This is the fifth article in a series on faculty pay at North Carolina’s community colleges. Click here to read the rest of the series.

“If we are going to have a world-class community college system and produce a world-class workforce, then we have to be competitive with salaries.” – Mark Poarch, president of Caldwell Community College & Technical Institute

North Carolina’s past progress in boosting the salaries of community college instructors has stalled in recent years. A review of SREB data, in fact, indicates that the state’s average full-time instructional salary paid has not even kept pace with inflation. If the annual average full-time salary logged in 2006-07 simply had maintained its buying power, holding all else equal, the 2017-18 average would have been 6% higher, totaling $52,490 instead of $49,549.1 The lack of salary growth over the past decade is forcing every college to confront three sets of challenges with the exact mix varying from one school to another.

Challenge 1: Instructor shortages

“We’re in a rural community, and as a result, recruiting people, particularly with really specialized skill sets, is a challenge,” said Pamela Senegal, president of PCC.2 “It is difficult in rural America, for example, to find someone to teach in the latest technology. That’s one of the areas we keep attempting to recruit for, and we keep having to put that position back out there.”

She continued: “The other challenge is that, when we are able to recruit, many of our faculty do not live in our service area, and that creates a lack of understanding of the context of the students and the community we serve because they don’t actually live here. The other piece is the salaries that are expected in some of those fields. I’m having to make tradeoffs in other areas, or I’m having to bring in people with potentially less experience and take a chance.”3

Different challenges appear in metropolitan areas. While Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College is located in a desirable, growing city, an instructor earning the college’s typical salary would need to spend close to 30% of that salary to afford the city’s typical rent.4 The situation is somewhat better in Durham, where the typical rent would consume roughly a quarter of the typical salary paid at Durham Technical Community College.5 Given the comparatively deeper labor market in places like Asheville and Durham, potential instructors—even those drawn to teaching—may simply be unwilling to leave jobs that pay salaries more commensurate with local living costs to work at a local college.

Low, stagnant pay also creates difficulties in retaining faculty members, especially those with skills valued in the private sector. Noted Walter Dalton, president of Isothermal Community College: “It’s harder to get people in our applied sciences and health-related programs. That’s where we are losing people. In the applied sciences, they can go into industry. In health-related fields, they can make more at the hospital than they can here. So, we have to try to use our dollars cost-effectively but hire qualified people that can appropriately teach our students and give them these 21st-century skills.”6

“We had a HVAC class scheduled with 25 students registered. The instructor received a better salary offer from a local HVAC company, so he left the college to take a position in the field. We had to postpone the start of the class for three months in order to give us time to find a qualified instructor, which delayed us being able to meet the needs of business and industry in a timely manner.” – Mark Poarch

A struggle to attract qualified instructors is not limited to applied sciences like mechatronics and healthcare fields like nursing; depending on the college, it also can be difficult to attract individuals qualified to teach in college transfer programs, particularly those covered by the Comprehensive Articulation Agreement between the community college and UNC systems. When a community college graduate with an associate in arts or an associate in science degree gains admission to a UNC school, the student enters knowing that all the covered courses that were successfully completed will substitute for the corresponding general education or pre-major course needed for a baccalaureate degree.7 This means a student who successfully passes “Principles of Biology” at a community college school can count that class for a UNC school’s version of “Biology 101.” As they are teaching the same course, community college instructors require skills and credentials comparable to those of their UNC counterparts.

Even when a college has an adequate number of qualified instructors, shortages can emerge if licensing or accreditation standards change. If an accreditation body were, for instance, to require a specific program to employ a certain number of full-time instructors with doctoral degrees instead of holders of a master’s degree, an affected school might suddenly find itself lacking the proper instructors and unable to hire people with the required credentials.

In conversation, Dale McInnis, president of Richmond Community College, offered two examples of this dynamic.8 First, McInnis noted how a change to the Comprehensive Articulation Agreement required ethics to be a transferable course, yet at the time, many schools, including his own, did not teach ethics. Meeting this requirement necessitated the hiring of the appropriate instructors.

Second, McInnis explained how North Carolina is phasing in a requirement that all paramedics hold at least a two-year degree. This has necessitated the establishment of a new academic program that must meet all of the applicable accreditation standards, including the hiring of adequate numbers of qualified instructors.

Challenge 2: Reliance on part-time instructors

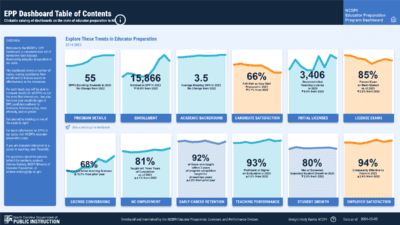

The number of part-time instructors teaching at North Carolina’s community colleges has risen steadily over the years. In 2017-18, the state’s community colleges employed 20,744 part-time, or adjunct, instructors, who accounted for 69% of the faculty corps.9

Part-time employment relationships can benefit individual colleges and their students. First, in applied fields, part-time relationships may enable people with private-sector expertise to bring their knowledge, experience, and networks to the classroom, resulting in more practical instruction and closer ties between a college and private industry. Second, part-time employment relationships provide management flexibility. Part-time positions are paid on an hourly basis, are rarely eligible for benefits, and are comparatively easy to add and subtract—all of which can help a college stretch its limited resources.

“We’re sometimes not able to fill those [instructional] positions, or it takes us such a long time for us to fill it, yet we still have a responsibility to teach these classes, so we probably are leaning more heavily on adjuncts,” observed Senegal.10 “And there is nothing wrong with that, particularly for continuing education. I think that actually is a good fit for continuing education because these are short-term things that are constantly changing, and so we really like having those folks who are doing this work currently also teaching for us.”

Yet an overreliance on part-time instructors can detract from the educational experiences offered to students. Adjuncts may only be on campus during scheduled class periods and are less likely to be available to answer questions or provide advice outside of class. Those who commute some distance also may be unaware of community needs or fully appreciate the backgrounds of their students. And since adjuncts often have other, primary jobs, their institutional loyalties may rest with their employer instead of the college.

“There is more reliance right now on part-time faculty and adjuncts than perhaps in the past, before the recession,” said President Dalton of Isothermal Community College.11 “It necessitated doing that to get through those tough times, but I would much rather have a full-time instructor fully invested in our college and our students.”

Despite that preference, Dalton recognized that financial pressures often drive the need for adjunct instructors. He elaborated: “In tough budget times and in order to find enough money to hire this person who needs to be a director, sometimes that dictates where we’re going to have to find a couple of part-time adjuncts to fund this full-time position because we’ve got to move the money to make that happen. That’s not optimum.”12

Senegal, meanwhile, reflected on some of classroom-level impacts tied to the use of adjuncts: “For some of these longer [curriculum] programs, for student success, it’s really better for students to be able to have access to someone who is full time, who is available to help them work through problems that they’re having, to give them extra tutoring and assistance, and that’s just not possible with adjuncts. I don’t ever want my adjuncts to feel like we don’t greatly value them because we certainly do. But there is a trade off in terms of student success.”13

Challenge 3: Internal faculty management

The latitude afforded to individual community colleges over the development of their faculty pay plans and in the allocation of salary funds enables them to stretch their limited resources as they see fit. Even with this flexibility, a college can encounter internal management challenges when overall pay fails to keep pace with the responsibilities assigned to instructors.

“The expectations of the faculty have evolved,” said Richmond Community College’s president, Dale McInnis.14 “There’s much more expectation for them to be engaged with their students and to be advising their students, not just academically but professionally. Connecting them with internships and prospective employers. Connecting them and preparing them for a successful transfer. I’m proud of what we’ve done here and the same work is happening across the state.”

Increased expectations, however, can spark problems when faculty pay fails to rise with added responsibilities. While colleges have some options for recognizing exemplary performance, such as awarding one-time performance bonuses, an inability to raise base salaries in response to new expectations eventually can lead instructors to leave for other employment or to retire earlier than they might otherwise—actions that may exacerbate a college’s staffing problems.15

“It seems like they [faculty] are always asked to do more and not be appropriately rewarded,” remarked Dalton.16 “The pay increases were non-existent during the Great Recession and have been fairly meager since. They [faculty] look out the window at where the economy is and I think a lot of them do wonder, ‘Maybe I should think of other positions. I love what I do, but I have to put food on the table for the family.’”

Even the ways in which a college uses its salary flexibility can have unintended consequences. If, say, a college uses its financial flexibility to systematically provide higher salaries to instructors in the applied sciences than to instructors in college transfer programs, it is free to do so. That choice may indeed be a logical response to local conditions, but it also can create internal pay inequities that may undercut faculty morale or cohesion while inadvertently introducing systematic pay inequities, as might occur when a class of higher paid instructors is overwhelmingly male while a class of lower paid instructors is predominately female.

“Our faculty choose to be in community college rather than in a K-12 or university setting. They know their work is critically important, and for many, it is a heart mission. I wish we could value them financially as we do educators in other settings. Community college is not ‘less than,’ but I feel like we send that message implicitly when our faculty aren’t paid equitably in comparison.” – Rachel Desmarais, president of Vance Granville Community College

What changes are possible?

In February 2020, the State Board of Community Colleges named as its highest budget priority for the upcoming “short” session of the General Assembly an increase in salaries of 5 percent for all faculty and staff employees—a proposal previously endorsed by the North Carolina Association of Community College Presidents.17 Even if the request survives the budget process and is granted, it will not, by itself, solve the longstanding issue of low pay for community college faculty. More comprehensive steps are needed at the statewide and institutional levels.

Legislative request: A 5% salary increase for 2020-21

As noted previously, the “mini-budgets” agreed to by the General Assembly and the governor during the ongoing budget impasse provided raises to state employees but not state-funded community college employees, including instructors, who were specifically excluded from the 2.5% salary increases granted to state employees in 2019-20 and 2020-21.18

The State Board’s request for a salary increase of 5% during fiscal year 2020-21 is an effort to “catch up” community colleges personnel to the raises granted to state employees this biennium. The estimated annual cost of that change is $62 million in recurring funds.19 Yet before the budget impasse began, the legislature already had identified as much as $48 million in funding for community college raises. Some $11 million was allocated in the base budget that was ratified but not enacted, while Senate Bill 354 (also ratified but not enacted) authorized $37 million for raises contingent on the original budget becoming law.20 Seen that way, the system’s request requires just $14 million in funds above those the legislature had agreed to provide.

Complicating the situation is that enrollment in the community system recently rose for the first time in a decade, resulting in an additional 8,600 full-time equivalent students. Fully funding that enrollment growth will require some $40 million, which, when combined with the salary increases and a small request to upgrade information technology, will bring the system’s total 2020-21 request for recurring funds to $107 million.21

Another complicating factor is that there is no guarantee that any additional salary money authorized by the General Assembly—either through raises or enrollment growth—will benefit any given instructor. Local colleges could use new funds for across-the-board raises, direct the funds to certain classes of instructors, or do something else entirely so long as they pay the minimum salaries in effect. Institutional discretion therefore could result in instructors at some colleges being treated better or worse than their peers at other institutions, just as some instructors within the same school might be treated better or worse than their co-workers.

Elements of long-term success: Statewide and local actions

While a 5% salary increase would be a positive development for North Carolina’s community colleges, such a raise, or even a series of small raises over a few years, would not propel average full-time pay to the top of the national rankings. There is a need for deeper reform on the part of state policymakers and the leaders of local colleges.

First, in the short term, the state could revise the funding formula that is the primary determinate of how much salary money each community college receives. Although the current model is deemed “functional and generally acceptable” by key stakeholders, shortcomings remain, particular in the areas of funding stability and adequacy.22 It also is unclear if the allotment values assigned to each funding tier reflect actual costs. If not, increases that bring the values closer to reality would expands the pool of resources available to pay salaries.

Second, both the community college system as a whole and individual campuses should consider strengthening their institutional capacities related to “strategic finance,” a higher education management approach that “encourages colleges to shift their thinking from spending and budget balancing to a ‘return on investment’ approach.”23 This involves looking at available resources more holistically, focusing on unit costs, and understanding the ties between student success and financial stability.24 In terms of faculty salaries, such a model could help ensure that available dollars are spent on the uses most apt to maximize student achievement. A challenge, however, would be ensuring that each college has the needed managerial capacities.

Third, individual colleges would benefit from looking to build internal pathways for pay progression, much as Wake Tech did when it established faculty ranks. Even if the funds are not available to provide large gradations in pay, the combination of a new title and a raise demonstrates to instructors that their work is valued, which can help with retainment.

Fourth, colleges might benefit from undertaking periodic pay equity studies so as to ensure that differences in faculty pay are rooted in objective, neutral criteria and are not biased, intentionally or not, against certain classes of instructors. Eliminating employee perceptions of unfair treatment is a powerful tool both for improving morale and cohesion and for reducing a common cause of workforce turnover.

Lastly, colleges could explore ways of “growing their own” faculty from individuals within their orbit. PCC, for instance, already helps existing staff employees develop the skills and earn the certifications needed to move into positions in such departments as information technology, and the college is exploring similar models for the development of instructors.25 The tradeoff in any such model is the risk that a supported employee may be “poached” by another employer, yet the investment made in the person combined with their community ties may bond them more closely to the college.

Conclusion

North Carolina long has struggled to compensate its community college instructors adequately. Despite progress in raising salary levels closer to regional and national averages during the 1990s and early 2000s, multiple factors have precluded any additional progress over the last decade. Every college in the state therefore is dealing, albeit in different ways, with such challenges as an inability to attract and retain qualified instructors, a growing reliance on part-time faculty, and an increasingly complex set of internal management dynamics. A boost in salaries, such as the 5% raise recently endorsed by various stakeholders, would help, but one-off measures alone will not alter the state’s current trajectory. Instead, deeper reforms are needed if North Carolina’s community colleges are to attract and retain the educators vital to the achievement of their educational and economic missions—missions just as essential to North Carolina’s future today as when the community college system was founded.