Share this story

- "Are those communities that have less access to teachers with bachelor's degrees, for example, are they being penalized when they probably are those who need the most resources?"

- A @trustfrlearning guide includes questions for educators to consider when measuring success at the classroom or program level and for policymakers when doing so at the systematic level.

|

|

Recent discussions on pre-K quality center around questions of what we should prioritize in early childhood classrooms — and how we should measure success.

A new guide provides a chance “to explore how to measure what matters most in early childhood settings and to think more deeply about how we measure equitably,” said Chrisanne Gayl, chief strategy and policy officer of Trust for Learning, a national organization that aims to increase access to holistic early learning environments like Montessori. “As we know, children develop in the context of millions of interactions with their environments, caregivers, and communities.”

The guide includes questions for educators to consider when measuring success at the classroom or program level and for policymakers when doing so at the systematic level.

It’s based on the fundamental idea that equity is not a separate measure from quality but an essential part of it — a quality program prioritizes equity of access, experience, and opportunity, the report says.

How is quality measured in NC?

In North Carolina, licensed early care and education programs are measured through its Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS), which awards up to five stars to programs. The state has one of the oldest quality rating systems, established in 1999, and in 2017 was spending more than any other state on its rating system— an annual $13 million, according to a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Stars are awarded based on environmental factors, like safety and the quality of materials, and teachers’ education levels. The same study found that programs were incentivized to improve certain environmental factors through the ratings and that parents were choosing programs with higher ratings.

The stars dictate how much money programs receive per child through the state’s subsidy program, as well as if the programs can host NC Pre-K, the state’s pre-K program for 4-year-olds. Programs must maintain four or five stars to host NC Pre-K classrooms.

Along with being rated through QRIS, NC Pre-K programs have their own requirements and standards, based on five developmental domains, according to the Division of Child Development and Early Education.

Equity in measurement strategies

No one tool can do everything. The guide from Trust in Learning provides 29 tools already out there for educators and policymakers to make their own decisions on which are most appropriate in reaching their vision of quality.

The guide categorizes these 29 tools into nine principles of ideal learning:

- Decision-making reflects a commitment to equity.

- Children construct knowledge from diverse experiences to make meaning of the world.

- Play is an essential element of young children’s learning.

- Instruction is personalized to acknowledge each child’s development and abilities.

- The teacher is a guide, nurturing presence, and co-constructor of knowledge.

- Young children and adults learn through relationships.

- The environment is intentionally designed to facilitate children’s exploration, independence, and interaction.

- The time of childhood is valued.

- Continuous learning environments support adult development.

Equity should be considered in the suite of tools chosen: in what is measured, how information is collected, and how the data are used after being collected, said early childhood measurement experts on a webinar reflecting on the report Thursday.

When deciding what is measured, it’s important to listen to the voices of people most affected by early learning programs, like parents, panelists said. What they care about might not be part of existing quality measurements but affects children’s access and learning experiences, like cultural and linguistic relevance.

When it comes to how information is collected, it’s important to have a diverse pool of observers that reflects the diversity of children and educators in the setting being observed, said Bridget Hamre, co-founder and chief executive officer of Teachstone, which owns CLASS, an assessment system focused on the quality of classroom interactions.

“What we know is our observer pool for CLASS is too white, you know. The typical observer is a 50-year-old white woman,” Hamre said. “Even with lots of training and experience, how well are they able to go into a very diverse setting and make a set of ratings that are … as unbiased as possible?”

Equity should also inform how the information is used. For example, if teachers’ levels of education is part of quality measurements, as is the case in North Carolina, a community should not be penalized for having less access to those staff members, said Jennifer Brooks, a consultant to Trust for Learning.

“Are those communities that have less access to teachers with bachelor’s degrees, for example, are they being penalized when they probably are those who need the most resources?”

If information is intended to help educators make decisions, tools should help teachers make sense of it.

“People get stuck,” Brooks said. “They have the data but they don’t know what to do with it. So it’s really critical for measurement tools to be providing information that’s translated into actionable steps.”

Quality on different levels

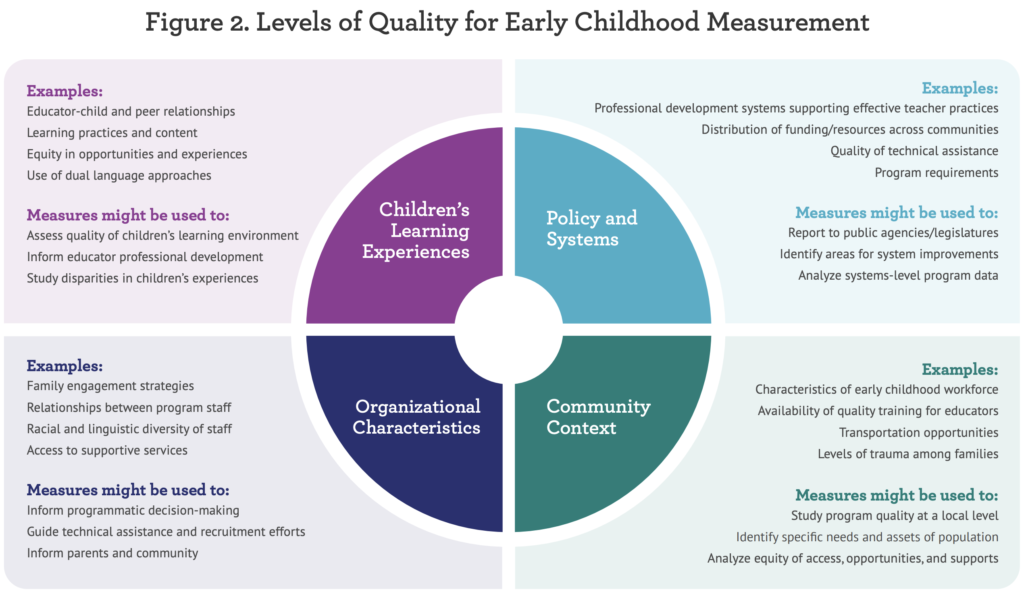

We often focus on children’s classroom experiences when talking about quality: what does instruction focus on? What do interactions between children and teachers look like?

But this is only one part of the picture, Brooks said. In the figure below, see how the report recommends a more holistic approach that considers factors affecting children’s learning:

- Organizational characteristics like the culture of a program, the diversity of staff members, and how the program engages with parents and others.

- Policy and systems structures like professional development and technical assistance opportunities, how funds are distributed across communities, and federal and state rules and regulations.

- Community context, like the early childhood workforce pipeline, the rural or urban nature of the community, and the levels of trauma among children and families.

Most of the 29 tools included focus on classroom interactions, highlighting the need for the development of tools that link these layers together, Brooks said.

The guide can help those closest to children — educators and program leaders — consider their own goals while still meeting state standards, said Lydia Carlis, chief program and people officer at Acelero and Shine Early Learning. Some of those qualities might overlap, and some might not.

“If we want to maximize its use, then we would focus really heavily on how you can do both,” Carlis said. “Some (aspects of QRIS) will be useful for informing environments and so on, and some will just be, ‘We can’t really figure out why it’s there, but we know we have to do it.'”

Carlis said working with parents, educators, and other stakeholders to answer these two questions is a great first step: “What would be different, better, enhanced for children, families, communities, if we achieved what we think is quality in our programs? … How far away from our ideal learning are we, and what are some steps that can take us to get there?”