On our trip to Mexico, 42 teachers from North Carolina are learning and thinking about water and water policy in our state, in Mexico, and around the world.

Water issues are the same for most people and governments:

- Water quantity – do we have enough water;

- Water quality – is our water safe to drink;

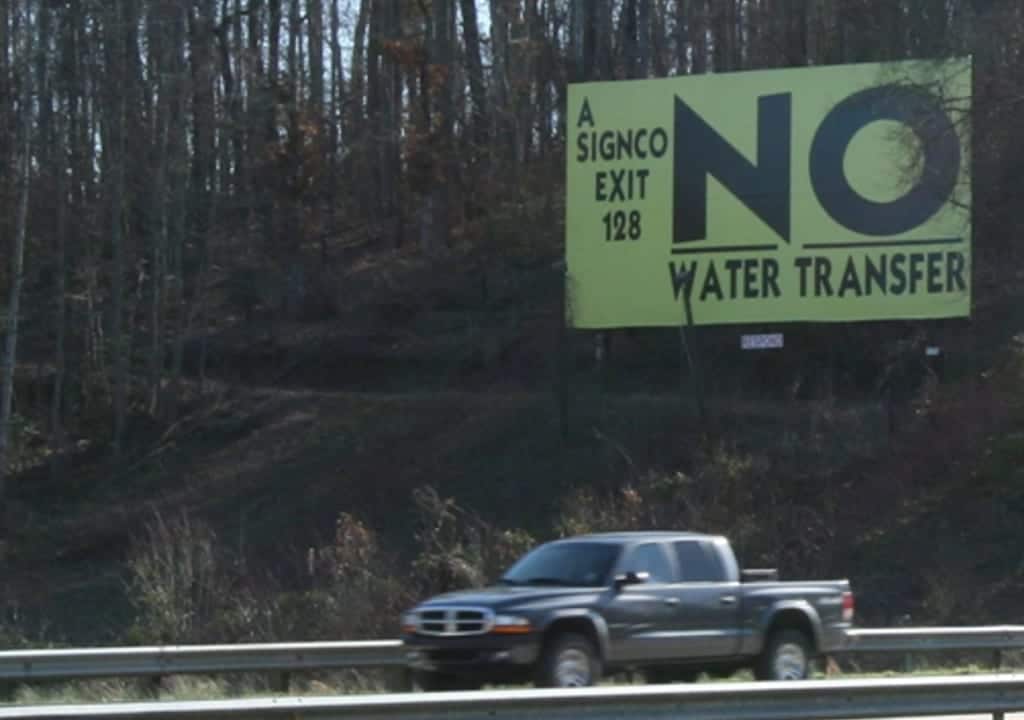

- Water transfers – do we have good ways of getting our water from an area with too much to an area with too little;

- Water infrastructure – is the way we get water to homes and businesses efficient, and what happens with water that has been used; and

- Water planning – do we have a system in place that assures we preserve this asset for future generations?

But these issues play out very differently across the world because within states or countries, water can be inconveniently distributed, and with water comes power.

Water is the all-important natural resource. Yesterday, a third grader reminded all of us, “Water is a world issue.” All of us depend on water resources for everything from drinking, growing food, washing, irrigation, and recreation to manufacturing, mining, navigation, and electricity generation.

All along our trip from the National Museum of Anthropology to the Teotihuacan UNESCO World Heritage Site, we have seen the image of Tlaloc. The roar or voice of the Earth, Tlaloc was a patron of water. With the Tlaloques, his assistants, Tlaloc was “responsible for extracting the water deposited on the mountains and letting it fall from the celestial plane from sacred pitchers that poured out their content,” according to an exhibit at the National Museum.

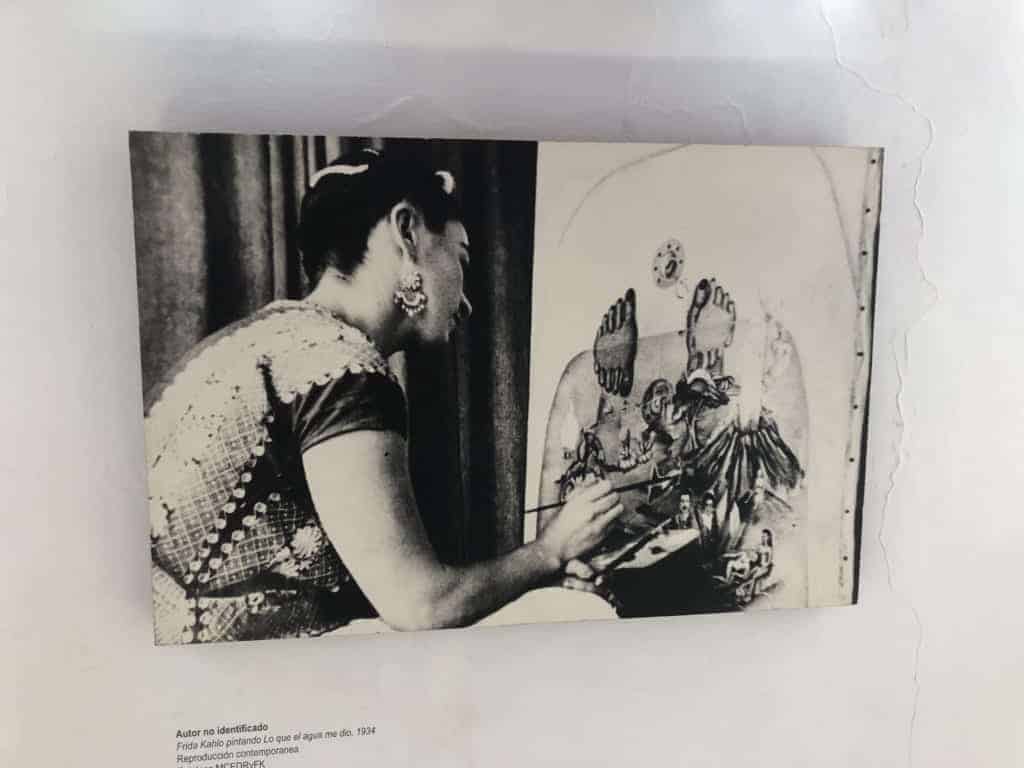

At Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo’s house in her bathroom, we saw her painting of the bathtub, “What the Water Gave Me.”

Our Earth is the water planet, but 97% of the planet’s water is seawater, which we cannot drink and is expensive to purify. From the Ancient Mariner, “Water, water everywhere, Nor any drop to drink.”

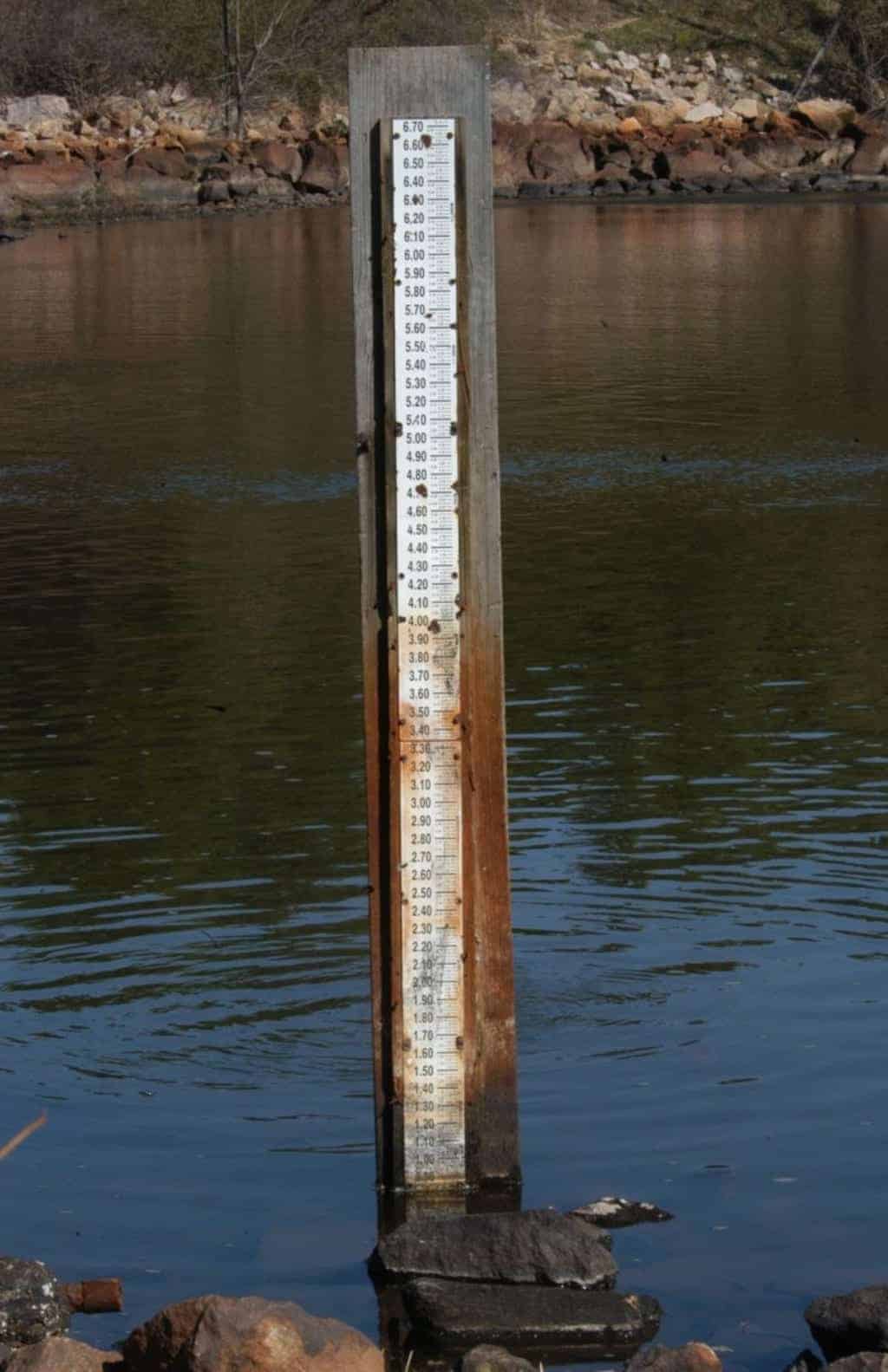

Think about the availability of water. North Carolina has 5,201 square miles of water, and the third highest number of private wells. Abundant rainfall recharges our aquifers, becomes groundwater, and runs off to the streams.

But North Carolina does not make good use of its “water budget.” Without ways to capture and store our rainfall, much of it evaporates. The precipitation is seasonal. Climate fluctuations lead to drought and flooding. Our population is concentrated in areas that have limited surface and groundwater. And agricultural, municipal, and utility use all peak at the same time.

From 1998 through 2002, North Carolina was in the midst of a four-year water drought. In October 2002, 246 water systems serving about four million people were under some degree of water use restrictions, and 15 water systems had fewer than 30 days of water supply left. The town of Cherryville actually ran out of water.

More recently, our problem has been too much water with hurricanes flooding our schools and communities.

According to the exhibit at the National Museum, “The Central plateau is one of the regions of Mesoamerica where life is marked by two clearly defined periods: the rains and the dry season. The former is a time of famine and suffering: to survive, food had to be stored that could go some way toward offsetting the ravages of hunger. The rainy season represented a revival: the heat of the sun and the humidity of the clouds — full of the precious liquid — made the land fertile and allowed plants, most importantly crops, to grow and flower.”

Historically, North Carolina’s water allocation policies have been driven by legal disputes. These policies have been premised on our ample water supply. Thus, the “reasonable” use of water has defined water policy in our state.

In 2007, South Carolina sued North Carolina about the equitable apportionment of the Catawba River’s water. That case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In some parts of our state, the issue has not been water quantity but water quality, as communities deal with contamination of their water supplies by bacteria, pesticides, or sewage.

Another dimension of the issue is the status of the state’s outdated water and sewer infrastructure.

The question remains how as a state do we move from crisis management to a more holistic, long-term water strategy?

In 2010, when I was studying water policy in North Carolina and around the world, I took my boys to Morocco — a leader in thinking about water policy. We learned that selling drinking water is a job. We saw state-of-the-art reservoirs. We saw several infrastructure projects, including an aqueduct system all over the country that was being put in as roads were built to provide water to rural areas. The aqueducts were covered to reduce evaporation. We saw innovative ways of getting water to tent communities in the Sahara, installing wells regionally and using what looked like industrial garden hose to move the water across significant distances. Solar energy was used to run the pumps. Morocco is tapping into underground aquifers — understanding that this source is unsustainable but nevertheless currently providing about one-third of the world’s water. And, we learned about cloud seeding — silver iodide crystals sprayed into clouds to generate rain.

Universally, people worry about water. Nine-year-old Sebastian Reyes worries about water. It is not a coincidence that the water system to harvest rainwater at his school is called a “Tlaloque 200.”

Water is the ultimate renewable resource, but most of it has to be provided locally, which can be challenging. Many think it will be the defining policy issue of the 21st century.