The Rev. Lorenzo Lynch dressed as if he was going to church. It was a hot September weekday when he visited his former schoolhouse in the Martin County town of Hamilton. The old schoolhouse was dusty and strewn with debris from years of disuse.

But the Rev. Lynch felt it was appropriate to wear a suit and tie to honor his childhood school. His outfit, he said, also was a way of paying respect to his forebears, his teachers, and a life of learning that began at this school.

As a child, the Rev. Lynch missed an entire year of school at Hamilton. It was the depths of the Great Depression, and his family couldn’t provide clothes for him to wear to school. So young Lorenzo stayed home, where his mother taught him. She got her early education at a similar school in a neighboring county.

The segregated schools they attended were among nearly 800 built throughout rural North Carolina beginning in the 1920s. Nearly 5,000 similar schools were constructed in 15 states, from Maryland to Texas, with North Carolina having the most. Today we know them as Rosenwald Schools.

The name honors the modest Chicago business executive and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck & Co. in the early 20th century. The son of Jewish immigrants from Germany, born and raised in Springfield, Illinois, Rosenwald never finished high school.

Rosenwald met Booker T. Washington in 1911 when the former slave and president of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute visited Chicago. The men struck up an immediate friendship, and Rosenwald was invited to join Tuskegee’s board of directors.

Young African-American students at Tuskegee demonstrated their proficiency at higher education in addition to learning trades. The latter was part of Washington’s strategy of convincing the Jim Crow South to provide schools for black children, but it was slow going.

Washington told Rosenwald that the South needed decent elementary schools for rural African Americans. Public funding, especially in rural areas, was almost nonexistent. Black communities hungered for schools, Washington said.

Would Rosenwald help fund an experiment to test this theory? The businessman agreed to help build six schoolhouses in rural Alabama. Students flocked to the schools and thrived. The pilot proved so successful that Rosenwald launched a fund to support building schools throughout the South.

The plan Rosenwald engineered foreshadowed the matching grant programs of today. The fund typically provided just a fraction of the money necessary to construct a school, perhaps 25 percent or less. The local school board (controlled by whites) was required to provide funds. The black community to be served had to raise money, and white citizens also contributed in some cases.

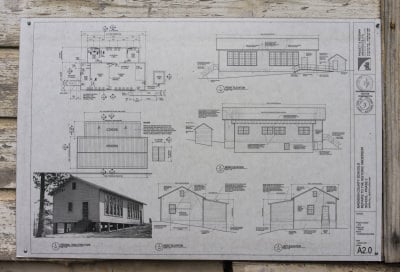

A church or farmer usually donated land. Local craftsmen, using plans provided by the fund, built the schools. Teachers’ salaries came from other sources.

Thanks to Rosenwald Fund records now housed at Fisk University, we know how much each school cost and the source of every dollar.

The Hamilton school, attended by young Lorenzo Lynch, opened around 1921. The total cost of the “three-teacher school” was $4,500. The Rosenwald Fund provided $1,000. Public (school board) funds totaled $3,000. “Negroes,” according to the records, donated $500.

The Hamilton Rosenwald School now belongs to Roanoke River Partners, a regional, nonprofit economic development organization. The school is being restored to serve as an interpretive site to tell the Rosenwald story, a community gathering place, and a river center. A landing on the Roanoke River is a short walk from the school.

The National Trust for Historical Preservation estimates that, by 1928, one-in-every-five schools for blacks in the rural South was a Rosenwald School. The program’s statistics remain staggering today.

- Schools built: 4,977, plus 217 teachers’ homes and 163 shop buildings.

- Students served: 663,615.

- Total cost: $28,408,520.

The program came to an end in 1932, the year of Rosenwald’s death. Most of the schools remained in service until the end of segregation, and the last alumni are nearing retirement age. Several hundred school buildings survive. Some are falling down, while others still serve as public schools or daycare centers. A growing number have been restored and given new life as community centers. Alumni and friends in communities from Maryland to Texas are joining forces to preserve their schools and honor their legacy.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, who have studied Rosenwald Schools, say the schools’ benefits have rippled through the generations, benefitting not only alumni but their offspring and the nation.

That comes as no surprise to the Rev. Lorenzo Lynch. In June, he stood on a stage with President Barack Obama as his daughter, Loretta Lynch, was sworn in as attorney general of the United States.

Watch this video about Longleaf Production’s forthcoming documentary on the history of the Rosenwald Schools: