Share this story

|

|

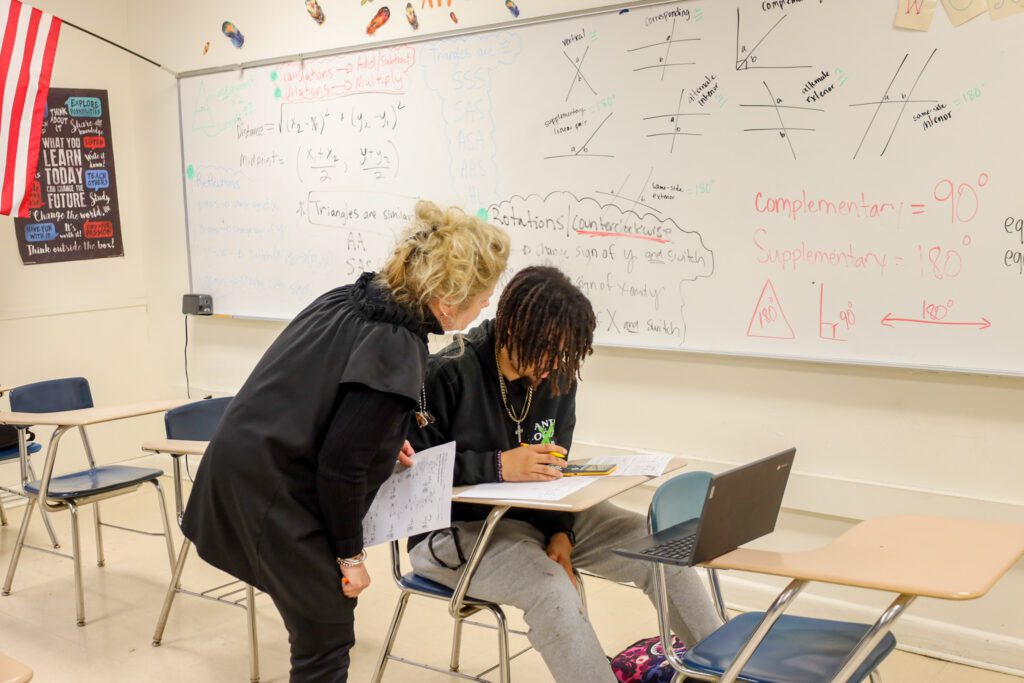

Sabrina Reeves is the Clinton High School (CHS) 2022-2023 teacher of the year.

She’s a co-chair for the prom committee and chair for the Miss Clinton High School pageant.

She serves on the School Improvement Team and as the advisor for the Fellowship of Christian Students.

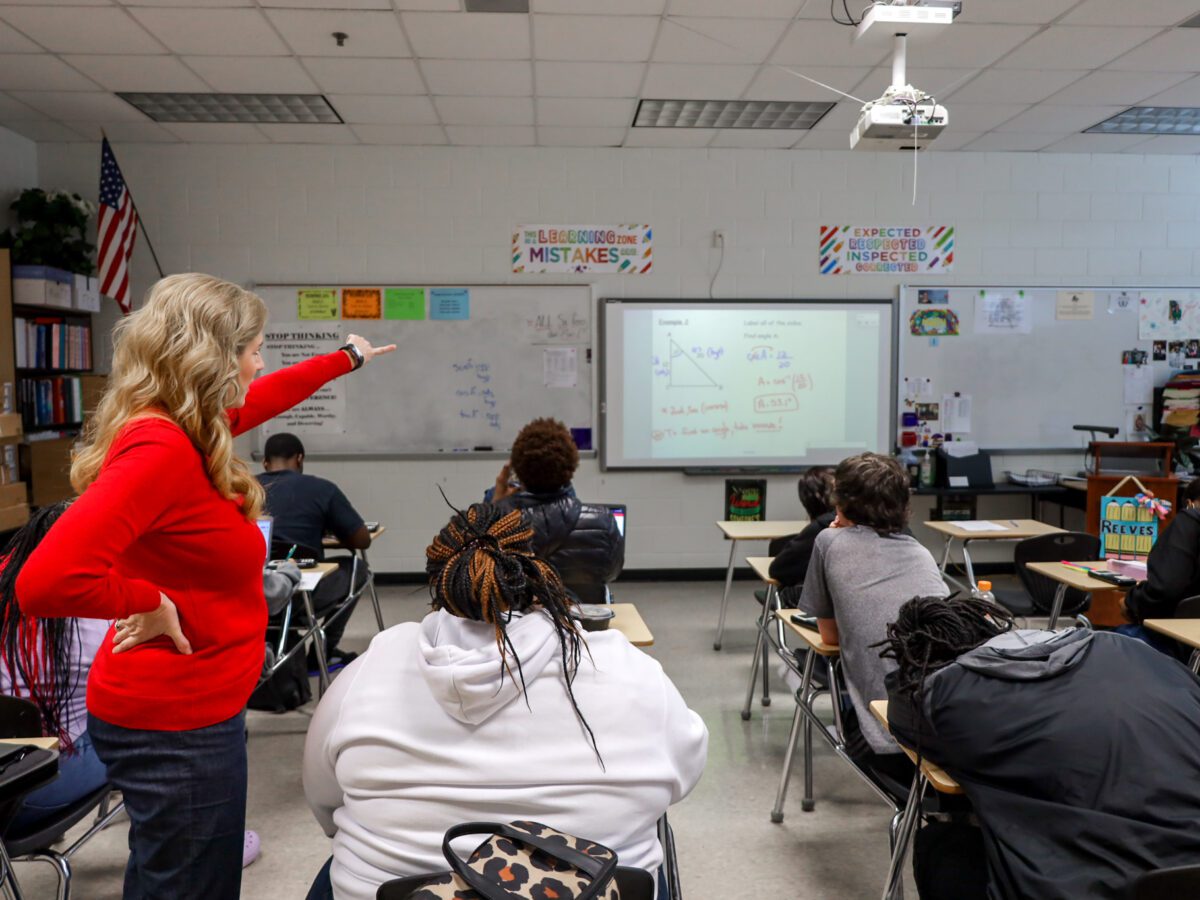

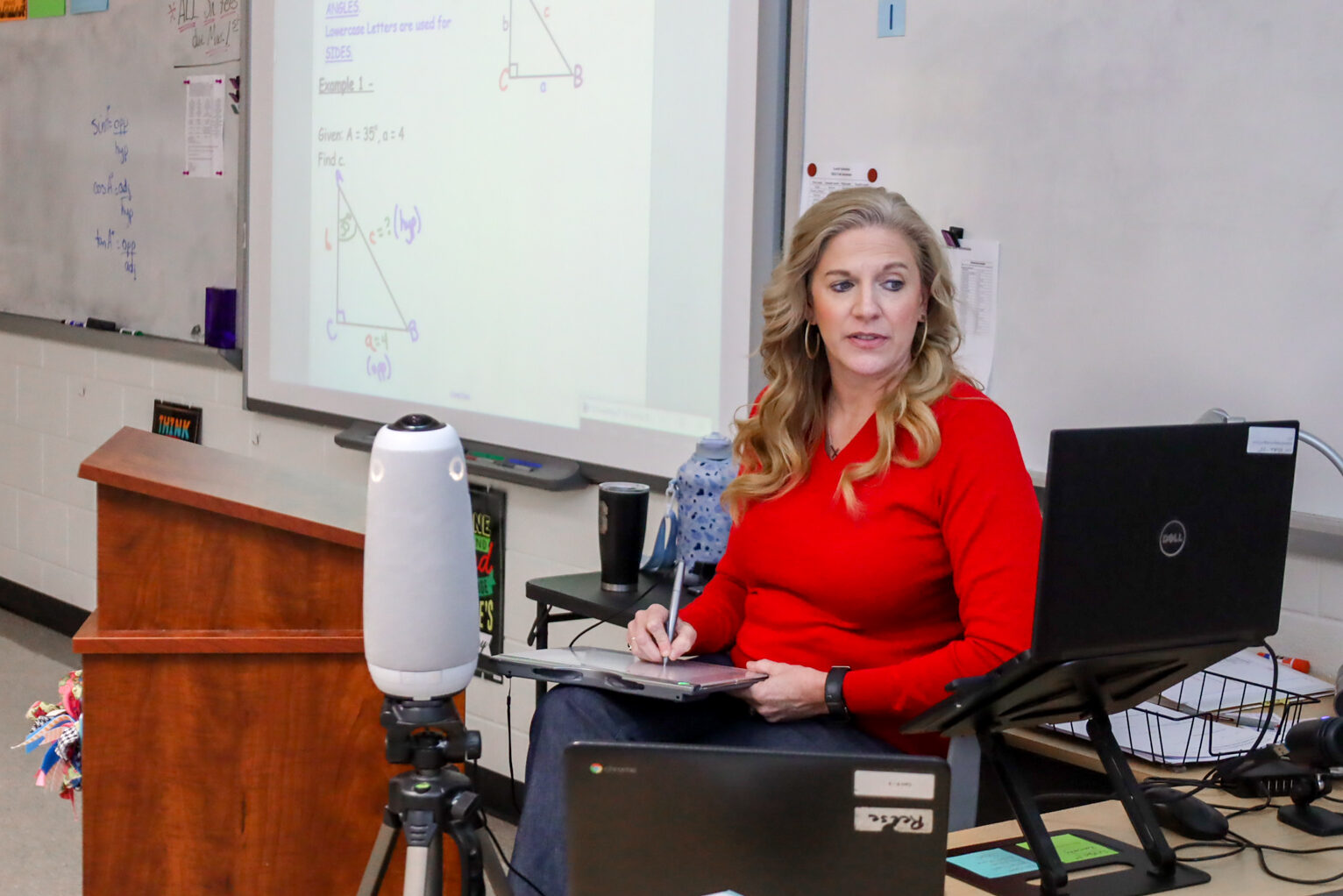

And since August 2022, Reeves has been remotely teaching Math IV classes to students at John A. Holmes High School (JAHHS) in Edenton 150 miles away – while simultaneously teaching students in her classroom at CHS.

Finding ways to tackle the teacher shortage

As the 2022-2023 school year drew close, Dr. Michael Sasscer knew he needed to find a qualified teacher to teach Math IV at JAHHS, rather than hiring a long-term substitute teacher to fill the vacancy. Sasscer, Edenton-Chowan Public Schools‘ superintendent, said it became apparent he needed to look “across district lines.”

“If we can work with teachers synchronously, we’re no longer bound geographically,” Sasscer said. “And if we have somebody who’s excellent and willing to work with more kids and build a relationship from afar, then we could give access to high-quality teachers.”

After talking with Sasscer at a conference, Dr. Wesley Johnson, Clinton City Schools superintendent, was immediately ready to join. He realized Sasscer’s vision, that this instructional model could benefit students in both districts, and create a model that other districts could follow.

Determining which CHS math teacher would take on the task may have been the simplest part of implementing the model; Reeves is the only Math IV teacher at CHS. Johnson said Reeves stepped up and took “over the show” immediately.

“Sabrina will do anything you ask her to do. Of course, there was some nervous energy at the beginning,” Johnson said. “But, she has exceeded all of our expectations.”

Preparing for simultaneous remote and in-person learning

Reeves has been teaching math for over 20 years, but more than her years of experience, she said it was remote learning during COVID-19 that prepared her for this innovative instruction model.

“We actually got a new curriculum the year we were shut down for COVID when we were in remote learning,” Reeves said. “That’s where I learned a lot of what I’m actually doing and utilizing now for the hybrid class.”

When Johnson approached her with the idea shortly before the school year started, Reeves was willing but wanted to be prepared.

“I basically sent a list of about 15 or 20 questions and said, ‘Hey, these are questions I need answered,’” Reeves said.

Reeves wanted to know who her point of contact would be at JAHHS, how she would key in JAHHS student grades, and more. Largely though, Reeves was concerned about the logistics and technology needed.

Kerry Mebane, chief technology officer at Edenton-Chowan Public Schools, said configuring the technology at JAHHS was a simple task – and one that the district was already prepared for.

Edenton-Chowan Public Schools has high-speed internet, uses Google Classroom, and is a one-to-one school – meaning every student has a device. With these pieces of technology in place, Mebane said the technology was set.

“In any kind of instructional setting, you better yourself every semester, every year. But the technology pieces were quite simple,” Mebane said.

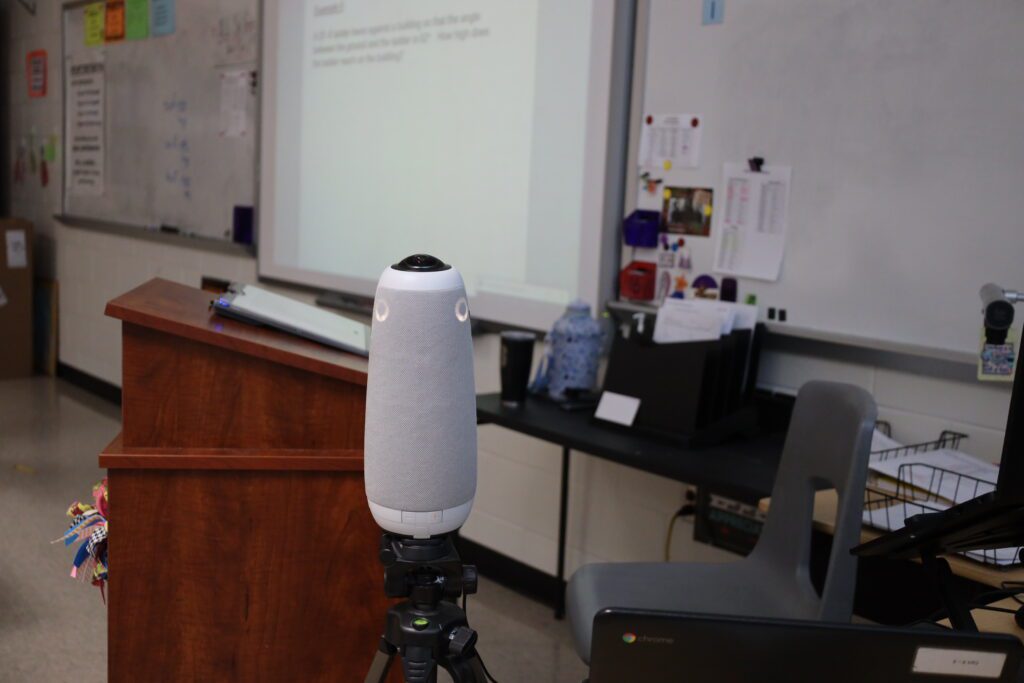

There have been a few tweaks since the first semester. In the fall, each student wore earbuds or headphones to tune into Reeves’ lecture on their devices. After a few hiccups with that system, the two school districts found a piece of technology that has been a game changer: the meeting owl. This 360-degree camera follows Reeves around her classroom during instruction and allows students at JAHHS to ask questions in real time.

How does instruction look?

In some ways, instruction hasn’t changed for Reeves or her students. CHS students come into class as usual and settle in for the 90-minute class. About three hours away, JAHHS students come into the classroom and log into Google Meet to prepare for the same class.

“Use your chat and tell me what you think the answer is,” Reeves says after putting a problem on the board.

Each day, Reeves logs into Google Meet and begins instruction. Throughout the class, JAHHS students are able to verbally ask Reeves questions or drop a question in the chat box. JAHHS employs an online facilitator, Shirley Powell, who is in class with students every day. Reeves shares her solutions key with Powell, who is a retired math teacher. Powell can answer questions for JAHHS students during class.

Powell said students in the class work hard and feel comfortable asking questions. Nearly all students in Math IV this semester have an A or B in the class.

“This is successful,” Powell said.

Rinehart said having Powell in the class is essential to the success of the model. Instead of having no teacher in the classroom, she said students really end up with two.

“You do have a teacher. You actually have two,” Rinehart said.

Both districts use Google Classroom as their digital learning platform, so Reeves is able to copy all of her classwork, lessons, and instructional materials for students from both districts.

Reeves wants students at CHS to get to know students at JAHHS, so she incorporates group work. Students from each district log into Google Meet, are divided into breakout rooms, and collaborate on classwork together.

Being adaptable to create the best system

Shirley Rinehart, JAHHS’s principal, said she didn’t fully buy into the idea at first, but trusted Sasscer’s leadership.

“I wanted the ideal face-to-face teacher in that classroom,” Rinehart said. “I was just always reminded to have an open mind and try.”

Rinehart said the model is about being “proactive” instead of “reactive” – something that everyone had to remember early on.

In the fall, the districts spent time working out kinks in the model.

JAHHS offered two sections of Math IV in the fall semester, while Clinton only offered one. Instead of being able to teach the second class live, Reeves uploaded videos of herself teaching the lessons. But she noticed inconsistencies in student performance.

Because CHS’s school day ends about 30 minutes before JAHHS’s, Reeves began logging into Google Meet — a video communication platform — at the end of the day to offer live help to that class instead.

“That shows the passion,” Rinehart said. “For somebody to take it upon themselves to go above and beyond.”

When the spring semester started, the two districts realized that the Math IV sections didn’t line up. Rinehart changed the master schedule at JAHHS to ensure that the sections lined up and that students had live access to Reeves.

Reeves thought getting in-person interaction with students at JAHHS was important to help them build connections. She’s made a few visits to the high school already – once to prep for exams with her first-semester students, and another time to meet her second-semester students.

Sasscer said that creating relationships is what drives the success of this model.

“That’s a testament to her seeing the vision, running with the vision, and doing the best and making it beneficial for each student that she’s serving,” Sasscer said. “At the end of the day, what benefits this model is the relationship.”

Sustaining this model

Asking Reeves to teach additional courses was a big ask from both districts – and one she has been compensated for. Edenton-Chowan Public Schools used Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds to provide Reeves with a $9,000 stipend per section she teaches.

But, how will they continue this model when these funds run out?

Sasscer said he’ll continue exploring alternative funding options to grow and sustain the model. He believes that allowing flexibility with position allotments could be a way to “creatively” fund advanced teaching roles.

“One of our desired outcomes is for the General Assembly to consider a reform of fiscal policy that would allow position allotments to be converted to dollars to pay for these stipends,” Sasscer said. “There’s the wonderful, feel-good of meeting the teacher shortage, and that’s all a part of this, but then there’s a bigger picture of what this could mean for innovation and sustainability if we do have shortages for a greater period of time.”

As the State Board of Education continues to consider teacher licensure and pay reform, Sasser says this model could be considered an advanced teaching role.

According to the North Carolina Department of Instruction, teacher vacancies have increased from previous years. In the 2021-22 school year, there were 5,091.46 instructional vacancies on the 40th day of school.

Knowing this, Johnson said sustaining this model is imperative.

“We see it as a necessity. We’re going to be dealing with teacher shortages, if you believe the research, for years and years to come,” Johnson said. “If we could get some additional LEAs to buy into this innovative approach, I think we can go a long ways and help a lot of children.”