|

|

On a Saturday morning, before the coffee grew cold in the mugs of countless people beginning a day of leisure, the parking lot filled beyond capacity at Dillard Drive Magnet Middle School in Wake County.

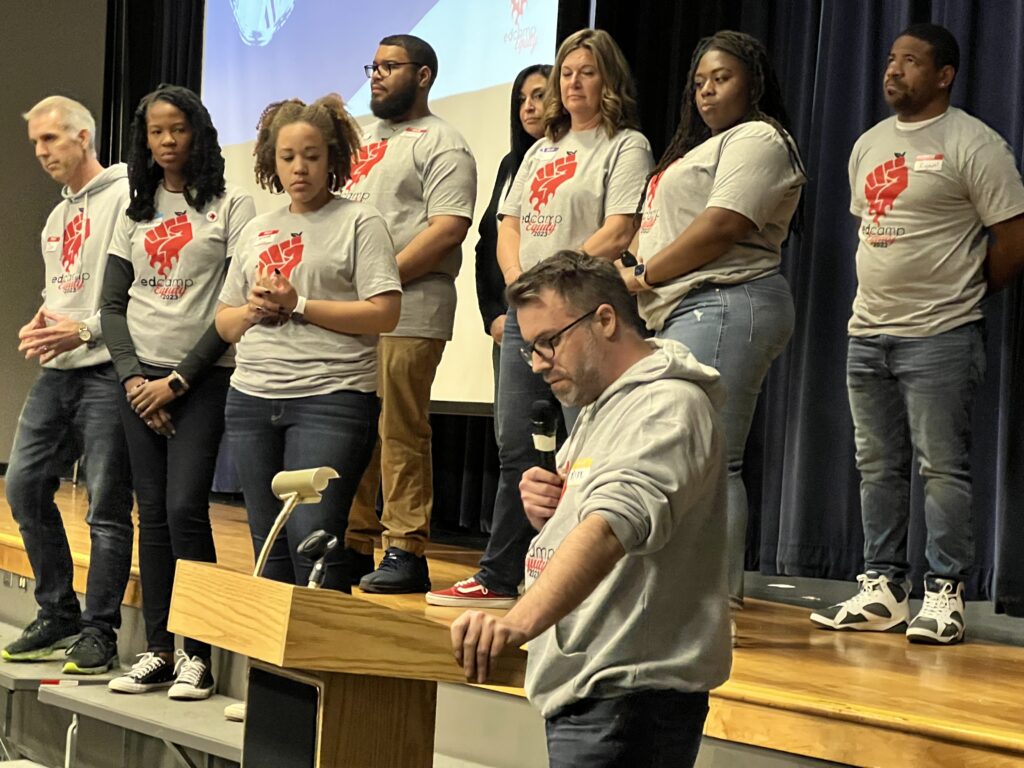

Teachers, administrators – educators of all roles, numbering in the 200s – filled the auditorium and halls for an event called EdCamp Equity.

EdCamp is a national model for convenings that is completely participant-driven and known as an “unconference.” A group of local educators organized EdCamp Equity using this unconference model and held the first gathering in 2018. Coming back together last month for the first time since the start of the pandemic, participants marveled at how much had changed and how much had stayed the same.

A number of “culture war” issues are prompting worry over the future of public education, with concern coming from as high up as the nation’s education secretary. The word “equity” has come under attack over these past three years.

“But this is a word we value and want to put in front of our community,” said Kristen McCollum, an assistant principal at Millbrook Elementary School and an organizer of the event.

Work worth sacrificing precious weekend hours

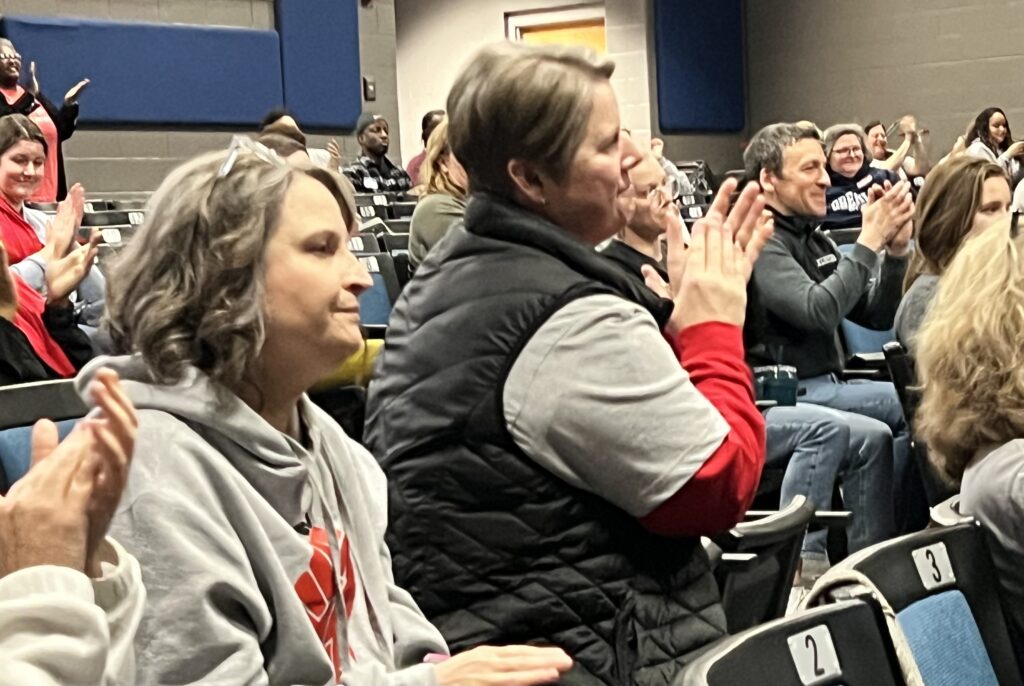

The teachers at EdCamp Equity spent five hours of their personal time on a weekend comforting and inspiring one another as they shared concerns about their students’ mental health, access to education, and preparation for their futures after school.

“It is my responsibility to grow myself so that I can grow my staff and we can grow our students,” said Wenita Merritt, principal at Carver Elementary School. “I don’t take my responsibility lightly. And I know that I have to continuously grow in my own understanding of practices in order to provide effective leadership.”

Just days prior to the convening, House Republicans had introduced a bill that would legislate how teachers in local schools can teach about race or sex. House Bill 187 is a reprisal of a bill that was passed but vetoed by the governor last session.

The revived legislation currently sits in the Senate Rules Committee after crossing over from the House and passing its first reading in the Senate. If it passes two more readings on the Senate floor, it goes to Gov. Roy Cooper for signature or, as expected, a veto.

House Bill 187 came up often at EdCamp Equity, with conversations focused on how educators will navigate the potential law for their students.

“Ultimately, I want them to get an education that will prepare them for the rest of their lives,” one participant said.

Educators worry bills will make the job harder

Joe Holt, Jr., who was the first Black student to challenge Raleigh’s segregated school system following the 1954 Brown v. Board decision, received an award at EdCamp Equity. He sat in some of the sessions prior to delivering a closing keynote address.

As he heard teachers speak, what stood out was their love for and desire to serve students. What also stood out was their concern about how legislation like HB 187, which proponents say is aimed at regulating teaching of divisive concepts, will impact teachers’ jobs.

“And it will make it harder,” he said. “And for what? What they’re teaching is not divisive… Somebody might get uncomfortable with that. But come on, what about the discomfort of being discriminated against, and being disenfranchised, and being denied your rights?”

Lindsay Mahaffey is a chair of the Wake County Board of Education. She was first confronted with the acronym CRT — Critical Race Theory — several years ago in an email written to her by a resident.

“CRT, what is that? And I thought they were talking about culturally responsive teaching, and I was like, ‘Yes, of course,’” she said, but then she started digging. And what she found, she said, was a lot of noise.

“It’s been interesting hearing all of these different versions of what CRT is versus what it actually is, and how it’s just exploded into this culture war talking point,” she said.

Participants commented on how many state bills aim to legislate what they can and cannot do locally as educators. They talked about how the job feels different as politics has focused more on their profession.

But, mostly, they spoke about celebrating equity – as a way to provide each student, regardless of race, gender, disability, or economic situation, what they need.

That means teaching them to read, write, and to do math, teachers said, but it also means giving students the tools they’ll need to understand and navigate the world in which they live. And it means recognizing that not every student comes to them with the same resources and opportunities, they said.

Sessions included analyzing data with an equity lens, inclusion for students with disabilities, inclusion for LGBTQ+ students, mental health stigmas among marginalized communities, and holding adults accountable for advancing equity.

Equity work isn’t new, and the need is ongoing

The challenges discussed were big and often beyond the sphere of influence for educators – but participants tried to focus on listening to one another and sharing solutions.

“Can we solve all of our problems today? Absolutely not,” said Terrence Hinnant, an organizer for the unconference and assistant principal at Zebulon Middle School. “… But we know that if we’re doing the work and we’re working hard, we’re going to try to make sure we move that ball up the hill a little bit more.”

A DJ, Douglas Curry, spun music in the lobby as participants danced and connected. Cell phones were out as educators traded numbers and grew their networks. After a day of talking about what educators wanted for their students, it was a fitting reminder that ultimately these participants used a personal day because promoting equity brings them joy, too.

“While many of us may be somewhat new to this work, the work is not new,” said Michael Parker West, an event organizer and assistant principal at Hortons Creek Elementary School.

“And it’s important that we know that from the day this country was founded there were those who worked, organized, and cajoled this country to live up to the values that we say we’re about. And that’s the work for all of us, to close the gap between our values and our actions.”