|

|

The Great Recession hit all communities hard. Ashe County, known for its pumpkins, cattle, and Christmas trees, did not escape the economic downturn. In one of the county’s most populated places, West Jefferson, downtown buildings and storefronts sat unoccupied. Like so many Main Streets across the country, things were not looking their best.

But then, Jane Lonon, the now-retired executive director of the Ashe County Arts Council, started a program aptly titled the Empty Windows Project.

Lonon contacted building owners in downtown West Jefferson and asked if they would allow the Arts Council to decorate their empty storefront windows with local art. Kathleen George and Kitty Honeycutt of the Ashe County Chamber of Commerce say the initiative was incredibly effective.

“It gave the illusion of ‘Hey, we’re open for business, and we’re here!’ And really then the properties became much-coveted. You know, they wanted to be in that space. So it really helped turn around the vacancies in the buildings and so forth, and now this is a mecca. People come here just for the arts.”

Kitty Honeycutt, Executive Director of the Ashe County Chamber of Commerce

What more has emerged from Ashe County’s embrace of the arts? The development of future artists and musicians, strong partnerships, and economic progress.

Ashe County and its history of visual art

Thirty years ago, this rural community depended heavily on agriculture and manufacturing jobs said Rebecca Williams, program director at the Ashe County Arts Council. And while an industry of agriculture remains — Ashe County is the largest producer of Christmas trees in the country — the arts have become foundational to the local economy.

In 1996, the first of 17 murals was painted in West Jefferson. These pieces of outdoor art tell stories of the Appalachian region. While the majority of murals in the county are found in West Jefferson, they are spreading to other areas. A new one is set to go up in Lansing as well as in the New River State Park.

The New River State Park addition is the first in a series from the Mural Connectivity Project, developed to continue tourism growth and other economic development opportunities in the region. Honeycutt says the idea of this new mural is to help “cross-pollinate” the adventure tourist and the art tourist. Putting a mural at the New River State Park would allow campers and hikers to see how art is woven into the county. It would also allow art seekers to head into the park with their mural map and discover Ashe’s natural beauty. It is a win-win for the area.

Driving through the county, you could see any of around 150 barn quilts that adorn homes and farms. These pieces of art have become popular and the Ashe County Arts Council has made six different loop trails to help visitors tour these symbols of “comfort and family.”

A popular visit while in Ashe County is to St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in West Jefferson and Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Glendale Springs. These historic churches — St. Mary’s was constructed in 1905 and Holy Trinity in 1901 — house frescoes.

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church of West Jefferson. Caroline Parker/EducationNC

Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Glendale Springs. Caroline Parker/EducationNC

Frescoes are paintings done quickly in watercolor on wet plaster on a wall or ceiling, so that the colors sink into the plaster and become fixed as it dries. Frescoes were commonly used in ancient Rome, by the great masters of the Italian Renaissance, and by Ben Long in Ashe County in the 1970s and 1980s.

It is easy to see, literally, the importance of art in the community around Ashe County. Is that same feeling reflected in schools? Jill Gambill, visual art teacher at Ashe County Middle School said, “[The arts] is important enough to this county that they have funded an individual music and art teacher for every single school, and then more at the high school.”

Gambill’s position is only half-funded by the state; the county funds the rest. She is native to Ashe County and was a North Carolina Teaching Fellow who knew she wanted to return to the area. When students at her school sign up for electives, 95% of the students pick her class as their first choice. Why does she think that is?

“It is literally the only class where they can come up with their own right answer. Everybody else, you have to follow this prescribed thing, and art is the opposite of that.”

Jill Gambill, visual art teacher at Ashe County Middle School

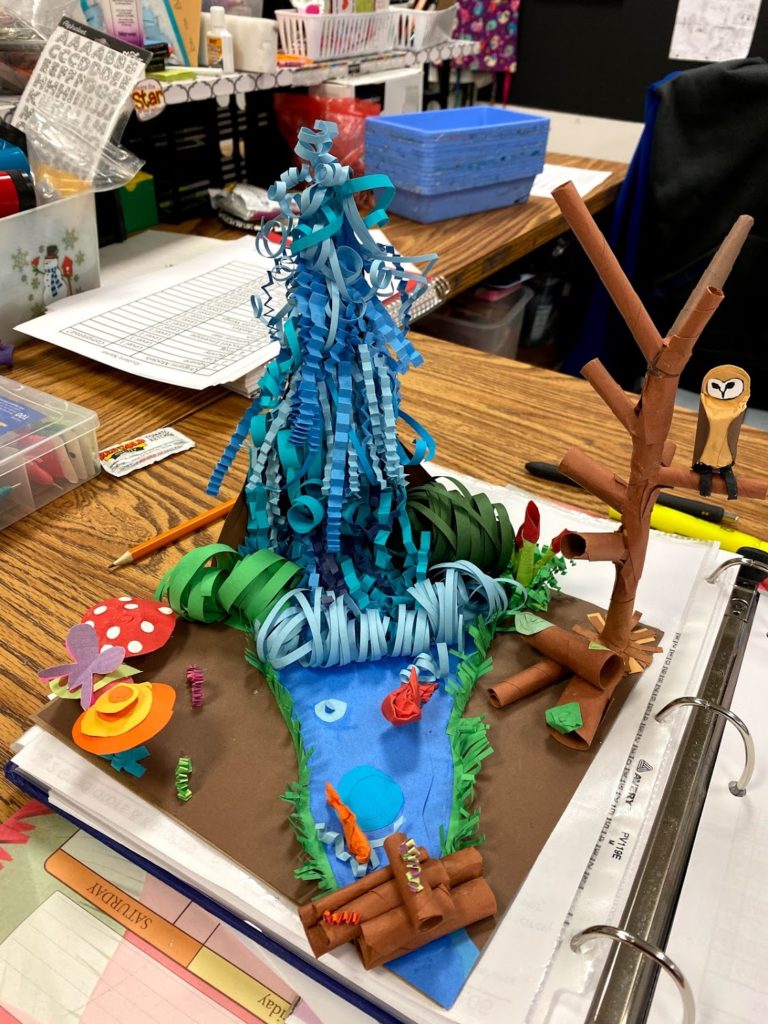

Paper project at Ashe County Middle School. Caroline Parker/EducationNC

Origami at Ashe County Middle School. Caroline Parker/EducationNC

Students in art class at Ashe County Middle School. Caroline Parker/EducationNC

JAMing with the Mountain Music class

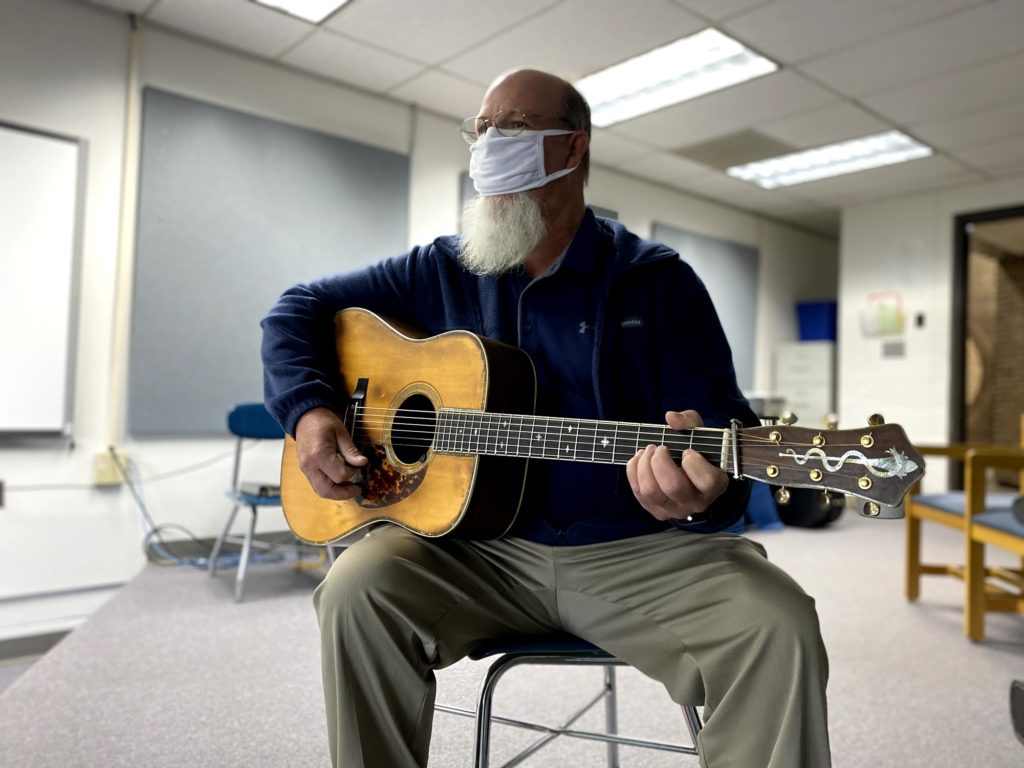

“This is not textbook music theory scales,” says Steve Lewis, instructor of the Mountain Music class at Ashe County High School, as he starts riffing the classic bluegrass tune “Nine Pound Hammer.” Lewis has worked in this position for 16 years at the school, picking and teaching students on the mountain the instrument of their choice. He has been playing all his life, and picked up his first guitar around the age of three. He has performed around the country and won first-place titles picking in both guitar and banjo. When describing the difference between classical music and this type of music, he said:

“They play the same piece verbatim exactly the way it was played 200 years ago. You can’t deviate or vary. What we do is, I tell you a story, and you tell someone else the story. It may change with the way someone else tells it, but the gist and the idea of the story should still be there.”

Steve Lewis, Mountain Music instructor at Ashe County High School

Lewis estimates he has taught around 300 students at the school, and countless others through private lessons. Appalachian music here is taught in the “knee-to-knee” tradition, according to Williams of the Ashe County Arts Council, and students learn so much from watching Lewis hold his instrument and seeing his fingers slide and pick.

The Mountain Music class grew from another local program called the Junior Appalachian Musicians — also referred to as JAM — which originated in neighboring Alleghany County and was adopted in Ashe 19 years ago as an after-school program for students interested in picking up a traditional mountain instrument. JAM programs are now all across the Blue Ridge mountains and the North Carolina Arts Council picked up the model years ago to create Traditional Arts Programs for Students, also called TAPS.

The JAM program has instructors that used to be students and it encourages older students to mentor those who have just joined. JAM happens a couple of days a week at the Ashe County Arts Council, which is housed in an old Works Progress Administration (WPA) building in downtown West Jefferson. Youth gather to play music and are surrounded by the building’s ever-changing art gallery. (When we visited, the Young at Art exhibit was on display, featuring student artwork from around the county.)

Students in JAM go on to play paying gigs in town and across the region. Listening in on their session, it’s difficult to miss the banter that happens in between picking. This space and program are an example of what sociologist Ray Oldenburg calls a “third place.” While “first place” is the home, and “second place” is work, a “third place” contributes to local life in a different way (like a coffee shop or a pub) and can be instrumental in building community, relationships, and local spirit.

“The Arts Council is very committed and passionate about providing art activities for students in our rural county,” Williams said. As we listen to students play, pick, and bow with the JAM program, their classmates artwork surrounding them, Williams statement seems apparent.