As part of the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research’s statewide study of equity, I met with the Office of Equity Affairs for the Wake County Public School System toward the end of the 2017-18 school year. This article represents a case study in a new series called Promising Practice — the culmination of interviews, observations, and interactions over a six-month period.

It’s a muggy late May afternoon in Wake County. The mixture of heat and humidity is made worse by off-and-on showers that leave a thick blanket of moisture in the air. However, my mood is instantly made better upon entering the building at Rolesville Middle School. The principal, Tad Sherman, greets and escorts me into a room filled with around 15 energetic yet studious eighth graders. They are a well-balanced mix of different hues, cultures, and genders. Their desks are arranged in a semicircle, ideal for facilitated dialogue.

These are the members of the school’s student equity team, an extension of the broad efforts initiated by the Office of Equity Affairs for the Wake County Public School System, and they’re already engaged in discussion when I arrive. This is their first time meeting since the Student Equity Summit, a convening of other students from equity teams throughout the district. They’re debriefing about how the event met their expectations and the changes they’d like to see at the school.

“Racism never really left,” one student says. Another adds, “If adults could help out a little bit more with the environment, and teaching people to be more diverse, it would help out a lot.” The conversation spans a multitude of different directions and is facilitated by an adult on staff who is part of the school’s equity leadership team. She speaks just enough keep the conversation flowing, but make no mistake, this is a conversation led by students.

They discuss a curriculum more reflective of all humanity and not just Europeans, increasing role models of color at the school and leaving seventh graders in a better position to lead the equity work. One white female student reflects, “Before this group I didn’t really pay much attention to [racism].” She says coming to the group has helped her talk about it and increased awareness.

They embody a wisdom that stretches beyond their age. They feel their generation is better at handling “these sort of things.” But more than that, there’s a clarity on the socializing function of education.

A young mixed-race girl states, “School is like a train station. All sorts of people go in and out of it.”

“It’s important not just to talk about how race affects us at school, but everywhere else.”

She ends by saying, “What you bring with you, is what you take out.”

***

Under the leadership of Dr. Rodney Trice, assistant superintendent for equity affairs, they’ve assembled an all-star cast of five additional team members to fulfill the mission of equalizing educational opportunity in Wake County. While the office supports all student subgroups (LGBTQ+, low income, students with disabilities, gender, etc.) race is central to its function. For years, Trice was on a bit of an island, pushing hard to cure inequities for historically marginalized student populations solo. Now, by surrounding himself with colleagues skilled in a variety of capacities, he and his team are perhaps better positioned than any other district to bring the work of equity to scale.

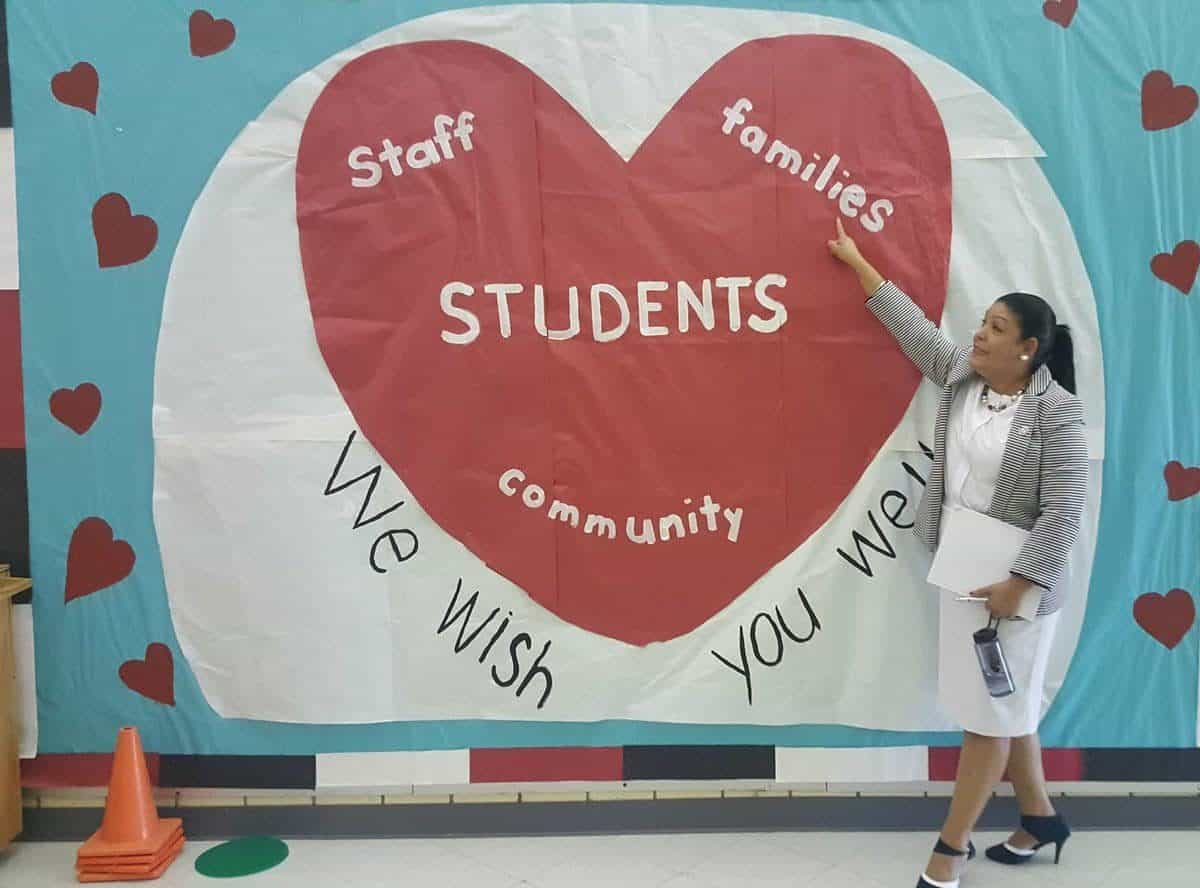

While a handful of districts in North Carolina have dedicated equity officers, Wake County stands out by staffing an entire office. The team members are Lauryn Mascareñaz, director of equity for coaching and leadership; Christina Spears, special assistant/coordinating teacher in equity affairs; Dr. Maria Rosa Rangel, director of equity for family and community engagement; Teresa Bunner, director of equity for student engagement; and Pamela Gales, historically underutilized business program manager. They each serve a particular function grounded in a strategic approach to ensuring equity throughout the district. Trice says that although the pursuit of equity means striving to decrease the gaps between the highest and lowest performing students, it’s really about raising achievement for all — the two aren’t mutually exclusive. So long as there are inequities, all students suffer, even if they don’t know it.

Wake County Public School System (WCPSS) created the Office of Equity of Affairs in 2013, but it remained unstaffed for a year before Trice was hired. “The impetus for the Office of Equity Affairs grew from work that the school board was doing around equity during the years of probably 2009-2011,” Trice says. His arrival was precipitated by the Wake County School Board decision to create a position to ensure the system was being equitable to historically marginalized students. The move was championed by board members like Keith Sutton and community organizations such as the Education Justice Alliance, the Raleigh Chapter of the NAACP, and the Coalition of Concerned Citizens for African American Children. Dr. Trice came to WCPSS in July 2014, after having worked in Chapel Hill-Carrboro School System. He admits that the first years were tough; he was basically a team of one.

“We needed to attack many of the issues and hurdles that students and families face in a more systemic nature,” he says. He served as an appendage of the district that engaged with the community and stakeholder groups who demanded better education for underserved student populations. “Equity work is, I believe, inherently resistance work,” he says. “If we’re not careful to continue to get that push from community it can become […] a checkmark.” Trice’s ability to commune with parents and activists earned him the respect of the community, but not the positional power to enact change on the scale needed. For him, having a team helps ensure the voices of students and families, as well as teachers and leaders, continue to be a part of what drives the activity.

***

Wake County Public Schools System is the largest school system in the state, with an enrollment of 164,663 students across 187 schools. It is consistently high performing and nationally regarded as one of the few systems with a high degree of racial and socioeconomic diversity. But in recent years, WCPSS has also endured some negative attention with race playing a central role. When video of an African-American girl at Rolesville High School being slammed to the ground by a School Resource Officer went viral in 2017, it stirred outrage on social media. Months later, news reports revealed that Black students in WCPSS are disproportionately referred to law enforcement. Later in the year, a white student at Apex High School tore down an art installation, which read, “My Blackness is Not a Weapon.” These incidences dominated headlines, but do not render an accurate picture of the work being done to deal with issues of race.

What has not been as well-publicized is the activity of the Office of Equity Affairs. The team’s locus is wide-ranging, but generally fits into three buckets: 1) community engagement, 2) coaching and consultation at the school level, and 3) coaching and consultation at the district level. The strategy involves being visible and present in the community in a meaningful way, but also working with parts of the district to build relationships that lead to improved outcomes. From attendance at churches, to discussions about building construction, to anti-racist professional development, to convenings for students and staff, to responding to racially-charged incidents, it all falls within the scope of Equity Affairs.

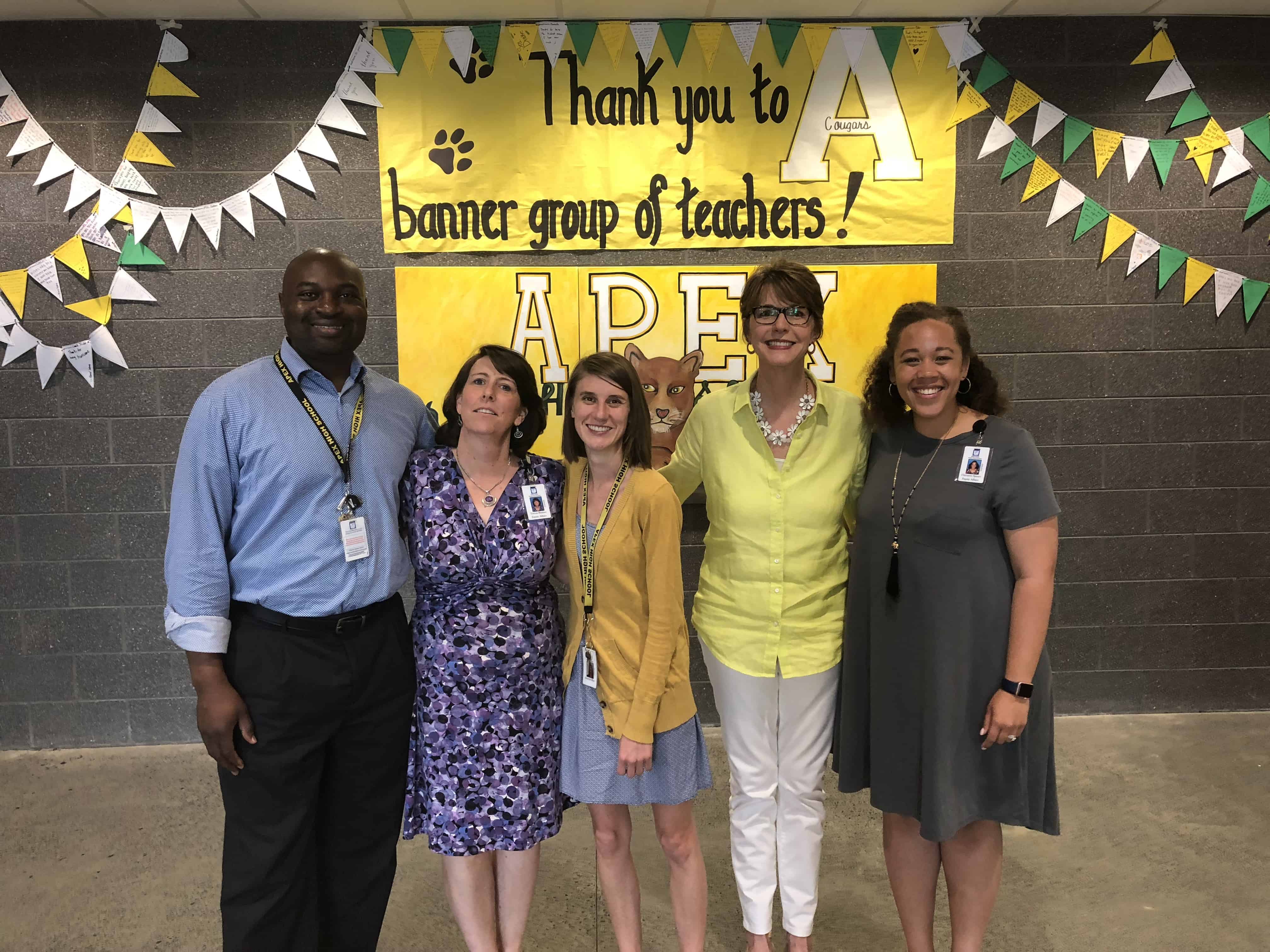

Take the case of the Apex incident in Spring 2018. For context, nearly 80 percent of students at the school are white and only 13 percent are free-reduced lunch, according to Principal Dr. Diann Kearney. However, after an art teacher taught a unit on activism, students created the “My Blackness is Not a Weapon” installation to protest police shooting of black people. They displayed it in a high-traffic hallway. It didn’t take long for the artwork to generate discussion among staff and students. Immediately after a white student took it upon himself to tear down the display, the Apex school leadership reached out to Equity Affairs to assist in their response.

“I’ll be honest, it was a really challenging time,” Kearney said.

Black students were particularly troubled by what the act meant about their place in the school and society. Equity Affairs was dispatched to help create safe spaces for the school to dig beneath the surface of the incident and for students to engage in honest dialogue about their feelings.

“The equity team was there really every step of the way to facilitate that,” career and technical education teacher Rodney Obaigbena says. “It just really makes me feel good to know that we have that team and the partnership.” This led to the eventual creation of the student equity team to help continue the conversation. “It’s an issue affecting all of our students … and should be addressed by all of our teachers,” said behavioral support teacher Anna-Lee Rose. The staff senses that students are encouraged by adults starting to take their concerns to heart.

***

What’s remarkable about the Equity Affairs team model is that it undergirds every aspect of the district. The team’s work follows wherever inequity exists, which by nature makes it multi-pronged. In a given week, the team may conduct Twitter chats and provide popular education, then facilitate parent workshops with multilingual stakeholders, while also hosting professional learning on culturally-responsive teaching with WCPSS staff and leadership. In December, WCPSS brought in renowned journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones to talk with district personnel about school resegregation. Three days later, after closing schools due to snow, the district’s official Twitter account posted a thread, defending the countywide public school system as away of preserving integration. While the work of equity is hard to quantify, if these anecdotes are any indication, the message seems to be sticking.

Long thread about our countywide school system and inclement weather. Grab a mug of hot chocolate and listen in. https://t.co/l5LKWo2vYh

— Wake County Public School System (@WCPSS) December 9, 2018

But they have not lost the grassroots approach that characterized their earliest work. They note WCPSS Superintendent Cathy Moore and the Board of Education as some of their most ardent supporters.

Still, this work has not been without detractors. Lauryn Mascarañez caused outrage during Thanksgiving for a tweet encouraging teachers not to appropriate Native culture by having children dress up as “Indians.” While her commentary captures the heart of the culturally-responsive pedagogy teachers ought to embody, a few community members were put-off by the suggestion, causing some public outcry. The district ultimately stood behind Mascarañez and her comments, but the incident revealed the challenges associated with equity work — it’s often messy and can be sensitive.

The Equity Affairs team created a culturally-responsive framework that includes several dimensions, one aspect of which is developing equity leadership at every level of organization and deputizing people to act. In addition to forming community and district equity leadership teams (CELT & DELT), schools are also encouraged to create student equity leadership teams like the one I witnessed at Rolesville. Perhaps the most noteworthy example in the county is Enloe High School’s “Enloe 5” model. Under the leadership of WCPSS Principal of the Year Dr. Will Chavis, the Enloe staff assembled a cadre of students who meet to discuss issues of race with the administration. The students also lead teachers in how to incorporate strategies that best reach the various student populations. Enloe is a magnet, with a diverse population that houses several academies. Given this context, Dr. Chavis says their approach to equity has to be tailored to fit their needs.

The “Enloe 5” teacher strategies are 1) proximity (e.g., closeness, relationship-building, etc.), 2) addressing race, 3) checking for understanding, 4) connection to student lives/future selves, and 5) visibility (e.g., seeing students, visual representation). One key point: the strategies weren’t selected by teachers. The students selected them after reviewing a list of research-based strategies. The students credit the equity work at Enloe for allowing them to have a stake in how their education is delivered. In addition to support from the Equity Affairs office, Enloe has also been receiving consulting from the Equity Collaborative to help guide implementation.

Equity Affairs doesn’t want to control the approaches of individual schools. Instead it wants the students and staff at each school to determine what works best for them. There are an assortment of activities taking place throughout the district, all philosophically connected to the mission and vision of equity: school book clubs, field trips to the Race: Are We So Different? exhibit, film screenings, community forums with parents, and weekly equity-focused PLC meetings.

There is much to be proud of in the short time the office has been in operation. But how will Equity Affairs gauge success? In addition to seeing improved outcomes, if the team can focus on the cultural responsiveness framework and affirm students’ selfhood while pushing them to perform academically, Trice and his staff believe their work will matter. They’ve begun surveying students and parents about their experiences and hope to get robust feedback. When parents know how to advocate, teachers feel supported in their development around equity, and students are given authentic voice, good things are bound to happen. This is the theory of change. Though still learning, Equity Affairs is raising consciousness in the district. It’s a new day and freely discussing issues of race are no longer considered taboo. Good work is being done all over the state, but WCPSS is making equity part of its identity and providing a useful template for other districts to emulate.

While the term “woke” is overused, it does denote a sense of socio-political awareness. It doesn’t just mean knowing better, but doing better. So, here’s to making Wake County a more “woke” county.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Diann Kearney is no longer the principal at Apex. She now serves at Green Hope High School in Cary.