Leaders of Edenton-Chowan elementary schools were prepared to recommend that their district’s school board move them to full in-person instruction when Gov. Roy Cooper announced the possibility this month.

“We were like, oh yeah, plan A, let’s do it. Because we can fit, and we can do it,” said Sheila Evans, principal of White Oak Elementary, a pre-K-2 school connected to D. F. Walker Elementary, its 3-5 grade counterpart.

Superintendent Michael Sasscer said they knew they could fit all of the students in their two elementary schools when they started the year in plan B. Plus, in-person instruction is best for early learning and development, he said.

“What’s developmentally appropriate for teaching a child how to read is face to face instruction, as well as all the other factors: socialization, teaching communication skills, collaboration. That works best in that personalized, small-group setting,” Sasscer said.

On a personal note, he had seen the difference returning to school made in his son, a second-grader who struggled through social isolation in the spring and summer. After five days of school, he said, his son had “completely leveled off.”

“I personally have seen, and certainly through observation, walking the halls, being in classrooms, it’s a wonderful, positive moment in our school system to have kids back in the building.”

But a week later, Sasscer, Evans, and D.F. Walker Principal Linda White had changed their minds. Sasscer recommended to the board staying in plan B, and the board voted to do so for the rest of 2020.

When I visited the day after that vote, Sasscer told me:

“It’s really about that balance of what you can do versus what you should do,” he said. “When you have a shared perspective, and you really champion collective voice, then I think you come to a more balanced approach as to what’s best for the health of our students, our staff, and our educational program, and we feel this is really going to allow us to sustain and continue momentum forward.”

“We needed to slow down.”

Evans had spent recent days overseeing the isolation of about 10 children who had been exposed to a COVID-19 case on the bus, where students, who were sitting one to a seat, still weren’t six feet apart. Evans took it as a moment to pause. “We needed to slow down,” she said.

Evans also had spoken to several teachers, including Lisa Chappell, a kindergarten teacher in her 25th year at the school. Though Chappell has decades of experience in helping smooth the transition into school for students and families, she said it’s always tough for some kids. This year, she said, has been unlike any other.

“You’re asking me to start it at the beginning, you’re asking me to start in October, and you’re asking me to start again in January when they all come back,” Chappell said. “That’s three starts to a school year. That’s a lot for a teacher. You’re adding one little lump of new people now; you’re going to add another lump of new people later. That’s hard.”

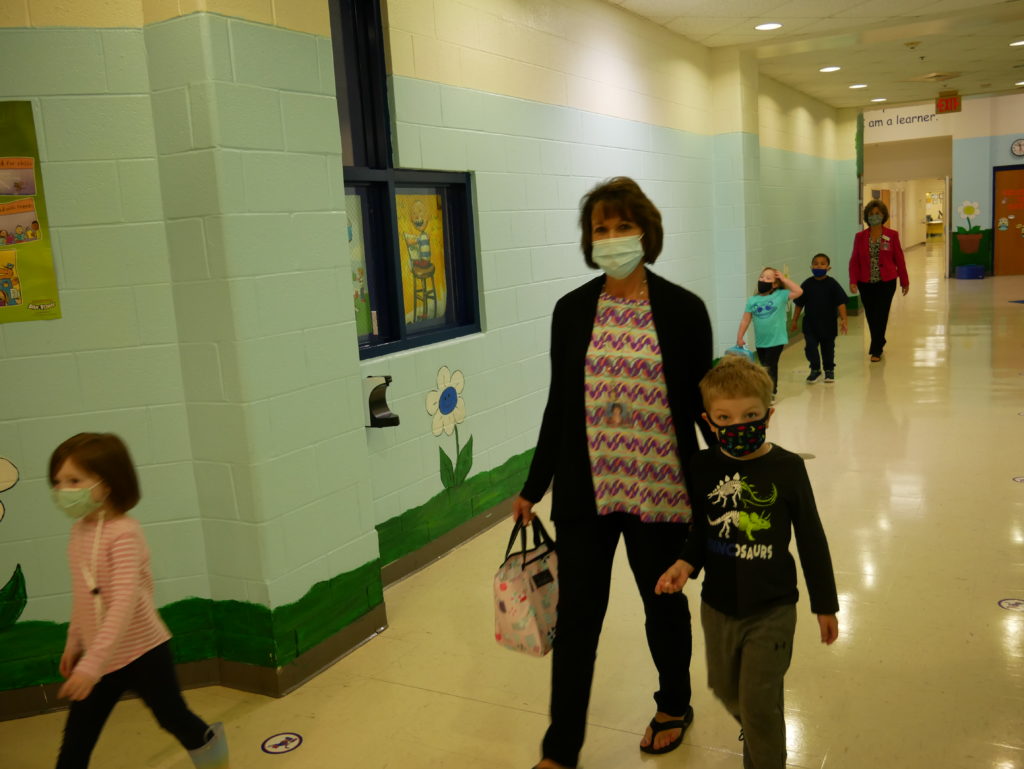

Lisa Chappell, a White Oak Elementary kindergarten teacher, walks her children back from lunch. Liz Bell/EducationNC

As kindergartners enter from different settings, some of whom have never been in a formal school environment, Chappell said yet another phase of adding new children felt impossible.

“You’re talking about all kinds of situations that they’re starting from,” she said.

Chappell said she felt she could be honest with Evans and said teachers have had input throughout district decisions this year. She chose to teach in-person this semester, for example.

“In anything we do here, we have a voice, for sure,” she said.

“The quicker you can isolate them… the quicker you can mitigate it.”

About 60% of children at both elementary schools go in-person every day of the week, and 40% are learning remotely. Starting in kindergarten, every child wears a mask for the entire day except lunch. Colored dots mark the floors for spread-out classroom and lunchroom lines.

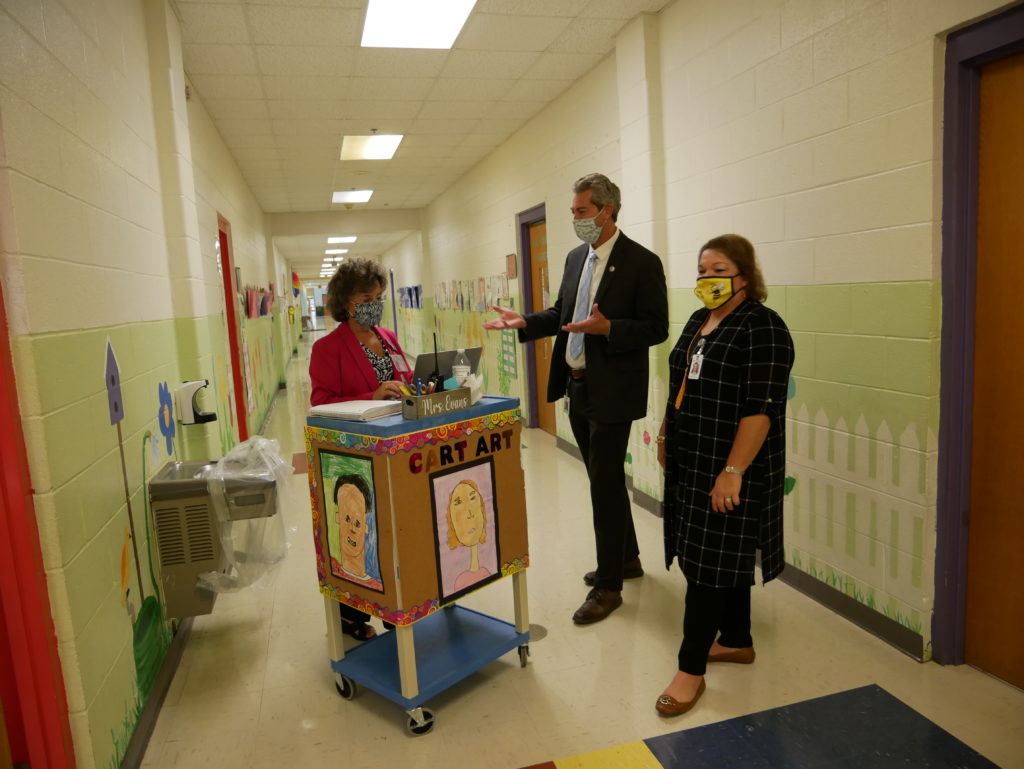

Throughout the hallways, there are hand sanitizer dispensers, signs with protocol reminders, and closed water fountains. Gym class is outside with more distance — to give students a break from wearing masks, and so the White Oak gym can be used for distanced eating.

Nurses at both schools have set up new isolation stations in case children display symptoms while at school.

“The quicker you can isolate them here in this area, the quicker you can mitigate it,” said Bonnie Lee, D. F. Walker’s school nurse.

So far, Sasscer said, there have been four cases at the two schools across both students and staff. Lee said there has been no spread at the schools, including on the bus.

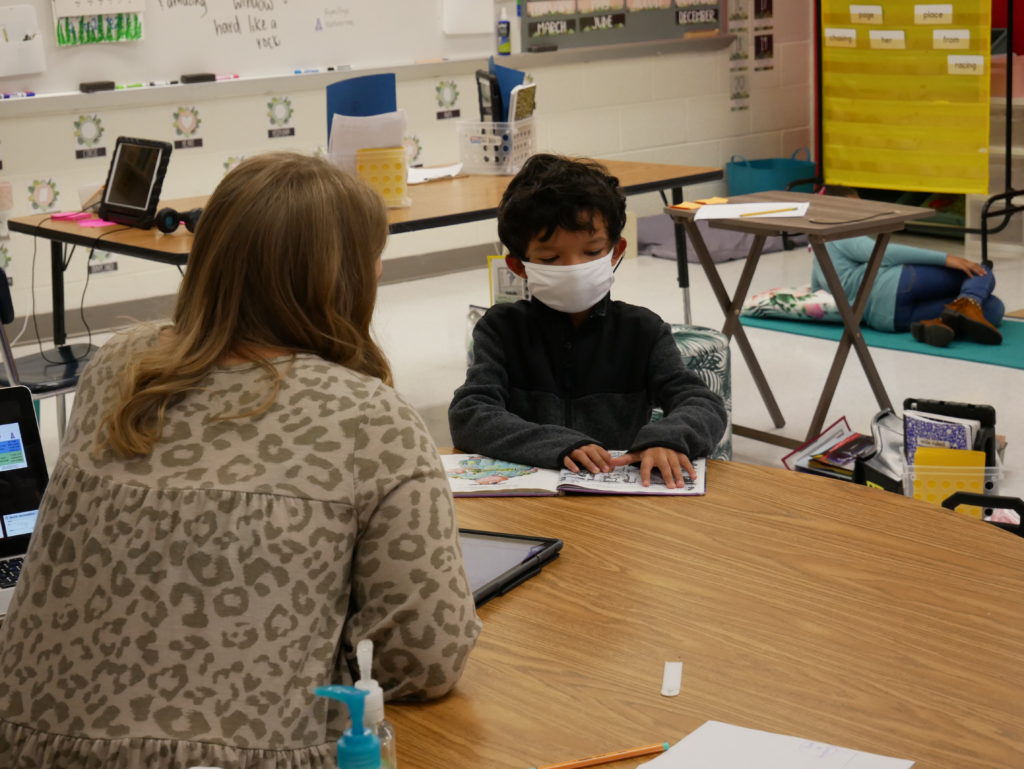

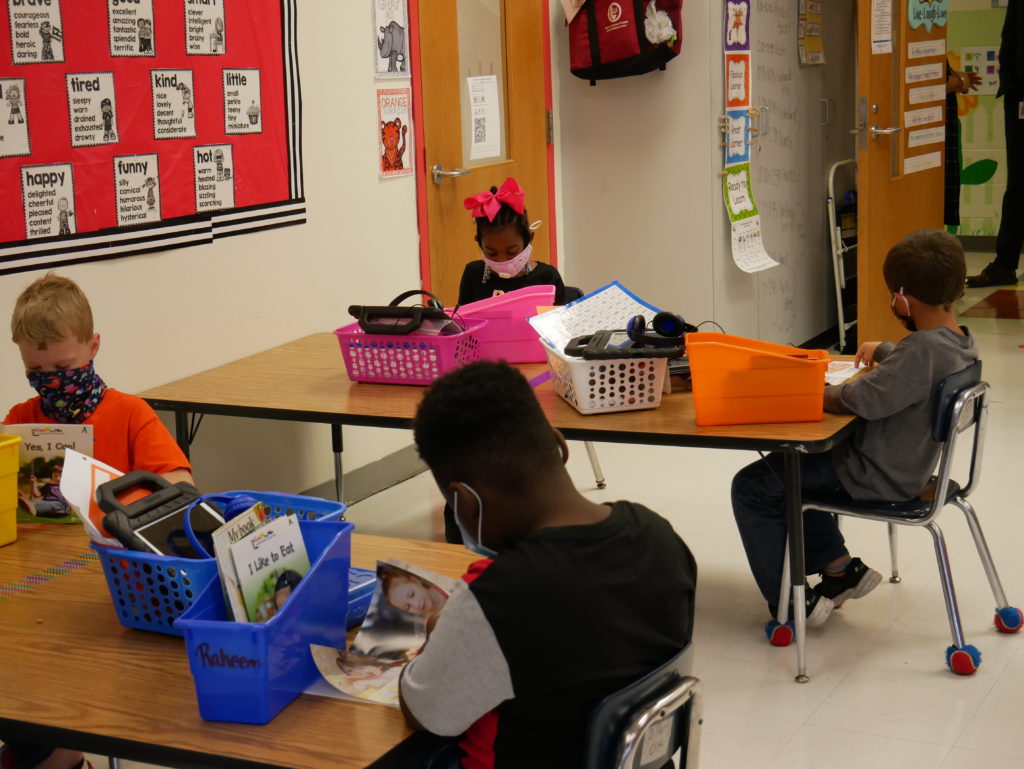

In-person classrooms have flexible seating that allows for six feet of distance between children. Teachers travel to desks for individualized instruction rather than multiple students going to meet the teacher at one table. Teachers sanitize desks and tables throughout the day.

One first-grade classroom was set up with a beach theme since regular classroom furniture has been rearranged for social distancing throughout the schools. Liz Bell/EducationNC

As guidance from state and national officials evolves, everyday operations must adapt. Evans said changes in mask-wearing guidance have caused recent frustration. She said the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used to define exposure as being within six feet of someone who tested positive, for at least 15 minutes, without wearing a mask. The guidance now has a note: “This is irrespective of whether the person with COVID-19 or the contact was wearing a mask…”

When Gov. Cooper said students older than 5 should be wearing masks, Evans said her pre-K teachers were concerned. Some students were turning 5 in their NC Pre-K classrooms, which operate under child care rules, and had not been wearing masks or social distancing.

“Are you going to have, like, one or two kids with a mask on and nobody else? How are you going to deal with that?” Evans said. “… You always get these frequently-asked questions after he speaks.”

Lee said that working closely with the local health department has been a life-saver for principals and nurses. When changes in guidance happen, she said, more clarity on what exactly changed would be helpful.

“If you’re not up to date each day, it could be different,” Lee said. “In the summer, before we were in school, we had a little bit more time to review it. But now in our case, with us here every day, it makes a big difference. We really have to be on top of it.”

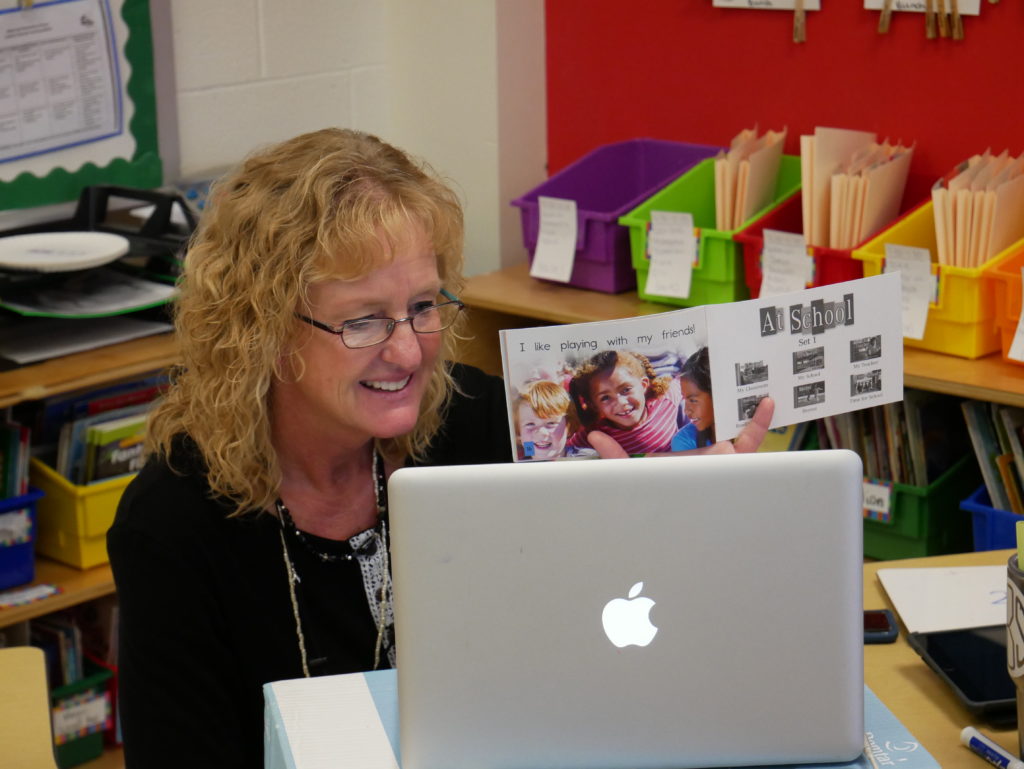

Walk by certain classrooms and you will find one or two teachers with only their laptops. Unlike in the spring, teachers are required to be in the building, even if they are teaching remotely.

“Overall, more kids are doing stuff now.

There’s always going to be that handful that aren’t.”

“Can everyone see my worksheet?” Octavia Shannon, a remote kindergarten teacher, asks her class of 5-year-olds through a computer screen.

Through equipment the district has had to buy this year, Shannon walks her students through a counting activity. Watch below as Shannon leads a Zoom of kindergartners.

Shannon is part of a group of elementary school teachers who have opted to teach remotely. In the mornings, since they don’t have children settling into their classrooms, they operate the drop-off and temperature-taking processes. The rest of that grade’s teachers record their live lessons, which the remote teachers post on the school’s online platform. They spend the rest of the day teaching remote learners via Zoom and communicating with parents and caregivers.

Sarah Girbach, a first-grade remote teacher, volunteered for the role because of her pregnancy. She said she’s glad she had the option and that the district has chosen to remain in plan B for now.

“We finally have gotten into the routine of things now, and so I didn’t really want to have to switch that up again,” Girbach said.

Her remote students are in a variety of settings, which requires extra coordination.

“I know it’s a lot on the families,” she said. “… Their kids are at day cares, or at grandma’s, so you’ve got to message the mom, and then the mom messages the other people, so it’s a lot of communication.”

Evans says hello to remote first-graders. Liz Bell/EducationNC

She said student participation is up from the spring. She said accountability is part of the reason; students won’t receive a “free pass” to the next grade.

“Overall, more kids are doing stuff now,” Girbach said. “There is always going to be that handful that aren’t.”

For that handful, “alternative plans” are still in the works. Evans said she is working on supports for students in difficult situations, like when a parent might lose a job if they stay home, or when a student is falling behind grade level.

“We’re going to ease back in to bring some families in that need to,” she said.