You have probably seen the commercial on TV or online. Advertising a travel website, the commercial depicts a frazzled teacher who has lost control of her classroom, yearning for a vacation while her kindergarten students create bedlam behind her. All in all, it is an insulting farce.

And yet, the commercial draws on one of the two competing narratives that regularly drive public perception of public schools and teachers. Schools would improve, this narrative suggests, if they could get rid of teachers who know too little of the subject matter or do not know how to engage students in learning. In their concern over middling test scores and ill-prepared graduates, policymakers and corporate leaders have pushed educators to identify and dismiss the most ineffective teachers.

The alternative narrative holds up the especially creative, challenging, and emphatic teachers. We fondly remember the favorite teachers who helped shape our lives. On a regular cycle, we celebrate the “teachers of the year’’ in our state and school districts. Savvy parents come to know to which teachers’ classes they want and hope their children get assigned.

There is, in fact, a third story that deserves attention as North Carolina confronts the multiple, intricate issues involved in addressing the shortage of teachers and in filling the teacher pipeline with a steady stream of high-quality teachers. The story emerges from data and research over several decades, synthesized in a 2013 study commissioned by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The study looked at more than 3,000 teachers in seven major metropolitan areas, including Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

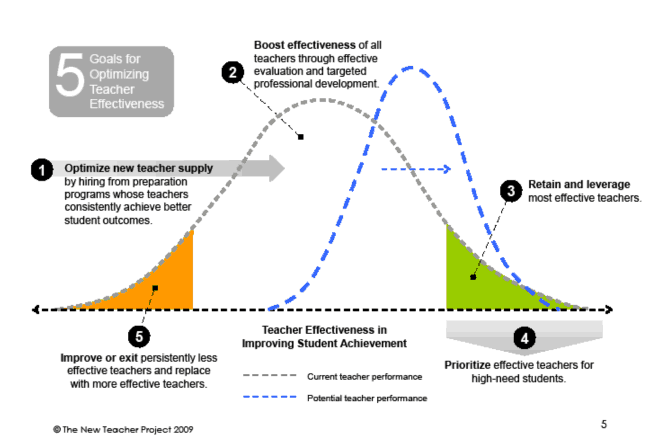

See the bell curve below. There are a few teachers on each end, with most in the large bubble in the middle. About four percent of the teachers scored into the highest-performing category, and 7.5 percent scored on the low-effectiveness end. In the middle, the study found little difference among the teachers, concluding that “this would suggest a large middle category of effectiveness with two smaller ones at each end. Rather than trying to make fine distinctions among teachers in this vast middle, efforts would be better spent working to improve their practice.”

In reflecting on this study as well as EdNC’s insightful, weeklong exploration of the North Carolina teacher pipeline, let me offer a few observations and points of emphasis. I also draw on my eight years on the board of trustees of the N.C. Center for the Advancement of Teaching.

- The recent teacher pay raises, enacted by the General Assembly and supplemented in some counties, are welcomed, but not sufficient to make up for the erosion during the cycle of recession and state budget austerity. The political squabbling over North Carolina’s ranking among the states is based on an inadequate yardstick. As a sustained effort to attract talent into classrooms, the state should align teacher pay along standards of compensation for middle-class professionals.

- The state needs to restore cutbacks in professional development — and indeed do what major corporations do in enriching the skills of their professionals. As the Gates study suggests, efforts to improve the effectiveness of the teachers in the bell-curve middle would pay off in elevating student performance. What’s more, the state can reduce its “shortage’’ not only with increased enrollment in teacher-training institutions, but also by giving encouragement to competent teachers to stay one, two or three more years in the classroom.

- North Carolina has implemented programs, based both on student-achievement data and on in-class observations, to rate teachers. Still, it remains difficult — and controversial — to assess teachers. In some rural counties, school administrators may have no choice but to hire the few available teachers, whatever their effectiveness. However difficult, dealing with ineffective teachers is crucial to sustaining confidence in public education — parents will send their children elsewhere rather than see them “lose’’ a year or two of education progress.

- As daunting as it may be to address, North Carolina and its school districts face a persistent equity issue in the distribution of teaching talent. In both rural and urban counties, schools with high enrollment of students from low-income, Spanish-speaking and black families tend to have faculties consisting of more inexperienced and near-retirement teachers, and fewer high-flying teachers. A major need is more men, especially black men, in classrooms.

As someone born and reared along the mighty Mississippi, I have been thinking of a substitute metaphor for the teacher pipeline. To me, it is also akin to a river system, with not only a main flowing channel but also creeks and tributaries, dams and diversions, outlets and islands. North Carolina should want to meet the challenges in marshaling its educators and its aspiring teachers into a mighty flowing force. And, turn off that darn TV commercial.