For all the positive research and outcomes that early colleges throughout the state have seen in the last decade, challenges remain. Take one small, new early college on the coast — Marine Science & Technology Early College High School (MaST) — which has survived Hurricane Florence, the death of a student, funding cut threats, community misunderstanding, and a brief closure all in its first year-and-a-half.

Principal Deanne Rosen said MaST is “finally in a good groove” after the Carteret County board of education closed the school last summer. Part of the board’s reason was that the state legislature threatened to cut its supplemental funding for Cooperative Innovative High Schools (CIHS) — early colleges and other schools that connect the high school experience with a head start on college.

Another reason for the closure, Rosen said, was a lack of clarity about what the school was all about.

“That’s one of the community disconnects,” Rosen said. “They see early college and they think we have the top of the top, and that is not the case. We’re very diverse here when it comes to academic diversity.”

Rosen and Kathy Bernstein, MaST’s counselor, wear many hats at the school and have made its staff and students their family. They said they are, in many ways, trying to rebrand the school, starting with moving from the term “early college” to “Cooperative Innovative High School.” They want to give the community a better idea of the range of students it recruits and the pathways the students choose.

“When you hear ‘early college’ like that, your mindset is, ‘Oh, they’re only looking for those two-year people who are going to transfer to other colleges,” Bernstein said. “I think (CIHS) really showcases who we are — more than just an early college.”

Ridge Hayden, a sophomore at MaST, is one of several students in his class who have become interested in welding through a program at Carteret Community College, the campus on which the high school sits and where students can start earning credits as early as their first year. Hayden plans to earn his welding certificate, his associate degree in diesel and heavy mechanics, and work directly after graduation. Rosen said the popularity of courses such as welding and aquaculture exploded this year, especially among students in their second year.

As students have been exposed to different courses and options, many like Hayden are looking to enter the workforce after high school instead of transferring to a four-year university. Rosen said the split is about one-third learning a trade, one-third earning an associate degree, and one-third transferring to a four-year institution. That last third, she said, is dwindling.

“They are really understanding the economic impact and job demands in our local area, and we’re seeing some of those that thought they wanted to go to a four-year university decide, ‘Hey, I can stay here and there are jobs that are in high demand, that are high-wage and highly skilled positions, where I can go straight into the workforce.'”

Rosen, a Carteret County native, said the connections and relationships students make now will help the county as they contribute to it. Community college opportunities such as welding (and underwater welding), hospitality management, marine sciences, and aquaculture are distinctive to the coastal community.

“It is all about networking and growing our local economy, which is the premise of a community college anyway,” she said. “When they started, it wasn’t so that we can get you to a four-year degree, it’s so that you can get back and grow our local economy.”

When Adrianna Seder heard about the school’s closure, she said, she was out of the country on vacation. “I was heartbroken,” Seder said. “I couldn’t believe it. Then I had to try to adapt to the fact that I was going to have to change schools.”

Seder said her first year at MaST gave her classes connections to her career. She wants to be an interior designer and plans to take entrepreneurship, engineering, and architecture college courses over her next three years.

“This is a good way to start thinking about my future and what I have planned,” Seder said.

Seder said she has found a strong sense of family, an empowerment in her learning, and individualized attention for career planning.

“Our first year here, it was awesome,” she said. “We all really got to know each other, and going through something like that together, in a way it brought us all together because we had to stick together in order to show people what this school is made of and how strong of a community it’s creating.”

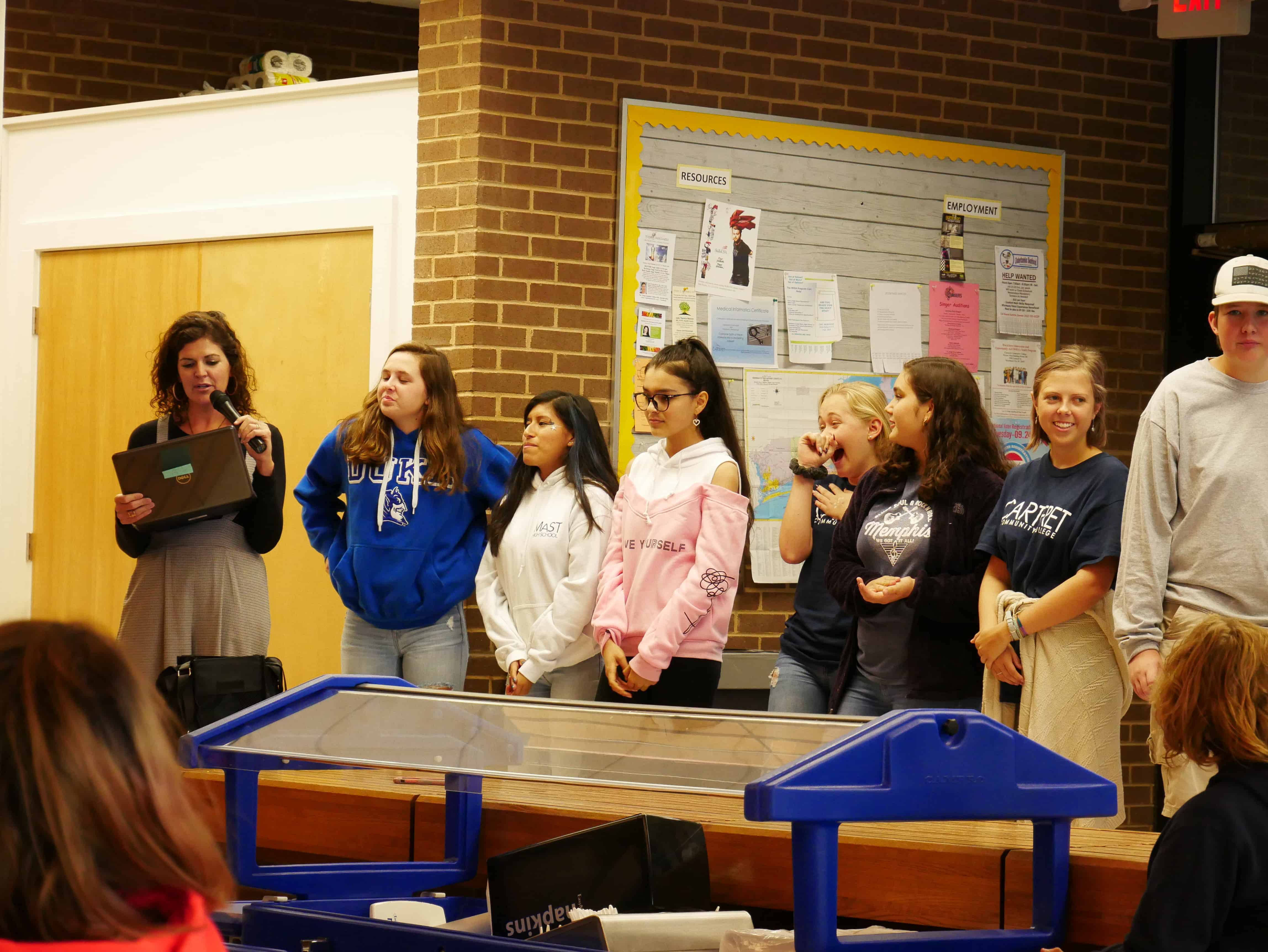

Throughout the six weeks of summer when the school’s future was unclear, Rosen and Bernstein were shifted to positions at other schools while they did everything in their power to save MaST. Students — both sophomores and students who had just been accepted as first-year students — and their families rallied around the school. Rosen said they attended the county board of education’s and commissioner’s meetings and spoke of the distinctive opportunity the school offered them.

“Our students and parents fought the battle to stay open because they believe in this program,” Bernstein said. “And to see 14- and 15-year-olds stand up at the BOE meetings and speak about their experiences here … it was impressive to watch.”

Students and staff got the word at the end of July that they’d reopen in the fall — nine days before the start of classes.

“It definitely takes a lot reflection and a lot of movement,” Rosen said. “We have this small building here … and trying to find space from July 29 to August 7, you prioritize. We look back and we made lots of lists, and it’s always putting the students first. And that’s why we continue to do what we do with this model, because it is such a good fit for these students.”

Bernstein and Rosen are first-generation college students, which is one of the target populations of the school. Statewide, CIHS programs are required to target at least one of three student populations, the other two being students at-risk of dropping out and students in need of an accelerated environment. Rosen said the school has students from each of those categories.

“You look at the entire child,” Rosen said. “You look at their background, where they’re from, what they’re leaving when they get on the bus in the morning, everything that they are doing because they’re trying to break the cycle of their family. And we’re here to help guide that. … We know the struggles, we know they’re having to work and come to school at an early age. We know that they’re having to leave here and go home and take care of younger siblings while their parents work. But we also are here to help them and be a part of their family.”

Every day, Rosen and Bernstein get one-on-one time with almost every student. With so much change, and with students losing one of their own peers to a sudden medical issue this past year, they said ensuring the mental health of their students is a top priority.

“Every day we talk to every kid,” Rosen said. “We know when they’re having a bad day, we can pull them in. … We talk to them together quite a bit just to help coach them and guide them. They go on about their day. It’s like we can get it before it escalates. We know these kids, inside and out.”

Recommended reading