|

|

This article is part of a book by EdNC titled, “North Carolina’s Choice: Why our public schools matter.” Here is a free PDF of the book. A printed copy can be ordered here.

Learning doesn’t start at age five, and it doesn’t start in school.

Imagine the parent you might see shopping at your nearest big-box store, pushing a toddler in their cart, narrating their actions.

That toddler is taking in everything, associating new words with new objects through a combination of looking, listening, and asking an endless stream of questions.

The parent and child are learning together.

And this type of learning — the learning that happens before the age of five — is critical for brain development.

The vast majority of human brain development occurs in the first three years of life. During this time more than 1 million neural connections are formed each second. Strengthening these connections during the 2,000 days between birth and kindergarten leads to improved outcomes in education, health, employment, and economic stability.

While learning doesn’t begin at age five, formal public education typically does. But in North Carolina, public schools provide essential services to children and families well before they enter a kindergarten classroom.

The goals of public kindergarten and preschool

The idea for kindergarten came from a 19th century theory that young children were not just miniature adults who simply hadn’t had the experiences necessary to function as full-sized adults, but that their brains were in a stage of development that would benefit from a nurturing environment that encouraged curiosity and play.

The first kindergarten was established in Germany in 1837. By the mid-1800s, German immigrants brought kindergartens to the United States, and a century later they were commonplace in public school systems across the nation.

The path to public kindergarten in North Carolina is described in a 1974 DPI report. In the report, the researchers outline the history of formalized early childhood education.

As early as the 1830s, private interests had been operating what were then called “Infant Schools.” According to the DPI report, “Some advertised themselves as being places to prepare children for later schooling; others simply promised to keep children out of mischief.”

Some of the state’s earliest kindergartens were established by mill owners for the children of millworkers: “When both father and mother were employed by a mill, this presented the only alternative to leaving their young children unattended.” Kindergartens were also established by educational institutions that were training future teachers.

In the first decade of the 20th century, free public kindergartens were introduced in Buncombe County and Washington County, though both programs were short-lived. In the following two decades, parents and teachers joined forces to push for access to public kindergarten statewide. Their efforts brought continued attention to the need to educate young children.

By the mid-20th century, private kindergartens were popping up around the state in churches and homes. They fell under the supervision of DPI thanks to a 1945 law affirming the department’s authority to do so. Parental demand for their children to attend these private kindergartens was high, which drove up the price but not the supply.

Parents and teachers continued their push for free public kindergarten, and bills to provide it were introduced in the General Assembly in 1963, 1965, and 1967 before one finally passed in 1969.

Districts were invited to apply for the opportunity to offer free public kindergarten during the pilot phase of implementation. The stated objectives of the kindergarten pilot were:

- To provide many opportunities for social development and adjustment to group living;

- To promote development of good health habits;

- To instill habits, appreciations, and attitudes which serve as standards of conduct at work and play and as guides to worthwhile use of time and materials in and out of school;

- To provide opportunity for self-expression through language, music, art, and self-experience;

- To provide situations in which children can succeed and through success, build confidence in their own ability and work;

- To develop an atmosphere in which creativity is stimulated;

- To develop a feeling of adequacy through emphasis on independence and good work habits; and

- To lay foundations for subject-matter learning and intellectual growth.

North Carolina fully implemented public kindergarten statewide by the 1977-78 school year.

As experts learned more and more about how brains develop throughout the 20th century — and came to understand the crucial development that occurs in the 2,000 days leading up to kindergarten — there was increased interest in extending the benefits of public education to younger children.

It took 140 years for kindergarten to move from being an idea to being a regular part of our state’s public education system. In the 45 years since, public preschool has followed its own path.

During those decades, demand for early childhood care and education had not been met by the private market — a market that economists generally define as “failed.”

As a result, North Carolina has developed a variety of public investments to support families seeking to enroll young children in preschool, including Smart Start and a first-in-the-nation quality rating and improvement system. Dozens of states followed our lead, and by the end of the 20th century, North Carolina’s reputation as an innovator in early childhood education was well-earned.

In 2001, North Carolina started More at Four, a statewide (though not universal) public preschool program. Here’s how it was described in a 2005 program evaluation conducted by the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute:

The North Carolina More at Four Pre-kindergarten Program is a state-funded initiative for at-risk 4-year-olds, designed to help them be more successful when they enter elementary school. More at Four is based on the premise that all children can learn if given the opportunity, but at-risk children have not been given the same level of opportunity.

In 2011, More at Four was renamed the “North Carolina Prekindergarten Program,” typically referred to as N.C. Pre-K.

And N.C. Pre-K is working. Numerous studies over the past two decades have found positive, lasting impacts for children enrolled in our state’s public preschool and for their families.

In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services reported that 90% of N.C. Pre-K participants were from low-income backgrounds, despite the requirement being just 80%. DHHS also reported the program had positive effects on children’s language development and communication skills, cognitive development, and emotional and social development. This impact wasn’t limited to enrolled children and their families:

… Studies have consistently shown lasting positive impacts for the children involved, the classrooms and communities they are a part of, and then as a result, for the school systems these children attend and their families and the State of N.C. as a whole.

The authors of the report noted that one reason for these spillover benefits is that N.C. Pre-K funds are commonly blended with other funding sources, creating classrooms where students who aren’t enrolled in N.C. Pre-K still benefit from the program.

Additionally, a 2018 report on potential expansion of N.C. Pre-K stated, “Extensive research has confirmed that children who participate in the program experience significant positive outcomes that extend well into their elementary school years.”

The role of public schools in preschool

Today, N.C. Pre-K is a statewide preschool program designed to support low-income 4-year-olds at risk of negative education outcomes. It is housed under the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) at the DHHS.

N.C. Pre-K is managed locally by 91 contractors, most representing one or two counties. Contractors can be one of the state’s school districts, regional Smart Start agencies, or Child Care Resource & Referral Councils.

Regardless of the type of contractor, classrooms can have a maximum enrollment of 18 students and must provide breakfast or a morning snack, plus lunch that meets U.S. Department of Agriculture requirements. Each classroom must have a lead teacher who has or is working toward a K-12 teaching license, plus an assistant teacher who has or is working toward an associate degree in early childhood education, or a child development credential.

A 2018 report from the National Institute for Early Education Research explains the N.C. Pre-K management structure this way:

Contractors incur the administrative costs of the program, including monitoring, recruitment, assignment and payment. The contractors then subcontract with “providers” at individual sites, including for-profit and nonprofit private centers, public schools, and Head Start agencies. These N.C. Pre-K providers incur the costs of day-to-day operations of the program.

Because N.C. Pre-K is designed to be classroom-based, public schools are a natural fit as providers. Sometimes, even when Head Start or private centers are providers, they will still operate from public school classrooms or campuses. That’s partially because state funds provided for N.C. Pre-K can only be used in very specific ways:

State funds are to be used for ‘operating’ the N.C. Pre-K classrooms, which may include salary and/or benefits for teaching staff, equipment, supplies, curriculum and related materials, developmental screening tools and assessments efforts, and staff training. Funding can also be used to cover expenses associated with meeting the program’s quality standards. However, state funding is not available to cover certain costs — primarily the costs of real property, buses, or motor vehicles.

Public school districts already have the “real property” needed to provide N.C. Pre-K, namely classrooms. And many also allow N.C. Pre-K students to ride school buses.

Due in part to these specific requirements, DCDEE’s most recent data reveal that more than half of N.C. Pre-K classrooms are operated by public schools. According to self-reported data provided by DPI’s Office of Early Learning and DCDEE in July 2023:

- At least 622 public schools are home to at least 1,102 NC Pre-K classrooms.

- Approximately 2,032 preschool classrooms are operated by public schools, regardless of funding source.

- Approximately 73 of 115 school districts offer services for children under age 5, independent of N.C. Pre-K.

- School districts provide itinerant exceptional children services to over 5,400 preschool children statewide.

One major advantage of an N.C. Pre-K classroom located in a school building is its proximity to the services that school districts provide, particularly for children with learning differences. The earlier that schools learn about the special needs of incoming students, the better prepared they can be to support their education. That’s part of why schools play such a crucial role in helping families identify learning differences in the first 2,000 days.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, “The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a law that makes available a free appropriate public education to eligible children with disabilities throughout the nation and ensures special education and related services to those children.”

For the purposes of early childhood education, there are two relevant parts of IDEA to know about:

- Part C relates to services and support for children from birth to age three, providing for the creation and execution of individualized family service plans (IFSPs). In North Carolina, this part is administered by the DHHS.

- Part B relates to services and support for students ages three to 21, providing for the creation and execution of individualized education plans (IEPs). In North Carolina, this part is administered by the DPI.

This means that school districts are responsible for providing special education to students as young as three. But for families with children who have IFSPs, school districts actually start the process of evaluating what their IEP needs will be at age two. For families without IFSPs who suspect their children might have special needs at age three or four, schools do those evaluations for free to develop IEPs as needed.

In the 2022-23 school year, public school districts served 16,344 children ages three to five before they reached kindergarten. That’s 9% of the total number of students they served through IDEA.

Losing public preschools: ‘It would be devastating’

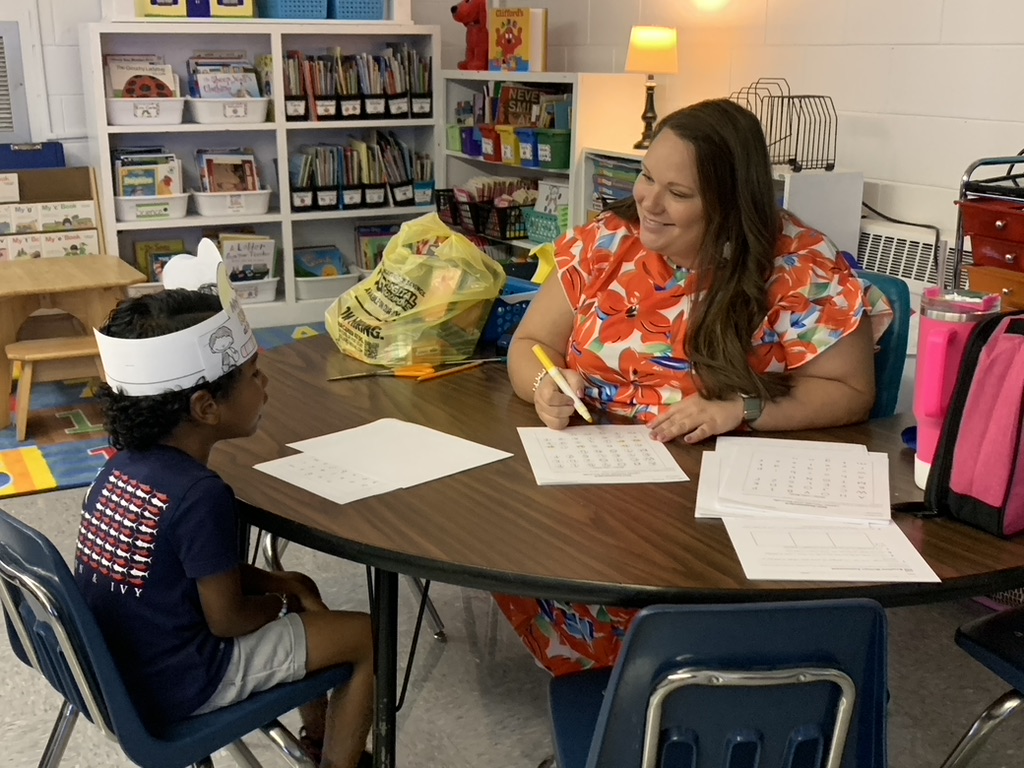

To learn more about the role of public schools in educating our state’s youngest learners, EdNC reached out to every N.C. Pre-K contractor, interviewing more than half of them during the summer of 2023 by phone or email.

We learned that in Brunswick, Camden, and Stanly counties, there are no longer any N.C. Pre-K classrooms on public school campuses. While these counties are in very different parts of the state, their explanations for why public schools quit hosting N.C. Pre-K were the same.

“Our schools were just busting at the seams, and they needed to use those classrooms or that space,” said Jake Griffiths, the Brunswick County N.C. Pre-K contact.

Chudney Hill-Gregory, the contact for Camden County, described the population increase in Camden County putting pressure on public school classrooms, saying schools still want to host sites but simply don’t have the space.

“We did have the problem of space a few years ago… and our county lost several classrooms at that time,” wrote Terri Scott, the contact for Stanly County’s N.C. Pre-K contractor.

This points to the need for greater investment in both North Carolina’s public schools and our public preschool program as the state’s population continues to grow. But what’s truly telling is what happened to early childhood education in these counties when public schools were no longer able to share their space.

“I know that we served a lot more children when it was in public schools,” Griffiths said. “So we pretty much cut that in half or even a third.”

“It has given one less option for families to receive services at that location/area of the county,” Scott wrote of Stanly County. “It creates a hardship if families need transportation within that school’s district to the school where their other children attend in a K-5 setting.”

In counties where public schools don’t host N.C. Pre-K classrooms, families have fewer choices about where to send their children for preschool. Their freedom to live and work in a location of their choosing is limited by the lack of access to early childhood education.

If we didn’t have pre-K, if we couldn’t get them in these programs, kindergarten wouldn’t be kindergarten.

Bobbi Holly, Bertie County

While population increases caused classroom closures in these three counties, decreases in student population can have the same outcome. If students leave public schools, schools could close or consolidate. That would similarly reduce the number of classrooms available for N.C. Pre-K.

When asked to imagine what would happen in their communities without N.C. Pre-K in public schools, here’s what contractors had to say:

- “Well, it would be catastrophic. It’d be catastrophic.” – Stacey Bailey, Buncombe County

- “Our community would be devastated, and that is not an exaggeration.” – Rebecca Snurr, Transylvania County

- “If the public schools were to stop serving NC Pre-K students, it would be detrimental to our county.” – Sharon Lyons, Alleghany County

Almost a quarter of respondents used the words “catastrophic,” “devastating,” or “detrimental.” And in cases when they didn’t rely on those specific words, they still described potentially devastating impacts: children becoming food insecure or losing access to health screenings, parents quitting work or stopping out from postsecondary education.

“I think we would have a severely underserved population,” said Heather St. Clair of Nash and Edgecombe counties.

For many four-year-olds, N.C. Pre-K is their first experience with learning in a group setting. Children who don’t have experience in classroom settings simply know less about how to function in one. According to many contractors, kindergarten teachers report stark differences between a student who has experienced some formal child care setting — whether that’s in a home alongside other children, in a child care center, or in a public school — and a student who hasn’t.

“If we didn’t have pre-k, if we couldn’t get them in these programs, kindergarten wouldn’t be kindergarten,” said Bobbi Holly, the contact person for the Bertie County N.C. Pre-K contractor. “You would be spending so much of your time just teaching them the basics.”

This is specifically due to the importance of social and emotional development during the first 2,000 days of life. Children who have already had some practice interacting with new people, forming connections with caring adults outside of their home, being separated from their parents or guardians, and regulating their emotions in new environments are much more successful in transitioning to kindergarten, and beyond.

The main reason contractors were so distraught when imagining a future for N.C. Pre-K without having classrooms in public schools is that the early childhood education system at large simply does not have the capacity to fill the gaps that would be left.

And in at least six counties, school districts are the sole provider of N.C. Pre-K.

To qualify for hosting N.C. Pre-K, providers must have a four- or five-star license. Many parts of the state do not have enough of these licensed providers.

“All of the childcare in Polk County is only with Polk County preschools,” Amy Scott said. “There is none. No private, no nothing.”

Simply stated, the existing early childhood education landscape in North Carolina cannot afford to lose the classrooms hosted by our public schools.

Extending the benefits of public education

Public education can serve as a great equalizer, a way to disrupt the cycle of intergenerational poverty for at-risk children, families, and communities.

But the period of time in a student’s life when education is most likely to have an equalizing effect is the first 2,000 days.

Thanks to the work of parents, teachers, and other experts in the field of child development during the 20th century, North Carolina extended the benefits of public education to young children by providing universal access to kindergarten.

In the 21st century, we’ve begun the process of extending those benefits even closer to that moment when a baby enters the world.

Our public schools play an absolutely crucial role in supporting our youngest learners, and losing their participation would have devastating consequences for us all.

Behind the Story

In the second half of July 2023, I called all 91 NC Pre-K contractors statewide with a set of five specific questions. I spent 496 minutes on the phone interviewing 29 contractors and followed up with the rest by email, receiving an additional 21 responses. By late August, that put me at a response rate of 55%, covering 59% of our counties.