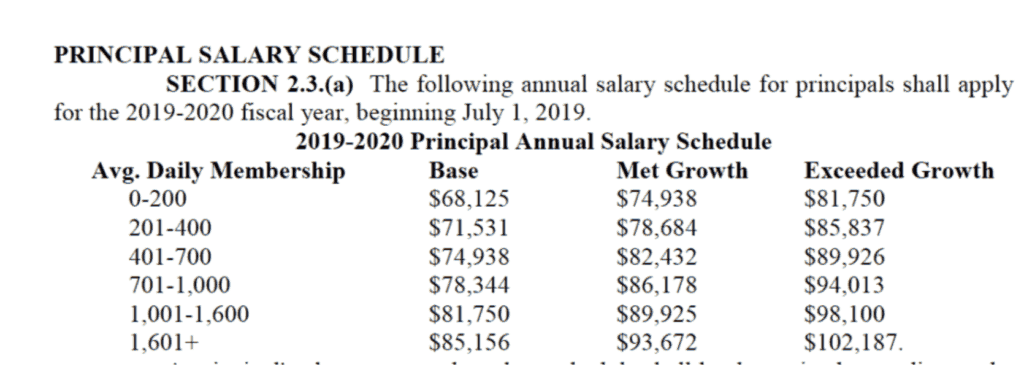

Another criticism was that the new principal pay schedule encouraged principals to work at schools with high academic growth. Basically, a principal got a base salary based on the size of his or her school. Then he or she got a little more money if the school met academic growth. And the principal got even more if the school exceeded academic growth. Critics worried that this would discourage principals from working at low-performing schools, often the ones most in need of strong leadership but least likely to achieve stellar growth.

Also, years of experience had been taken out of the calculation of principal pay, and there were some principal advocates who wanted to see that returned as part of the formula. The removal of longevity pay and extra pay for advanced degrees was also sharply debated.

In the 2019 long session, principal pay was increased, but the structure of the schedule still remains the same. The principal pay raise was an average 6.2% increase in pay for principals, providing $15 million extra in both years for the raises. The schedule was changed slightly, but the overall structure remained the same. Lawmakers also added up to $30,000 in supplements per year for principals willing to teach in low-performing schools.

At the end of 2019, WestEd, an independent consultant directed by Judge David Lee to come up with recommendations to meet the mandates of the Leandro case, dropped its report with recommendations on how to improve education in North Carolina. A section in the report addressed principal pay and explained some of the shortcomings of the current principal pay structure:

“A consequence of the new policy is that principals’ salaries now vary on the basis of their school’s size and performance from year to year. The compensation system creates a disincentive for effective principals to work in underperforming schools, which often take more than one year to improve and meet or exceed targets for growth.

“Compensation and benefits can be used to attract and retain effective principals in hard-to-staff and low-performing schools, yet there are no current bonuses or incentives for principals to lead these schools. Principals are also no longer eligible for advanced and doctoral degree salary supplements. In addition, principals (and other educators) hired after January 21, 2021, will not receive health benefits in retirement. These changes in policy make leading a small and low-performing school less attractive to aspiring principals.”

The report went on to say that in a survey of state principals, 24% said that principal pay could influence their decision to leave their role as principals in the next three years. Twenty-four percent said they would retire, try to become a principal at another school, or leave the role of principal because of the compensation system. Forty-four percent said they opposed or strongly opposed the system.

The short session of the General Assembly is coming in spring of this year, so we wait to see if lawmakers tackle these issues.

Preparing effective principals

The WestEd report also highlights the need for effective principal preparation, and calls out NELA — the Northeast Leadership Academy — by name. The program is housed at North Carolina State University and subsidizes tuition for higher degrees for potential principals, sets them up with internships, and gets buy-in from district superintendents ahead of time about potential candidates going through the program. It is now called the North Carolina Education Leadership Academy (NELA).

NELA, along with two other principal prep programs — The Sandhills Leadership Academy and Triangle Piedmont Leadership Academy — were able to thrive thanks to the federal Race to the Top Program.

In 2011, the Race to the Top began offering education grants around the country. NELA got funding for its second year through the program.

But when Race to the Top money began running out, neither Piedmont nor Sandhills could get funding to continue, so they shut their doors, leaving only NELA as the state’s standout principal prep program.

Things began to change, however, during the long session of 2015. That’s when the General Assembly created the Transforming Principal Preparation (TPP) grant program and assigned the North Carolina Alliance for School Leadership Development (NCASLD) with administering it. The General Assembly appropriated $1 million for principal preparation purposes in 2015. In 2016, the legislature gave an additional $3.5 million to the issue. That money is administered by the NCASLD, which is supposed to identify principal prep organizations in North Carolina that can create strong programs for training principals.

The WestEd report also shouts out the state’s principal fellows program, which launched in 1993. It provides scholarships to people seeking an MSA degree to become a school administrator in the state. They can pick from 11 MSA programs to attend. All the programs are within the UNC System.

According to the report, by 2015, 1,300 people had completed the program with a 90% graduation rate. The report said that these graduates are more likely to actually take an administrative position and stay in North Carolina Public Schools when compared to MSA graduates from UNC-System schools generally.

In 2019, Gov. Roy Cooper signed into law a bill that would merge the Transforming Principal Preparation Program with the Principal Fellows Program.

The state of principals in North Carolina

According to the WestEd report, “challenges remain” for ensuring high-quality principals in North Carolina.

“There has been a significant reduction in the numbers of candidates entering principal preparation programs over the past decade; many schools are led by inexperienced principals with fewer than three years of experience; and the current principal compensation structure may be a disincentive to becoming a principal, particularly for becoming a principal in a low-performing school,” the report states.

When I began covering education for EducationNC, principals were rarely talked about. Each General Assembly session since, they have become more and more a focus of the conversation. While compensation and preparation for principals will likely never get the kind of attention that it does for teachers, there is growing understanding about the importance of principals and the best ways to ensure effective administrators are put in schools around the state.

With the WestEd report dropping at the end of 2019 and dedicating a portion of its findings and recommendations to the issue of North Carolina principals, it is likely that the North Carolina will continue to place greater emphasis on principals. Whether the strategies and policies the state’s leaders choose to implement going forward are effective remains to be seen. But no more are teachers the only focus of the conversation.