This is an article about phonemic proficiency.

Don’t click away to that post on Three Ways to Fix Reading Scores Instantly just yet. Phonemic proficiency might not sound exciting, but it might be the one skill that sets up beginning readers for success in every other aspect of reading.

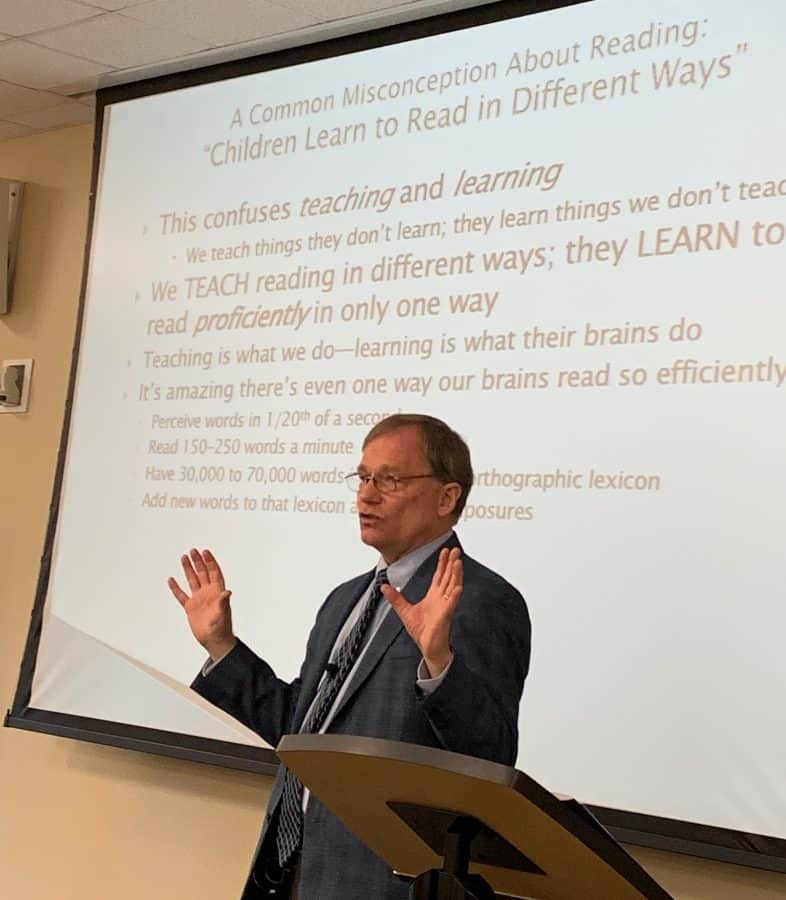

That’s what author and researcher David Kilpatrick told a gathering at the Hill Center in Durham last week. At a time when reading experts caution that there’s no silver bullet that will teach kids to read, Kilpatrick is careful not to claim that phonemic proficiency is a cure-all. But he does say proficiency with phonemes (units of sounds) is vital to unlocking the door to skilled reading.

In fact, he goes a bit further — saying that a person’s future prospects may depend on learning phonemic proficiency.

“I remember some of the reading teachers that I worked with, they said, ‘You’re like a one-trick pony with all this phonemic stuff,'” Kilpatrick said. “And I said, well yeah, because this is the missing piece. This is the part that’s not allowing us to move kids forward.”

So what is it?

Let’s start with orthographic mapping

Stick a pin in the idea of phonemic proficiency for the moment. Start with this question: How does a word jump out at you and you can’t help but know it?

That’s the product of something called orthographic mapping — through which readers automatically build a bank of tens of thousands of words. Kilpatrick says that bank is the key to reading fluency and, ultimately, comprehension.

He laments edicts like: By the end of kindergarten, students should know 50 or 100 words. Why teach them 50 words to memorize when you can teach them how to map any word they come across?

“How many of the words that you know were you taught?” Kilpatrick asks.

Researchers have written about orthographic mapping for almost 50 years. Kilpatrick, like most researchers of reading, came across it through Linnea Ehri’s work dating back to the 1970s, which says it is the mental process we use to store words for “immediate, effortless retrieval.” David Share, chair of the department of learning disabilities at the University of Haifa, followed up with his self-teaching hypothesis. This says we teach ourselves most of the words we know if we are able to make connections between the graphemes (letters) and phonemes (sounds). One word at a time.

Kilpatrick says that as we learn to manipulate phonemes and understand the rules for how letters and sounds work together in written English, we sound new words out correctly, and that through repetition – Kilpatrick says it’s as quick as one to four exposures – we remember the new word. At that point, we aren’t sounding it out. It jumps off the page as a known word; a remembered word. A sight word.

The term “sight word” is used in many contexts. Some use it to describe the relatively few words in the English lexicon that disobey phonemic code. Kilpatrick uses it to describe any word that we know just by looking at it – because we’ve decoded it and internalized it after a few repetitions.

“In other words,” Kilpatrick said, “orthographic mapping is what we do to make an unfamiliar written word into an automatic ‘sight word.’”

If a learning reader understands the phonemic rules of English, he or she can decode and map any word — even a nonsense, made-up word. And with the ability to independently decode and map, a new reader is off to the races building fluency and vocabulary.

“Orthographic mapping proposes that we use the pronunciations of words that are already stored in long-term memory as the anchoring points for the orthographic sequences, the letters, used to represent those pronunciations,” he said.

To do that, though, a student needs advanced phonemic awareness, letter-sound knowledge, and phonological long-term memory – which all work together to help us produce a long-term memory of the words we learn. This is phonemic proficiency.

How orthographic mapping starts with phonemic proficiency

It breaks down simply to awareness of different sounds in words (phonemes) and word-letter recognition.

So when a new reader comes to the word “red,” teachers should break it down into its three phonemes: /r/, /e/ and /d/. The new reader may sound the word out a couple more times, but then it’s mapped.

The teaching process looks like this, he says:

- Introduce the word orally first.

- Segment into phonemes verbally.

- Emphasize each phoneme.

- Ask for letters associated with the phonemes.

- Display the word and work through the sounds together.

Kilpatrick says this is the entry point for learning sight words, not through visual memory.

“A growing amount of research suggests that for typically developing readers, phonic decoding may be the gateway to sight-word learning,” he said. “By itself, phonic decoding is not capable of producing sight-word memory, yet it appears to provide the opportunity for such learning.”

The process works for so-called irregular words, too. For instance, if a new reader has learned that the /e/ in “red” makes a certain sound, he or she may believe that the word “said” should be spelled s-e-d. Kilpatrick goes through the example.

“What’s the first sound in the word ‘said’? he asks.

“Sss” hisses the crowd.

“What’s the next sound?”

“/e/” comes the response.

“And the last?”

“D.”

Simple enough. But then he models the next part of the teaching lesson. He goes to a whiteboard and asks, “How are we going to make the ‘Sss” sound”? And he writes an “S” on the board. “How are we going to make the ‘D’ sound? And he writes a “D” on the board. “What about the /e/?” And the audience, fully aware of the correct response, gives one instead that a non-reader would. “E”?

Kilpatrick writes “AI” on the board and explains that in this word, the /e/ sound is written like this. He then sounds out S-AI-D.

Now, he says, breaking character from the teacher, those kids are going to see the word “said” a lot in their reading. And they’re not going to have to sound it out anymore.

“That’s what we want to train,” he said. “That’s what kindergarten should be all about. Kindergarten shouldn’t be about teaching kids to read [books].”

The link between phonemic proficiency and future outcome

What does it mean? It means, Kilpatrick says, that phonemic proficiency is the foundation for unlocking orthographic mapping. And orthographic mapping, the skill needed for remembering words, is the key to fluently reading and building vocabulary. And all of it is necessary for skilled comprehension.

Kilpatrick goes further, though. He says skilled reading comprehension is necessary for doing well in math, science, social studies – every subject, really. And doing well in other subjects is needed for college success and/or prosperous career opportunities.

He connects a person’s outcomes in life to the pivotal skills in phonemic proficiency. And it’s not a stretch, he says.

“It is a reality that this is a factor that has huge reverberations all the way up the line,” he said.

In part, it’s the gravity of impact that learning to read has on an individual that drives Beth Anderson in her work at Hill Center. Anderson became the executive director of the center six years ago — about the time Kilpatrick’s book, “Essentials of Understanding and Assessing Reading Difficulties,” was published.

She knew instantly that it was a text her instructors needed. Six years later, his insights are what teachers in North Carolina should hear, she said.

“It’s a really exciting and critical time in North Carolina with mounting efforts to advance the science of reading and support educators in really having access to the knowledge, the tools and the training they need to deliver research-based instruction,” she said.

“There’s lots of debate. I’m sure a lot of you are following it. Some dissension, some disagreement even over language and what’s proven and what’s not. But we can say with absolute certainty that phonemic awareness and proficiency are essential skills for learning to read, and that all students benefit from systematic, explicit, direct instruction.”