Everywhere I traveled on EdNC’s blitz of all 58 community colleges, transfers came up.

Transfers are about people, I learned.

At Rowan-Cabarrus Community College, they told me the story of Roa Saleh. Saleh graduated in 2016 with an associate in science, went on to complete her bachelor’s degree at UNC-Chapel Hill, then went to the Johns Hopkins to work as a certified medical laboratory scientist, and now lives in Charlotte and works at Atrium Health.

But Eva Nicholson, another student at Rowan-Cabarrus who was the student body president in 2018-19, told me the other side of the transfer story. Growing up in Youngstown, Ohio — a town made famous by Bruce Springsteen with his song about the decline of the steel industry — Nicholson said, “A four year university was invisible to me.”

Transfers are about pathways, I learned.

At Stanly Community College (SCC), Robin McCree, the executive vice president of administrative services, told me, “a student is a student is a student.”

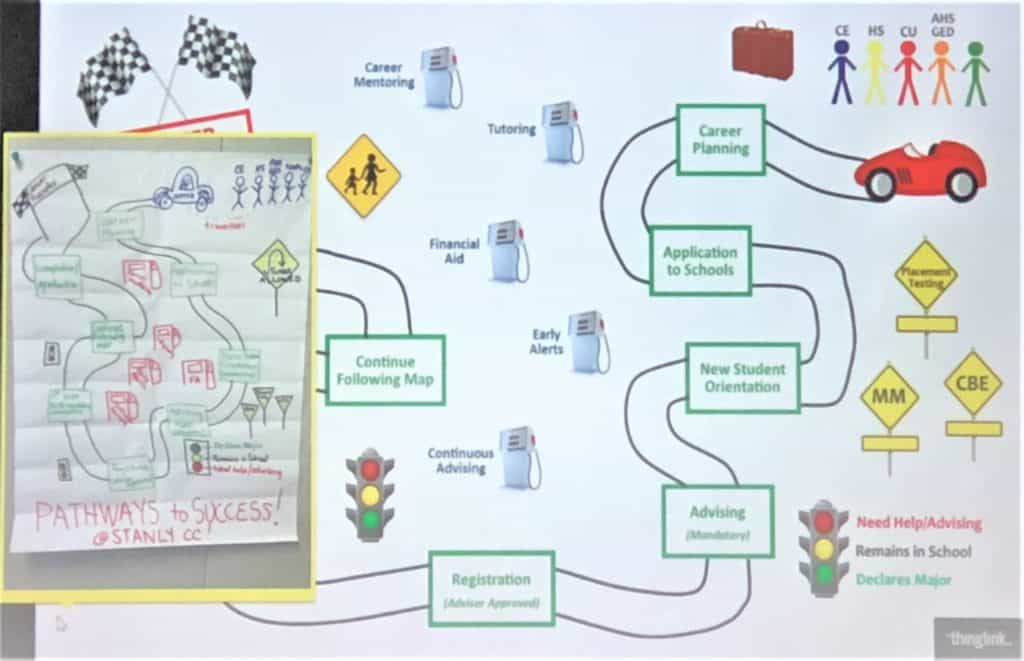

In 2015, SCC became one of 30 institutions of higher education across the United States — and the only one in North Carolina — selected to participate in the American Association of Community Colleges (AACC) Pathways Project (see the new pathways resources website). The three-year project is designed to build “capacity for community colleges to design and implement structured academic and career pathways at scale, for all of their students.”

You can see below some design thinking that emerged from the project about student pathways to success. Even more importantly, the college embraced the idea that “u-turns are allowed.”

To date, SCC has designed 35 pathways. Here is what each pathway looks like with information about earnings and projected job growth:

The goal is a seamless educational experience for all students, even if there are u-turns

I first learned about “student swirl” and the “seams in seamless” from Scott Ralls, long before our blitz. In August 2015, when EdNC was just eight months old and Ralls was president of the NC Community College System, he testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. He said,

First, we know students are more likely to find success when they continuously progress along coherent curriculum pathways.

Second, we know students are more likely to find success when they start with the end in mind and have outcome milestones along the way.

Third and relatedly, we know the success goal many of our students pursue is a skill and a job.

Fourth, we know that most of our student pathways to success run through our institutions, they don’t begin and end there, and students’ personal pathways aren’t typically confined to single institutions. We have to be willing to embrace the reality of “student swirl,” but be diligent in creating more coherent pathways across institutions and educational sectors, which is why tight, structured collaborations across educational partners are so important. Community colleges are uniquely positioned, in this regard, as what I like to

refer to as the “seam in seamless education.”

Finally, we know that what is important in the end is the number of successes we collectively help produce, not just the percentages within our individual institutions.

Ralls is now the president of Wake Technical Community College, and recently he introduced me to Michael Denning. Denning is an example of a student who found success by continuously progressing on a coherent pathway.

You can see in the following video that he earned two associate degrees, then a bachelor’s and master’s degree in three years at ECU, then a certificate at Stanford University (part of his master’s), before getting a second master’s at Columbia University, and now he is going back to ECU for medical school.

Students just need to see the options and experiences that are available to them, Denning says, adding, “If you can see it, you can believe it, and therefore you can achieve it.”

For other students, Ralls’ concept of student swirl is very real.

After Anna Burby graduated from high school, she was ready to get out of her hometown. She enrolled in a private college.

“I loved everything about it,” she said. But the last day of Christmas break after her first semester, worried about student debt, she headed to Central Carolina Community College and enrolled there instead.

Burby graduated in May 2013 with an associate in science and enrolled in a four-year university. But she didn’t actually start taking classes. Frustrated with the lack of information about the cost and unable to find someone to help her, she didn’t continue with her four-year degree in the fall.

Her advisor at Central Carolina helped Burby re-enroll. She earned an associate in arts and her credits eventually transferred to the College of Natural Resources, a smaller school within the larger university world of N.C. State. Burby graduated with a bachelor’s of arts in ecosystem assessment in 2015.

One advisor at Central Carolina kept Burby on her pathway. But how many students don’t get a degree because they don’t find that one advisor?

Time for another comprehensive study of our articulation agreement?

Let’s travel back in time. North Carolina’s first Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA) passed in 1997, and generally, policy analysts and researchers think it takes about five years to really integrate these agreements into policy and practice on the ground — unless you are in Singapore where they can just mandate it and will it to be so in about a year!

So in 2004, the North Carolina General Assembly commissioned a study of the CAA. Here it is for your consideration. It was back in the day of 188-page reports, but please take a look at least at the executive summary.

You can see the scope of the 2004 study on pp. ii-iii. Many of the findings and recommendations remain relevant today. And while it is good that continuous improvement is built into our articulation agreement process now, there is still too much we don’t know.

Perhaps most important, articulation agreements remain historical, policy, and planning documents that didn’t and still don’t meet the information needs of students. This report asked important questions: Should there be a single website for all transfer students? Do we need a transfer bill of rights for students? Should there be a coordinated marketing campaign on student pathways?

The articulation agreement study also points to particular pain points that still need to be researched: Are students getting appropriate credit for AP and early college courses? Should students who come back be allowed to start over on their GPA?

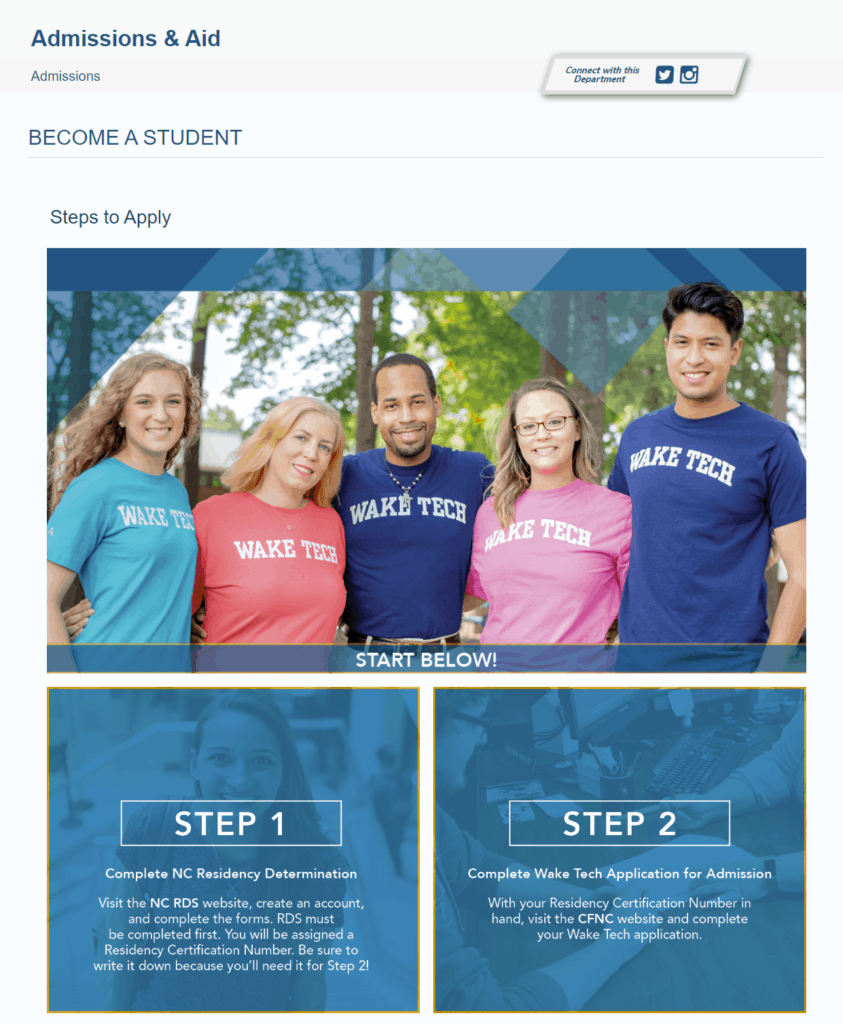

Even as EdNC.org conducted our research on transfers, it became clear what isn’t at all clear. Community colleges have open enrollment, but it feels like an admissions process to students complete with application and residency determination. Changing just the word apply to enroll would make a difference.

It is also not clear if students know about or are using the appeals process for transfer credits in Appendix E of the Comprehensive Articulation Agreement.

More recent research by The Belk Center points to other questions: Why exactly are more students transferring but fewer are earning degrees?

A comprehensive study like this also would provide an opportunity for our state to rethink its long-standing institution vs. student orientation. And it would also provide an opportunity to catalog all of our bright spots in transfers, like C-STEP and C3.

The NC Independent Colleges and Universities are another bright spot

Hope Williams, the president of NC Independent Colleges and Universities (NC ICU), knows her 36 institutions of higher education are the “only four-year institution in many parts of the state, especially in rural areas,” and she adds that “private colleges are affordable for thousands of North Carolina students with limited and even with no financial resources.”

When it comes to transfers, NC ICU coordinates discipline-specific articulation agreements with the UNC System, including RN to BSN; music, theater, fine arts; and soon offering teacher education in addition to psychology and sociology.

NC ICU also is involved in a pilot transfer pathways program designed “to determine best practices for two-year college-to-private college pathways that can be replicated in other states.” They are conducting peer-to-peer visits to improve procedures for recruiting students, fostering academic advising, and bringing faculty into the process.

And in December 2019, Williams announced $60,000 in grants to implement a reverse transfer program. “The Reverse Transfer program will enable more students to earn associate’s degrees, thus making progress toward the state’s education attainment goal,” she said. “The program also will increase graduation rates at two-year institutions and will provide incentives for the students to continue toward their bachelor’s degree.” Changes are also being made to the student information systems so course progress can be reported to the National Student Clearinghouse.

“Helping students with ‘some college, but no credential or degree’ come back to receive one will involve a lot of transfer students and letting them know about all the options available to them: in-person, on-line, mini-semesters, year-round cohorts, weekend programs, etc,” Williams wrote in an email. “We must be successful at reaching these transfers, and especially the thousands of adults with no credential or degree in order to be successful in reaching our myFutureNC goal.”

Ralls is right: Transfers should be about what’s best for students, not institutions

North Carolina has a lot of assets to leverage to attain the myFutureNC statewide attainment goals of 2 million North Carolinians with a high-quality credential or degree.

With 16 universities in the UNC System, 36 independent colleges and universities, and 58 community colleges, North Carolina doesn’t have a lot of educational deserts. Our community colleges have open door policies, and almost everyone in the state lives 30 miles or less from one.

In our series on transfers this week, you’ve read plenty of suggestions about how to improve transfer policies.

But some strategies in play nationally don’t get talked about in North Carolina, and it’s time to ask why. And if the answer is because of turf, then that’s not ok.

Recent research by the Education Commission of the States, for instance, finds that 23 states allow community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees. Take a look at the research.

The process of establishing the myFutureNC goal brought educational stakeholders together and prompted questions about what is in the best interests of the students, the workforce, the economy, the state, and our future.

Transfers are about people on pathways, and when our students make the inevitable u-turns, the question going forward should be: Are our transfer policies designed to support them? We know what keeps our students on the path to a degree: early alerts, continuous advising, assistance navigating financial aid, tutoring, and career mentoring, among many other interventions that change lives. This article on the love and respect transfer students need and deserve by Todd Rhinehart, the vice chancellor of enrollment at the University of Denver, is worth a read.

As Janet Spriggs, the president at Forsyth Technical Community College, told me once, “We chase students because we can change lives if we catch them.”

When our students make a u-turn, it’s on us to chase them.

“What is important in the end is the number of successes we collectively help produce.” — Scott Ralls

Editor’s note: Education Commission of the States just updated a 50-state comparison on transfer and articulation policies.

Recommended reading