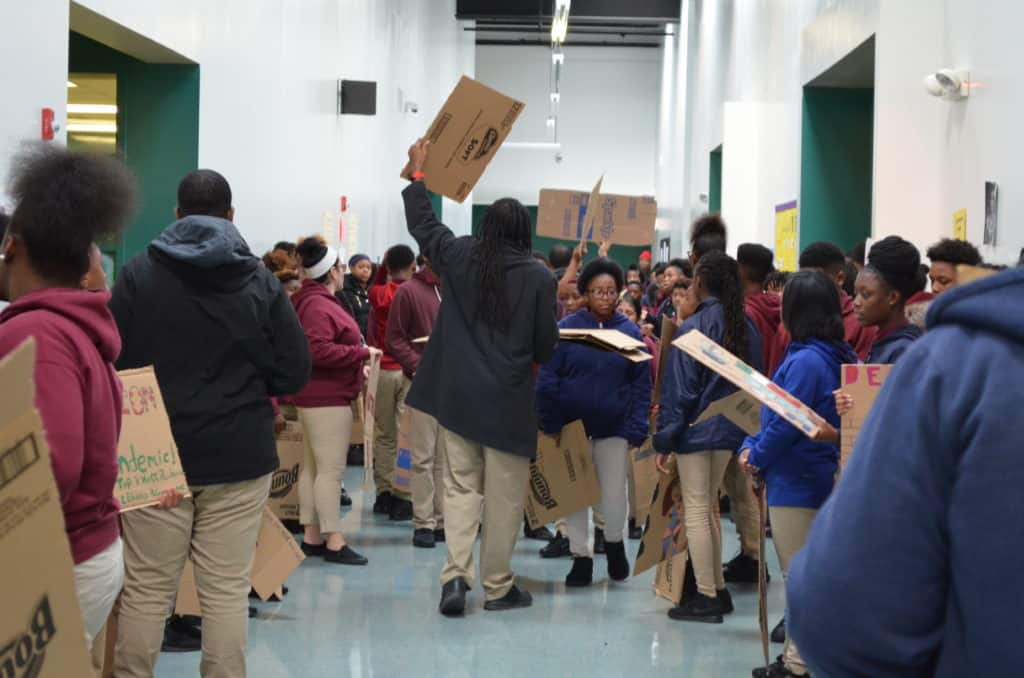

One Friday morning at Sugar Creek Charter School in Charlotte, a line of seventh graders filed out of the building and marched down the parking lot. They carried signs: “Women’s rights are human rights.” “Arms are 4 hugs.” “Free to speak.” “No more guns.” “Books not bullets.” And many, many more.

A police car escorted the students up to the sidewalk bordering a busy street. The students lined up and held their signs aloft, chanting “No justice, no peace,” under the direction of seventh grade social studies teacher Phil Javies.

The human rights march was the culmination of a long-term project that helped the students learn about civil rights, human rights, and the history of Americans speaking out about injustices.

At Sugar Creek, this is how school is taught — through projects. The next assignment for Javies’ class is a series of craft boxes that will help the students learn about the country by picking a state and illustrating information about it on what looks like a miniature float.

Talking about that project, and marching outside at the tail-end of the last project, the kids are enthused, the teachers are enthused, and everybody is having a great time. And learning.

Javies says for him it’s all about expectations. The ones he wants his students to have for him, and the ones he holds them to.

“I feel like if the expectation is met on both sides … we’re both holding each other accountable, we both care about what we’re here for, the outcome is tremendous,” he said.

Phil Javies’ advice for teachers:

Know your curriculum

“Whatever your standards are, know those. How am I going to be effective with these standards? I feel like every single time before I teach a lesson, I’ve practiced it a couple of times. Because those fumble moments are where you lose the kids. So I would say know your craft. Master your craft.”

Be consistent

“Being the same person that you are on the first day of school as you are on the hundredth day of school as you are on the last day of school. Because the kids are always watching.”

Have fun

“Yes, I get it that it’s a job. But it’s also a career that we chose. And so, if this is a career that you chose, I refuse to go anywhere every single day that is going to make you upset. I refuse. Even though education doesn’t get paid very much, it is one of the most valuable and important careers in the world. Because you nurture reporters. You nurture doctors and astronauts and other teachers.”

Focus on collaboration

“Collaborating with your teachers. Collaborating with the parents. Collaborating with athletics if they’re in a sport, so that everybody is on one page knowing what the teacher requires and so kids don’t fall behind. I feel like if we’re doing that kind of collaboration, there’ll be no child falling behind.”

A troubled kid takes the education path

Javies remembers being interested in education from a young age. Growing up in Boston, Massachusetts, when other kids would play house, he would play school. Though he didn’t imagine being a teacher; he imagined being the principal.

“They got to come in and control stuff,” he said. “So that was always me.”

In high school, there was an elective called Future Teachers of America. On a Friday, at the end of the day, Javies had free time to go learn about his interest in teaching, though he wasn’t always following directions.

“Sometimes I was going to the movies and going downtown to the arcade,” he said. “But there were times when I was going to the elementary school.”

He would shadow the teacher and help grade papers. He loved it. But he wasn’t always the kind of student who you’d imagine growing up to be a teacher. He called himself a “bad kid.” He would talk back to teachers and got suspended.

“That kid that you would be like, ‘That kid is the worst I’ve ever had?’ Phil Javies. It was me,” he said.

But, he added, there is a bright spot to having that kind of history.

“I think that also helped me being the educator, because I can pick out those kids,” he said.

Javies attributes his bad behavior as a kid to how he felt about his world. His home life wasn’t the best, and there were times that he was actually taken out of his home and put into foster care. He didn’t know who to turn to in order to unpack those feelings.

“I was upset. I didn’t have a place where I felt the teachers cared enough about me or respected me enough or I respected them enough to tell them my deepest, darkest secrets,” he said.

His trouble at school lasted until seventh grade. And it was a teacher that helped him turn around his behavior.

It was eighth grade skip day, and most of Javies friends were in the eighth grade. He figured he would go out with them, even though he was a year behind. He was having a good time and enjoying the day off at the school, but he took things a little too far.

He went to pick up a mop bucket, but it was filled with water and heavier than he thought. He spilled it everywhere. That’s when a teacher came out and started yelling at him. The teacher was an African-American man — the first African-American teacher Javies had ever interacted with.

The teacher expected more of Javies than his behavior suggested. He told Javies that he could see greater things in store for him and that Javies was better than his actions. That he was capable of success.

“The stuff that he said to me in that moment meant so much to me after,” Javies said. “I started realizing that I was better than my situation. That other people see this greatness in me. You see that I’m going to be great and I’m going to do stuff and I’m going to change the world and that I’m important. What? I’ve never been told that.”

The winding road to Sugar Creek

Javies didn’t picture himself as the kind of kid who could go to college. So he enlisted in the Navy instead. But his career there was cut short when he got injured.

After that, he decided to give a college a go. He began looking around and learned about historically black colleges and universities for the first time. He visited Winston-Salem State University and fell in love. He ended up attending there, double-majoring in elementary education and sociology with a concentration on social work.

“Going there, you had black excellence everywhere,” he said.

He said he learned a lot about expectations there. If he didn’t show up for class, his teacher would call him to ask where he was. People expected him to succeed, and that changed the way he thought about his expectations for himself.

“I was understanding that people are counting on me,” he said. “And I’ve always been a man who is big on my word.”

After college, he worked as a counselor at a nonprofit in Boston that houses urban students and buses them to suburban schools. He also went to graduate school.

But gradually he grew tired of life in Boston. Javies is a sharp dresser and wears suits all the time. He likes to look good, and that became a frustrating focus for some of his colleagues in Boston.

“I got tired of having meetings as a counselor about my personal [life]. A lot of the teachers there would be like, ‘Is that your hair?’ ‘How many suits do you have?'” he said. “We’re here because you’re trying to kick this child out,” Javies would say. “So, I’m like, I need us to focus on what we’re here for.”

He ended up leaving Boston to become an admissions counselor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. One day, he was hanging out with some friends at a bachelor party when he met a teacher from Sugar Creek Charter. He heard all about the school and what it’s trying to do.

The school is high-poverty and has a large concentration of black students. When Javies went to check the school out, he saw more black male teachers than he had ever seen in a school, which he liked. But it was the project-based learning strategy that sold him.

He said he was never a kid who was good at working in a box. He could get abstract concepts like math, but if you found a way to apply the math to a real-world situation, that’s when things would really click for him.

So he joined the school, where he has now been for seven years.

Expecting the most from students

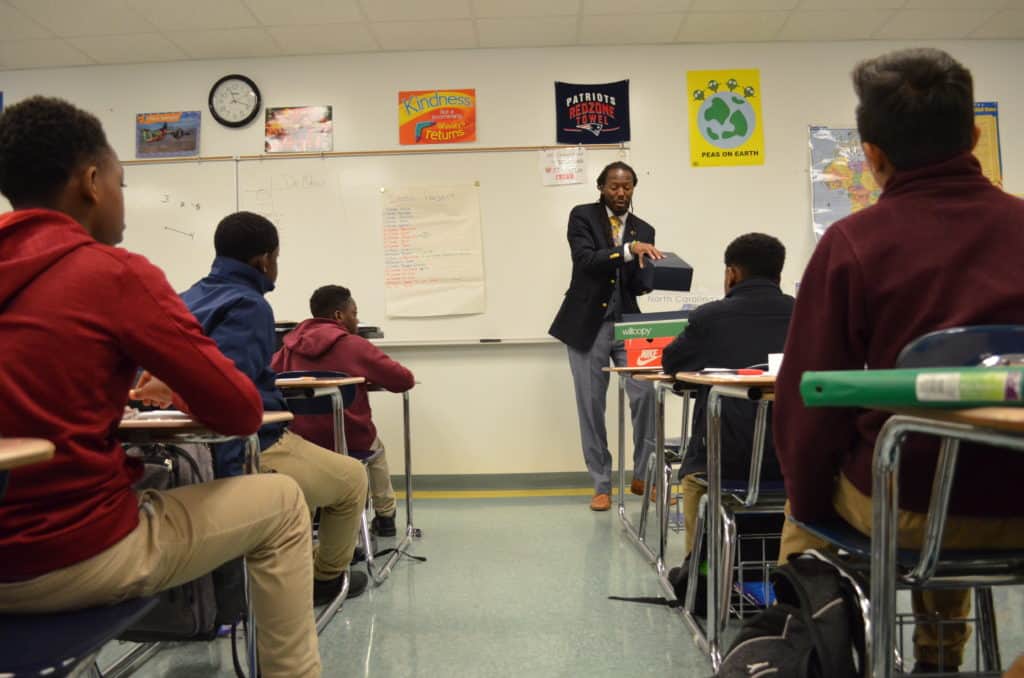

Javies said the key to his success with students is consistency and always letting the students know what to expect.

And it’s evident in the way he teaches. As he goes through the rubric for an upcoming project, he spends a lot of time laying out for students what is expected of them. He shows them what the project would look like if it didn’t meet his expectations. He has them explain why the sample project falls short. He also shows them an example of a project that fully meets the requirements. The students know exactly what they need to do to succeed.

But Javies’ class isn’t all serious business. He spends a lot of time joking and relating to students. But when it’s time to lay down his expectations, he can quickly switch to a serious demeanor.

“Let’s joke. Let’s have fun,” he said of his class. “But let us always be about our business.”

In addition to that eighth grade African-American teacher who taught Javies that he was capable of more, and his college experience that instilled a sense of excellence, Javies also attributes his focus on expectations to his grandmother.

She was from Barbados, and she always told Javies what he needed to do to meet expectations. She was fond of saying things like: “A man is nothing if he’s not of his word.”

Meanwhile, Javies had the chance to put that into practice when he was living with his mom.

“I was the person who was taking care of my brothers and sisters because my mom wasn’t there,” he said.

Javies said his notion of success for himself focuses around the kids and his job. He wants to know that the kids learned something. In fact, as the class lines up to leave the classroom, he will ask them if they learned something today. He does that at the end of every class. He said that when a tour is in the building and it stops by his classroom, or other teachers come to him to ask questions, those are other ways he knows he is doing a good job.

“I just feel like I want to be remembered as a great,” he said. “I probably will never be a Napoleon and take over the world … but when you think about education, will you think about Mr. Javies? And if the answer is yes, then I did what I was sent here to do.”