This story starts long before my visit to Hoke County on May 12-13, 2015.

This story starts when the superintendent, Dr. Freddie Williamson, was in sixth grade in our public schools in Sampson County. His teacher, Melissa Shaw, said,

“Stop! God gave you the same brain he gave everyone else.”

In that moment, Dr. Williamson realized he could do it. He knew he could and would succeed. And since that moment, poverty in the life of each and every student that has crossed his path has never been an excuse for anything.

Community opportunity is tied to student opportunity

Historically, across races, Hoke County has been poor by any definition. Nestled in the Sandhills between Fayetteville and Pinehurst, its identity is not defined by the military or by golf courses. Its location, which at one point in time may have been a liability, is now an asset, and the county has chosen to position itself as a “world-class learning center.”

I first visited the Hoke County Schools with the Z. Smith Reynolds Leadership Council in June 2013. Rural areas were still reeling from the recession, and the House of Raeford had just announced that it would close its chicken slaughter plant – 1,000 jobs – and the cook plant – 400 jobs. The community was worried about jobs.

Those worries are gone. Since 2013, not one but two hospitals have opened in Raeford, and the district profile says, “Hoke County has evolved from a small, rural, economically distressed, tobacco-dependent county supported by sawmills, the textile industry, and tobacco farms, to one of the top five fastest growing counties in North Carolina.” Butterball bought the cook plant, restoring 367 jobs.

Parcel after parcel of farmland is available for commercial use. Jodie Bryant, the director of public relations for Hoke County Schools, says driving down Highway 401 you see business after business popping up. Indoor skydiving is even an option.

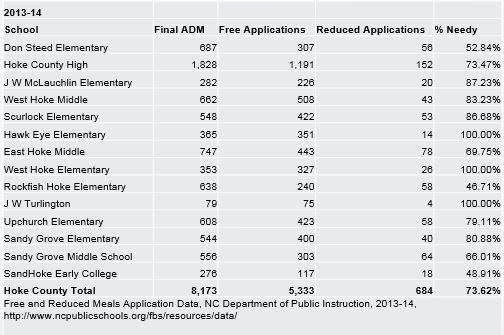

Even though the county is growing, many of the students still live in poverty. Teachers ride the bus home towards the end of the school year with students. “It’s literally like stepping back in time,” says one teacher. “It reminds us how isolated the students are.”

Every aspect of the school experience is designed to give these students a roadmap to success, says Bridget Hayes, principal of Hawkeye Elementary and the district’s principal of the year. Several things make that possible here.

The look and feel of diversity

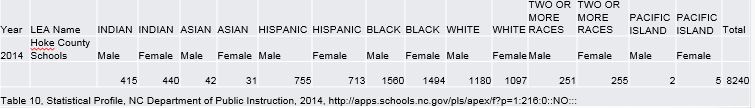

Race plays out differently here than in other communities in North Carolina. Diversity in Hoke County is multi-faceted. It’s black and white, but it’s also American Indian, migrant, from up North, and often associated with the military in some way or another. Poverty ripples through all of these communities, and with the exception of the American Indian community, most housing is integrated.

Dr. Williamson may have led the way, but there has been buy-in among all the stakeholders. Over and over and over again I am told, “We will not allow poverty to be an excuse,” and “education is the way out of poverty.” For all kids. Period.

Easier said than done.

Alignment of leaders

There is another thing that makes this possible here – alignment of the administration, the school board, and the county commissioners. Scale helps. There are just five school board members and five county commissioners.

Deb Dowless, the assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction pre-K to 5, knows not all school boards are like the one in Hoke County. At the board meetings, the administration and the board sit around the table together. Protocol and process rule, but there is conversation and give and take. Dowless says, “Our board is very supportive. They treat us as the experts. They trust us.”

Deb Dowless, the assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction pre-K to 5, knows not all school boards are like the one in Hoke County. At the board meetings, the administration and the board sit around the table together. Protocol and process rule, but there is conversation and give and take. Dowless says, “Our board is very supportive. They treat us as the experts. They trust us.”

At a school I visit, two county commissioners are there. James Leach is the chair of the county commissioners, and he has served for 20 years. Harry Southerland is a county commissioner and was on the school board for four years. Leach says, “if you educate a child, they will contribute back to the community.” Southerland says politics are not paramount in Hoke County. He says, “Our community comes first. Our students come first.” They all emphasize that this is a community committed to education. And they are in a school on a school day seeing and hearing the opportunities and challenges first hand.

School board attorney Nick Sojka knits his fingers together, emphasizing just how important it is that the work of the school board and the county commissioners is interconnected.

A colleague tells me off the record that while some of this alignment can be cultivated, and has been cultivated by Dr. Williamson, some of it is embedded in the history of the place. The local Kiwanis club has been integrated since the early 1970s. A legendary principal, Raz Autry, integrated the high school around the same time, and his approach made it clear to everyone in the county that each child having access to a high-quality education was the value, the only value. John D. McAllister, a prince of a man according to everyone I talked to, chaired the school board in the 1990s – all setting the stage for a community that would choose to value the education of each child into the 21st century.

Mary McLeod, the principal of West Hoke Middle says, “We show the child love. We show the child, we’ve got your back. It takes the whole community to raise these children.”

The principals are principled

During my visit, I met with many of the principals of Hoke County and the district leadership for five hours. Dr. Williamson was not in the room.

It was an unvarnished, raw conversation about what it takes to educate kids in poverty. The energy was palpable. The commitment unwavering.

“Every parent sends us the best child they have.”

“The students don’t know they are poor.”

“Everyone in the building needs a better understanding of the kids walking in the building.”

“We have no clue what is going on in these kids’ households.”

“Every teacher is going to have to be more than just a teacher.”

“Poverty is not an excuse. It is our motivator.”

“We love education. We eat, sleep, and dream education.”

Principal McLeod concluded, “These are children. They need love, respect, relationships. And in return, they show us the utmost respect. This gives them an inner strength.”

“Our relationship with our students makes us stand out in the state of North Carolina.”

No one is left out of the process. The principals know that the smile on the bus driver’s face is the first thing each student sees in the morning. The school experience starts there. Which brings me to the books.

Books, books, and more books

At some point during the five hours, they tell me that every student is expected to read 25 books over five years. But it is not just the students that are reading.

Each year, all employees, from the bus drivers to the superintendent, read a book together. It started with Ruby Payne and her book, “A framework for understanding poverty.” From her book, they learned that all children can learn no matter where they come from.

Another year, they read Eric Jensen’s “Teaching with poverty in mind.” In fact, when I visited with the ZSR Leadership Council back in 2013, they gave each of us a copy and asked us to read it. They wanted us to understand that poverty is nuanced – that situational poverty is different from generational poverty is different from absolute poverty is different from relative poverty is different from urban poverty is different from rural poverty. They wanted us to understand the four risk factors of poverty: emotional and social challenges, acute and chronic stressors, cognitive lags, and health and safety issues.1 They wanted us to understand that teaching these kids in a way that makes it likely they will escape poverty has to take all of this into account on the macro and micro level, day in and day out. There is nothing easy about this work.

They mention the other books that have played a role in defining collectively how they think about educating kids in poverty, including “Our iceberg is melting,” “On common ground,” “Readicide,” and “Results now,” which they have read twice.

Over time, the reading of these books has become so important that Principal McLeod says most schools have a book study for everyone in the building. They need buy-in from the bus drivers on up. They need everyone to believe that these kids can do it, and the actions of everyone needs to be aligned towards that goal. Each year, they are always thinking and talking in formal and informal venues about the book. Conversations happen at ballgames, and then somewhere along the way they describe osmosis kicking in. The upshot, the principals say of this book-oriented, ongoing conversation about work of teaching kids in poverty?

“Dr. Williamson is growing us as leaders.”

And over time the focus has shifted from the teachers and teaching to the learners and the learning.

How this is implemented in the classroom

An interesting thing has happened in Hoke County. While many school districts have implemented magnet programs, year-round schools, and other choices that allow different schools to offer fit to different students and families, the Hoke County Schools have moved to equalize the offerings at each school so they can sell every school as a great school. In fact, they want to make sure that every opportunity available to a student at their early college, SandHoke, is available to each student in the district. So, next year, with a cohort of 9th graders, they will pilot a program that allows students to pursue an associate’s degree in a traditional high school.

The idea is to connect everything, and I do mean everything, to a long-term vision for students of college and/or career. The messaging is inescapable.

Colleen Pegram, the principal at SandHoke Early College, says, “The struggle is real. We’ve got to meet them where they are and move them to the next level.”

They say five things are key. High expectations for the administration, for teachers, for parents, and for students. All students are provided with a rigorous curriculum. Students are empowered to be responsible for their own learning. They intentionally work to build relationships with parents. And early interventions are essential.

When it comes to that rigorous curriculum and what actually happens in the classroom, the district has chosen and implemented LDC and MDC, which I learn stands for Literacy Design Collaborative and Mathematics Design Collaborative.

Hoke County is the only district in North Carolina that has implemented LDC in grades K-12.

According to the Southern Regional Education Board:

Literacy Design Collaborative (LDC) and Mathematics Design Collaborative (MDC) help students reach the deep learning necessary to master college- and career-readiness standards.

These frameworks give teachers a way to build lessons that engage students to read, think about and write about challenging texts in all disciplines. In math, students learn the why as well as the how by developing their math reasoning and problem-solving skills. Students struggle productively and learn more; in essence, teaching is shifted so that students take ownership of their learning and perform at higher levels.

The LDC and MDC frameworks were designed as tools and strategies for classroom teachers to create and share effective assignments aligned to their curricula.

Implementing LDC systemwide as the instructional framework in Hoke County has increased student confidence and improved listening and speaking skills, leading to better debates, presentations, and other work product, says the leadership team. They expect to see an increase in achievement scores. LDC is “nonnegotiable.”

Shannon Register, the assistant superintendent of secondary education, says, “I am most proud of the opportunities we have opened up for our students.”

The school buildings are kept open late so students can work. Transportation home after hours is provided. Principal Pegram says everything is done to make sure “there are no excuses for not being successful.”

Dr. Williamson

This story begins and ends with Dr. Williamson.

He wasn’t in the room during our conversation. His name could have never come up. Some superintendents are not beloved. But from the books to LDC/MDC to the no excuses philosophy, it is clear that the Hoke County Way is inspired by Dr. Williamson.

Principal Kim Gray says, “He is a visionary. His legacy is the capacity he has built in this district. Hoke County Schools will continue to grow.”

It is also clear Dr. Williamson does not sleep. Nikki Buxton, a seventh grade math teacher, says, “Dr. Williamson brought my calculators and snacks to summer school.” She still can’t believe it. She was so impressed she told her mom.

The staff says, “To have a leader that believes in us helps us cultivate our passion.”

The Hoke County Way is not for everybody. Turnover is high – 25% – and of the teachers that left last year, half said it was because the district asks too much of them. It is a price they are willing to pay. Failing the students is not.

“Our journey is North. We are all about continuous improvement,” says Principal Gray.

Additional resources

Dr. Williamson is a big proponent of High Schools That Work (HSTW). A program of the Southern Regional Education Board, HSTW is the the largest school improvement initiative for high school leaders and teachers. Here is information about the summer conference in Atlanta from July 15-18, 2015, which they say is a must for professional development.

To learn more about LDC and how it works to change the classroom experience, here is the website, here is the LDC resources webpage including a module template, and so you can see how this works in practice, here is an LDC Elementary Argumentation Module Template on “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” for fifth graders. Here is some additional information about MDC.

The Hoke County series

Monday: No excuses

Tuesday: Problem solved

Wednesday: “Why not us, why not now”

Thursday: Developing readers, not test takers

Friday: Fostering academic potential, skills, and behaviors now and in the future