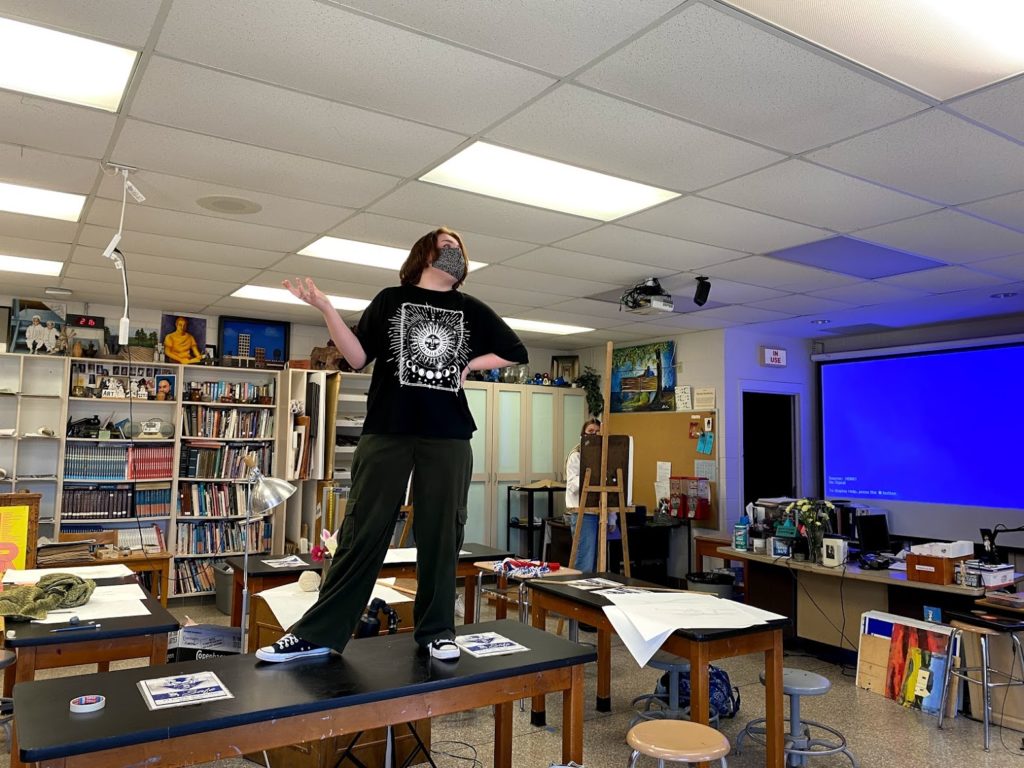

In Sean Parrish’s Art II class, a student climbs on top of a desk, strikes a pose, and then Parrish alerts his artists that the timer is starting. Today, the class is diving into gesture drawings — live drawings on the human form — and the models in this class period are coming from the audience.

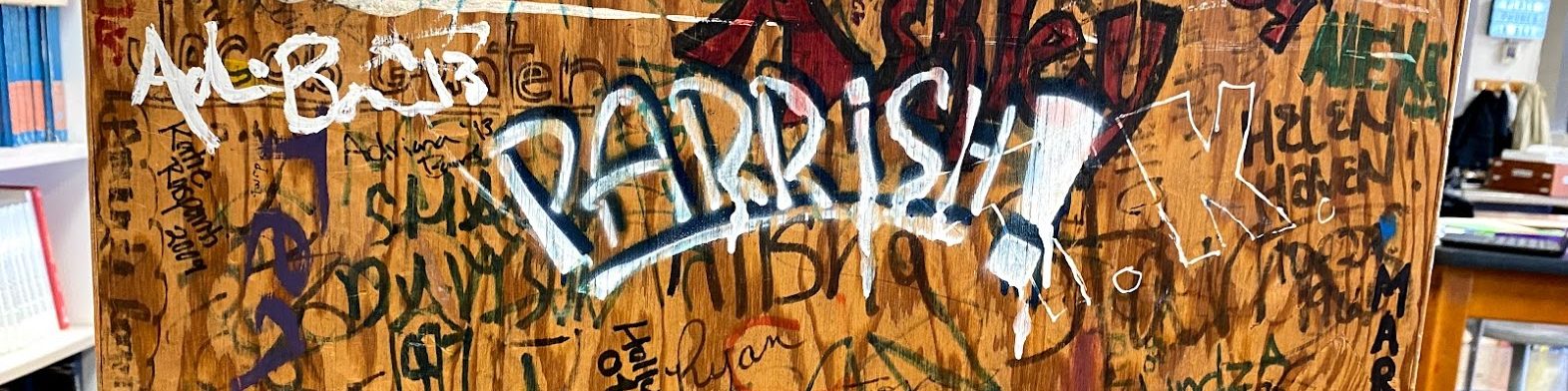

The model stands in the middle of Brevard High School’s art studio and is surrounded by almost three decades of student masterpieces. Parrish has taught in this room for 28 years, but his students’ art can’t be contained by these four walls.

The hallway leading to his classroom is lined with a permanent art collection, a legacy gift by members of the school’s National Art Honor Society. Looking through the windows of that hallway, there are art installations outside in the spaces between buildings. When you enter the school and go to the main office for a visitor’s pass, there is an official student-run art gallery.

How did this Transylvania County school become a walking art exhibit? The most obvious answer is due to the humble and unwavering leadership of the school’s visual arts educator, Sean Parrish.

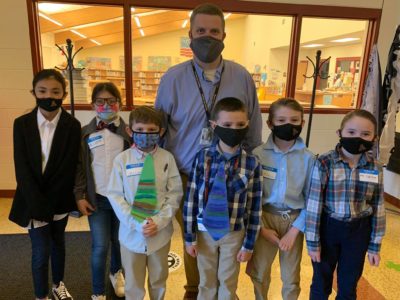

Visual arts educator Sean Parrish

Parrish arrived in Brevard with a degree from Elizabeth City State University, and his personal goal was to grow the visual arts program. When he started teaching, the farthest a student could go in visual arts was Art III, and it was treated like an independent study class. He wanted to give students more options and make those advanced classes more intentional. Parrish changed what was happening in Art III and created an Art IV course, which is a pre-requisite for the now available Advanced Placement art course.

The AP Art students are in charge of the official art gallery, which sits near the entrance of the school. Putting on an art show is part of their curriculum and one of their exit requirements for class. The students learn how to set things up and work together deciding what to display. They do the framing, hanging, and naming of the show. They create invitations, and in years prior to COVID-19, families of the students attended opening night.

“It’s just now an official gallery with the proper ambience and proper reverence to the students’ work. The pride that I see kids have when they see their work hanging in the gallery, or the excitement when they say they’re going to have something in this art space, [is rewarding].”

Sean Parrish, visual arts teacher at Brevard High School

Parrish has had a couple of students who have gone off to study art in college, and they tell him they were thankful for the gallery experience because they felt ahead of their peers. The gallery not only serves as a learning tool for art students, but it also provides a place to cultivate art appreciation for the entire student body.

Parrish has also created opportunities for students outside of the typical school day. In his second year, he established the Art Guild, a club for anyone who is interested in art and wants a space to be with others who feel the same. And then, about 10 years ago, he added the National Art Honor Society, a club that requires a specific GPA to join as well as volunteering for community service projects.

Lauryl Meile, who is a senior and president of Brevard High School’s National Art Honor Society this year, served as a model during one of Parrish’s Art II classes when we visited. She has taken four classes with Parrish and intends on pursuing a degree in studio art, focusing on ceramics, photograph, and graphic design at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

“I’ve gotten a lot of great experience through this class, and I think it’ll put me ahead of the game when I go into an art degree. So I am excited to use the knowledge I’ve learned here.”

Lauryl Meile, senior at Brevard High School

At Brevard High School, Parrish’s visual arts classes continues to thrive, even in a year of hybrid schedules and virtual learning. What has this year looked like and felt like for him and his students?

Visual arts in the time of COVID-19

This year, like so many other places and spaces, looked different at Brevard High School. The school was one of the first high schools to move to a plan B hybrid schedule, a mixture of in-person and virtual instruction, in North Carolina. And this hybrid schedule brought both challenges and opportunities.

One positive Parrish noted was the smaller class sizes. It allows for personalized attention to the students and their work. The hybrid schedule also lends itself to slowing down the pace of study, and Parrish says it’s hard to get through more than 50% of the curriculum. Students and teachers alike have trouble with virtual learning, whether it is getting assignments turned in on time or identifying where the disconnect may lie in understanding of a concept.

In the fall semester, Parrish had students make sketchbooks in class, and that’s how they accomplished work when they were at home. When the class was virtual, they would sketch at home and either bring their sketchbooks in to show Parrish when they were in-person, or take pictures and submit their work virtually.

Next school year, when school may return to a more normal format, Parrish is concerned about the number of students who will be able to sign up for the arts. Since the arts are considered elective courses, students who have fallen behind in regular courses will have to retake classes in order to stay on track for graduation. They won’t be able to take electives until they are caught up, and with smaller beginner courses, it’s harder to grow advance courses.

“It’s been weird,” says Isabelle Lefler, a sophomore student in Art II, of the 2020-2021 school year. “But I’ve been thankful that we can come in a little bit.” She feels her skills have improved because of Parrish and likes the way he instructs class.

What would Parrish like to see more of for the arts in North Carolina? An understanding that his discipline, and all the other arts — dance, theatre, and music — aren’t just hobbies. That the arts stimulate higher learning, and are just as important as other subjects. I believe decades of his students would agree.