Daniel started third grade reading significantly below grade level, afraid of reading aloud and not able to make connections in the text.

His teacher, Jean Skelton, a third-grade teacher in Durham Public Schools, worked with him for hours to help him over his apprehensions. “I had to step him up slowly,” Skelton said last month. “He would whisper-read to himself or just mouth the words.”

After months of hard work, Skelton noticed that it was beginning to pay off. Daniel finished reading a third-grade level passage and had to answer the following questions: “What is the author’s purpose? Use evidence from the text to support your answer.” Skelton was delighted when he asked her for an extra piece of paper because he didn’t have room to fit all the details he had found on just one.

When he was finished, she looked over his work and was so impressed that she had him take it across the hall to another teacher.

“He ran back into my class and said, ‘She said this was really, really good! She said this was better than her example that she showed to her class! Is it better than her example, Ms. Skelton?” she said. “He shared his work with the whole class, and his peers told him how proud they were. He went home beaming that day – he got on the bus with just the biggest smile on his face.”

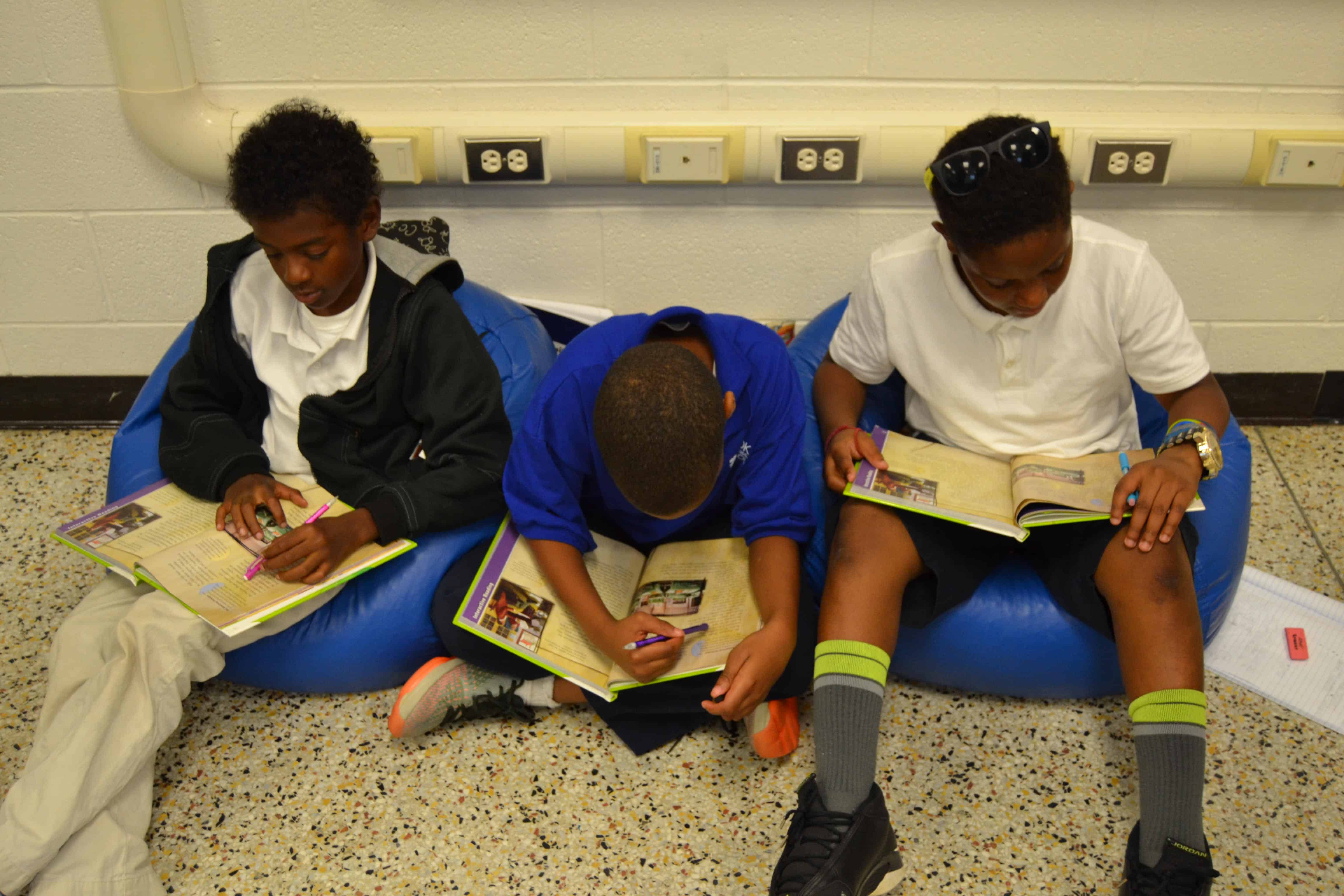

Students like Daniel, who start third grade behind in reading, are the reason for the national Campaign for Grade-Level Reading. The campaign is a community-based effort aimed at getting those kids ready for their breakthrough moment.

Third Grade as a turning-point

The Campaign for Grade-Level Reading identifies third grade as a key moment in a child’s reading development. But why?

“Research by the Annie E. Casey Foundation shows students who read on grade-level in third grade find greater academic success, and we have overall higher high school graduation rates later on,” said Libby Richards, Senior Community Programs Officer at Triangle Community Foundation.

“Third grade is really the turning point where you go from learning-to-read to reading-to-learn,” said Jaime Detzi, Chatham Education Foundation Director. “If a child can’t read sufficiently by third grade, every other item that is taught or presented to them after that point is hard to consume as knowledge.”

Eighty percent of low-income students and sixty percent of students nationwide are not proficient readers by the end of third grade. Because fourth grade marks this beginning of “reading to learn,” if they are not proficient readers then, they are prone to falling behind in all subjects, not just reading, which can lead to a lack of success later in life.

“Once they get into fourth grade, everything a student might be doing, whether it’s in history or in math, involves a certain level of reading to learn all of the new material,” said Lisa Finaldi, Community Engagement Leader at NC Early Childhood Foundation. “Grade-level reading by the end of third grade is a huge indicator of life success.”

The campaign’s goal

The nationwide campaign to improve third-grade literacy is about more than phonics or flash cards. It’s about providing the support systems that help kids learn — in particular, school readiness, attendance, and summer learning.

“It’s really a community-wide effort — it’s a collaborative effort through school districts, parents, and nonprofits recognizing that the work can’t be done through the schools alone,” Richards said. “The best way to ensure our kids meet their potential is to work together to solve this issue.”

School readiness means ensuring that students have access to high-quality early care and are healthy from birth to kindergarten, Richards said.

“Kids from low-income homes enter kindergarten having heard 30 million fewer words than their peers,” Richards said. “That’s a significant disadvantage right off the bat, and unless we work to close the opportunity gaps, this problem will continue to perpetuate itself.”

Learning to read and using literacy skills at a young age, when the brain is highly malleable, is crucial to childhood development.

“Every interaction is an opportunity to help grow a child’s brain,” Finaldi said. “The zero to eight (years-old) period is really when your brain is doing most of its building.”

The second pillar is based on boosting school attendance. Chronic absence, or missing 10 percent or more of the school year, affects students from low-income homes at a much higher rate than their peers, according to Richards.

“The absences can come from parents’ inability to get their kid to school because of things like transportation issues, the health of the child due to unforeseen circumstances, family hardship, and more,” Richards said.

The final pillar is based around summer learning. “Making sure that everybody has access to educational opportunities during the summer vacation — whether that’s just having books in their home, going to a summer camp, or visiting museums,” Richards said.

The Campaign on a local level

Triangle Community Foundation is supporting the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading by providing grants and technical assistance to the local nonprofits running campaigns in Wake, Orange, Durham, and Chatham counties, Richards said. The Foundation will provide $50,000 per year for the next three years to each campaign. As a part of this investment, the Foundation has partnered with United Way of the Greater Triangle to make a bigger difference. Through this partnership, they are leveraging resources to make a regional impact on literacy by supporting the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation, the state lead for the campaign. By working together to affect change in literacy for our students, the they are also hoping to grow support among other regionally-minded funders.

“Triangle Community Foundation is supporting the communities’ ability to do the work,” Finaldi said. “The Triangle-area communities are coming together to create a plan to change the trajectory for children.”

Chatham Reads is one of those organizations aiming to increase literacy rates. It installs “Book Baskets” at restaurants, doctor’s offices and other places children are often waiting and have free time to read and created the Books on Break book drive program to help prevent summer learning loss.

It held summer book drives at two high-poverty elementary schools last year, Detzi said. At first, she said, the students didn’t understand they got to keep the books forever. Two-thirds of students living in poverty don’t have a single book at home, she said.

“I said ‘Yes! They live in your house, these are your books,’” Detzi said. “It was one of the sweetest moments just to be able to see how excited a child could be just by getting a book.”