This is the third piece in a week-long series on schools, districts, and organizations across the state using data in innovative ways. Read the first piece on Shamrock Gardens Elementary School here, read the second piece on UNCC’s Institute for Social Capital here, and follow along with the rest of the series here.

Before Kelly Withers arrived at South Rowan High School five years ago, data was nonexistent. That’s according to Assistant Principal Amy Wise, who would know — she’s been at the school for 28 years.

“You would hear the term, and you would think that you were collecting and utilizing data, but pretty much it was not happening,” said Wise. “Teachers pretty much just went in and did what they’ve always done.”

The way things were always done wasn’t Withers’ style. Over the course of her first few years as principal, the school transformed from hardly acknowledging data to weaving it into every single thing it does. According to Wise, and a host of other teachers at the school, it took time, effort, patience, and a lot of strategy — but they can’t imagine where they’d be without that shift.

“Going from five years ago to today, it’s just like we’re a completely different school,” said Wise. “We have purpose now with what we’re doing.”

First step: A culture shift

When Withers arrived at South Rowan High, she shared information with the school’s faculty and staff on what key data points looked like and where they stood on a variety of metrics.

“Teachers looked at me like: What? It was apparent they had not really had that conversation previously, even at a really surface level,” said Withers. “We had to step back and talk about it differently.”

To begin shifting teacher’s mindsets around the role and purpose of data, Withers and her administrative team decided to hold data conferences with every teacher in the building. Teachers were given a presentation template and asked to fill it in with a range of data about themselves and their students — including their own attendance rate, their students’ attendance rate, discipline data, failure rate, and reflections on their strengths and areas for growth.

They were also asked to chart other factors, like how they spent their instructional time and what instructional strategies they used. For example, after tracking time spent on whole group versus small group versus individual work four or five times over the course of a few weeks, teachers assembled pie charts to visualize exactly how they spent their class time.

Then, over the course of three weeks, every teacher presented their findings to Withers and the full administrative team for 30 minutes — a process that was incredibly impactful for Amy Brooks, an English teacher at the school.

There’s great power in creating your own graphs and charts and having to come talk to administration,” said Brooks, recalling a pie chart she created to visualize how many times she wrote referrals and for what reason. “And you sit and you think. It really forces reflection. Where am I pouring my energy?”

South Rowan High School

– District: Rowan-Salisbury Schools

– Enrollment: 960 students

– Performance: Met growth in 2017 and 2018 after not meeting growth in the previous three years

– 49.5% of students are economically disadvantaged

– 83.1% four-year graduation rate

During their presentations, teachers discussed what they learned from the data and what they would do differently because of it. In turn, they became more comfortable with accessing data, tracking data, and setting goals based off of data.

“If I only ask you for your failure rate, I don’t get a holistic picture of what you’re doing in your classroom,” said Withers. “It took all these other data pieces to translate it — for some, it was instructional strategies, for others, they didn’t realize they missed eight days last semester. Obviously that has an impact on kids. And then, at the end, we asked them the same questions — now what are we going to do? What will be different going forward?”

Conferences were held twice: once in Withers’ first year, and once more the following year, when additional outcomes were added to the presentations. Now, those conversations are part of the culture of the school and happen more informally between teachers in the hallways, over lunch, and in their professional learning communities (PLCs). But this shift wasn’t without discomfort.

Brooks remembers when it was difficult for many teachers to do anything with their data because it felt like an indictment on their teaching.

“It was very personal. It was very hard to look at,” said Brooks. “We had to establish that this was not about looking at what you’ve done wrong, it was about looking at where your students were and not just doing summative assessments.”

Brooks recalled something Withers said that sticks with her today: “You can’t be afraid to look at the data.”

“It is very much a shift in culture,” said Brooks. “I have learned over these five years to take the personal part out of it. I no longer see it as my failure. I see it as an opportunity to help my students better and to become a better teacher.”

It all comes back to standards: PLCs and the data room

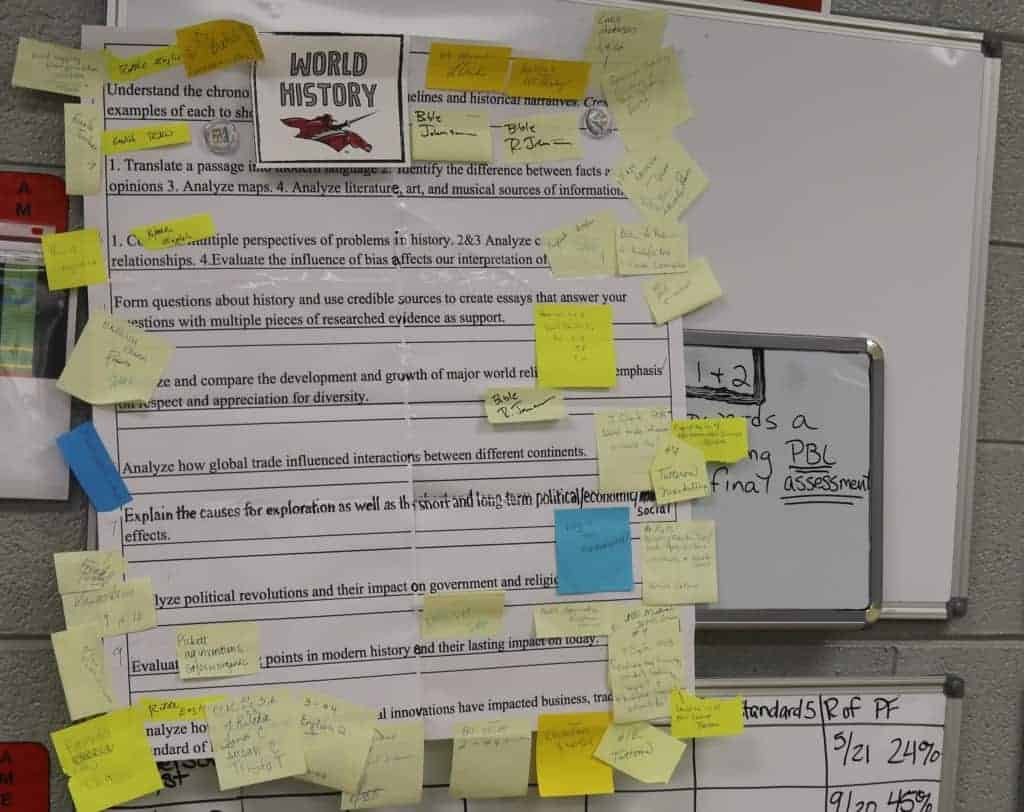

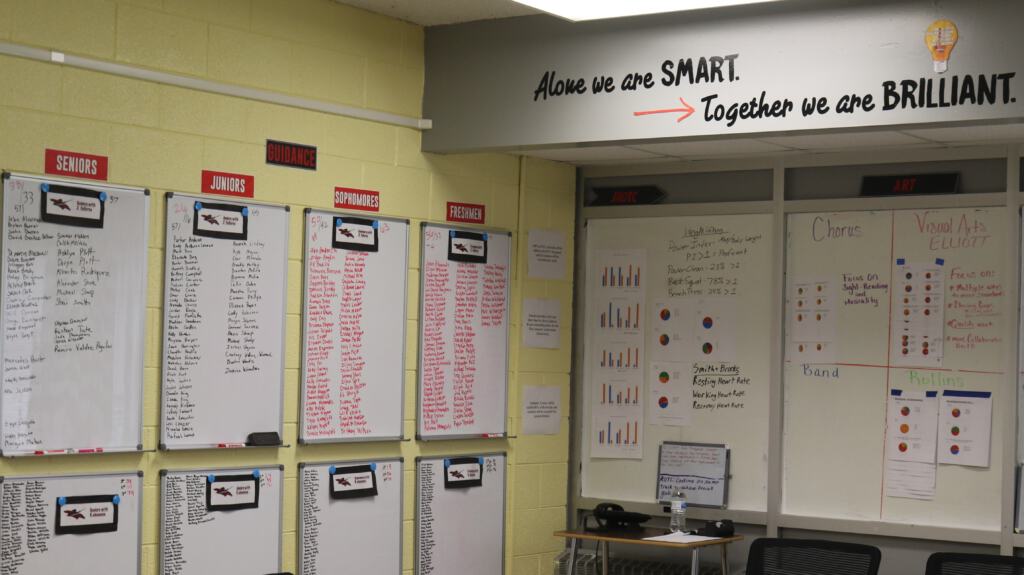

A few left turns past the main entrance of South Rowan High takes you to a large room with cork board, sticky notes, and posters covering every inch of the walls, each filled with data. What ultimately ends up on the walls is left for the teachers to decide, and the room may look completely different on any given day than the day before. Teachers continually update and refine their data as new information comes in and may even change what they’re measuring semester-to-semester depending on the students they’re serving.

But before teachers begin to track their students’ data in the room, they have to select what metrics they’ll include. And that all depends on what standards they are trying to assess.

Establishing fundamental standards

This year, Rowan-Salisbury Schools became the state’s first renewal district, which grants charter-like flexibility to every school in the district. For more on what renewal means, click here.

As part of renewal, teachers at South Rowan High have focused on establishing fundamental standards that boil down what they will guarantee every student knows when they exit each class. Through professional learning communities (PLCs), teachers have mapped out what those standards are, how to assess mastery in each of the standards, and how to ensure rubrics for assessing mastery are uniform across classrooms and content areas.

Inside the data room, where PLC meetings are held three times a month, there’s a poster titled “World History” that lists the department’s 10 fundamental standards — hardly visible behind a smattering of sticky notes from teachers in other departments.

“They could be clarifying questions: What does that mean? How will you know if a kid understands something? And the colored [sticky notes] are connections,” said Withers. “Not only is this student hearing it in world history, they may be hearing it somewhere else.”

This process allows every teacher in the building to visualize how much their own content crosses with other content areas — a first step towards the school’s plan to integrate different curricula together.

Tracking progress towards those standards in the data room

Once fundamental standards are refined and established, they are used to determine what data each subject area will track in the data room.

For Ashley Lanning, a math teacher and PLC coach at the school, determining what data to collect was one of the toughest parts of the process. A mindset shift was needed to go from assessing student behavior to assessing student knowledge as it relates to standards.

“I would assign homework, but I would just go around and spot check that they did it and the kids could put down just about anything — so really, what does that grade represent as a measurement?” said Lanning. “It’s a behavior. I never truly knew what they were doing. So that was a big shift for a lot of us to start collecting more data in the sense of accurate data, of what the kids actually know.”

Just as the standards vary from subject to subject, so do the metrics each subject area tracks in the data room. Withers and her administrative team push teachers to track data that’s not from standardized assessments. While some subjects still rely on them, others use commonly-created assessments that give students more choice when it comes to showing mastery.

According to Withers, this is another reason why clear fundamental standards are so important: Teachers have to recognize mastery regardless of form.

“Taking that away, the standardization of assessments, has been extremely uncomfortable for the teachers at times. It’s easier and certainly quicker to give standardized assessments, but they also recognize it’s not accurate,” said Withers.

Another issue with only tracking standardized assessments is timeliness. Before Withers arrived, teachers were accustomed to digesting one data point that wasn’t timely or actionable — the results of end-of-course exams for students they no longer had in their classrooms. The data room gives teachers a space to track other metrics on a more frequent basis, providing them with actionable insights.

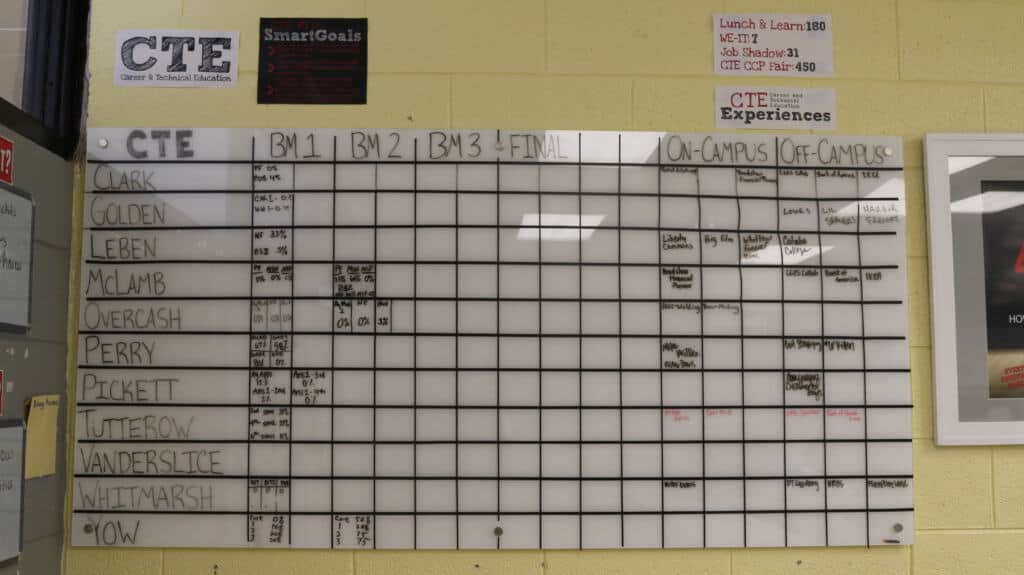

Every department takes part in the data room — including faculty who work with Exceptional Children (EC), English Language Learners (ELL), and Career and Technical Education (CTE). For example, the CTE department tracks both assessment data and the number of CTE experiences a student has. Those experiences happen both on-campus and off-campus and involve students seeing real-world applications of what they’re learning in the classroom.

Even the physical education department is involved. According to Jim Brooks, a health and PE teacher at the school, the department first started tracking data like the raw number of push ups or sit ups each student could do. But they quickly realized that type of data didn’t measure each student’s personalized growth over time, since students entered the class at different fitness levels.

That’s when the PE department wrote a grant for heart rate monitors. Now, at multiple times throughout the semester, students record their heart rate and how long it takes for their heart rate to recover.

Both figuratively and literally, the data room also serves as a graduation tracker for the school. By regularly monitoring assessment data, classroom teachers can get a sense of if each student is on track to pass their course, and the names of students with two or more course failures are written on whiteboards by the guidance department. In the final few weeks before graduation, a credit recovery board in the room tracks what students at risk of not gradating need to do to receive their diplomas. From that data, Withers and her team craft specific interventions for every student to get them across the finish line.

And while it was uncomfortable at first for some teachers to see data on their students visually mapped out in the room, Withers said that’s not the case anymore.

“We worked on transparency, we worked on the culture of our kids, we worked on the culture of owning where we are as educators and where we may need support,” said Withers. “We have to recognize where our strengths are and where we may be able to make an impact on kids, and where we may need a team to help do that.”

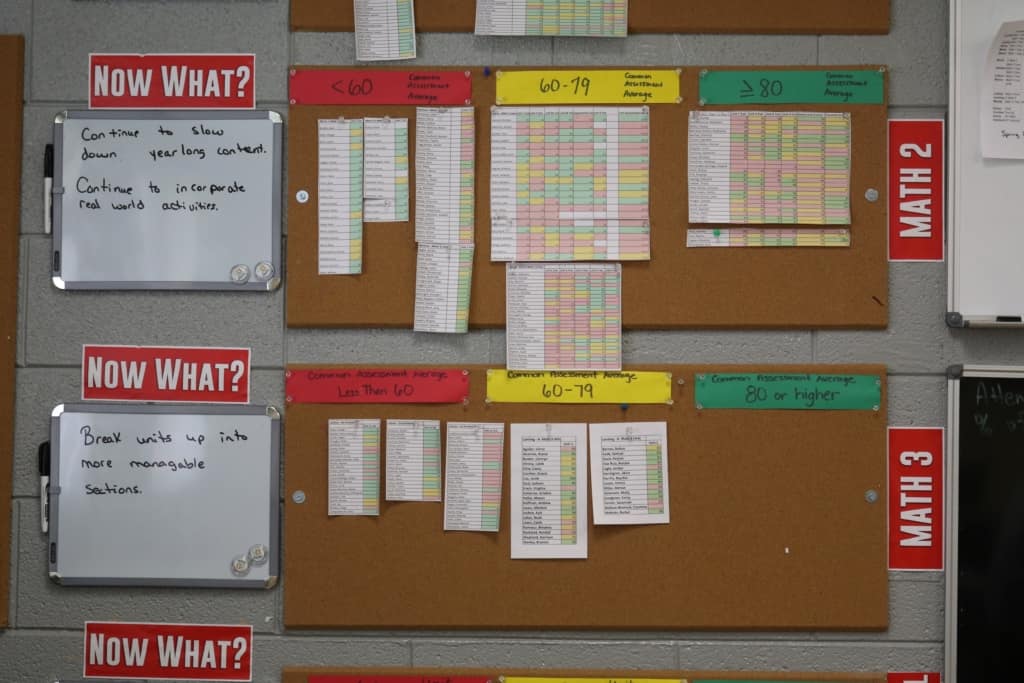

Now what?

In the data room, small whiteboards with the heading “Now what?” hang adjacent to every metric that’s displayed. That’s the question teachers at South Rowan High are constantly asking themselves and each other.

You tracked assessment data and see your students scored lower on this unit exam than any previous unit exam, now what? You tracked attendance data and saw a spike in students who have missed six or more days over the last two weeks, now what?

“We were finding that we’re gathering and collecting all this data, but we weren’t doing anything with it — that’s where the ‘now what?’ comes in. Now we know where our kids are, so where do we go from here to help them improve?” said Wise.

Sometimes, asking “Now what?” changes what a teacher or department decides to track entirely. Take the example of chronic absenteeism. When the data room first got off the ground, some teachers were tracking their attendance rates on the walls.

“And so we would ask the question, what are you doing about attendance? And they would say: ‘We aren’t doing anything about attendance.’ Then why are you measuring it?” said Withers. “That’s where the ‘now what’ boards came from. That’s the question we would ask them every single time — what is the data that you’re putting up there making you do? And if the answer is nothing, you don’t need to be measuring it.”

Now, the guidance department tracks any student with more than six absences, adding their names to whiteboards in the data room as the semester goes on. Unlike the case for classroom teachers, data on absences is actionable for the guidance department because they set goals around that metric and directly reach out to students and families who are missing school.

Tameka Brown, an intervention specialist at the school, said the visual display of both absences and failures in the data room is powerful.

“What I saw was a correlation between the absences and the failures and the grades from those benchmark tests. And all of us were able to see that, okay, this has a lot to do with why this student is here, because they’re not coming to school,” said Brown.

For Jackie Elliot, a fine arts teacher at the school, the “now what?” boards in the data room also serve as a tool to reconsider instructional practices.

“Does it need to be more spoken, more written, do we need to do individual projects, do we need to do collaborative projects — what way will best fit the student to learn the standard?” said Elliot. “Students have a lot of options for that in the visual arts. They can choose their subject matter, they can choose their medium in a lot of cases. … Is it a specific technique they need to learn? Where are their strengths? Where do they need to grow?”

Ultimately, data-informed practices have created a proactive culture of growth at South Rowan High. Leslie Sechler, an instructional literacy coach at the school, works to instill that culture in beginning teachers.

“Before we began this process, a lot of people looked at an assessment as an end. … But with growth mindset, there’s always an opportunity to learn and to grow and to get better,” said Sechler. “If you don’t see this as an opportunity for growth but you see it as an opportunity to label and to create an end game where you’re only as good as the number says, then we have to change the mindset.”

For Brooks, the shift from focusing on proficiency rates to focusing on growth has been an empowering one.

“I can get growth out of every student. That is within my control. I can’t help what the elementary or middle school could’ve done. I can’t control their home environment. I can’t control their poverty — but I can get growth out of every student,” said Brooks. “I can do that.”