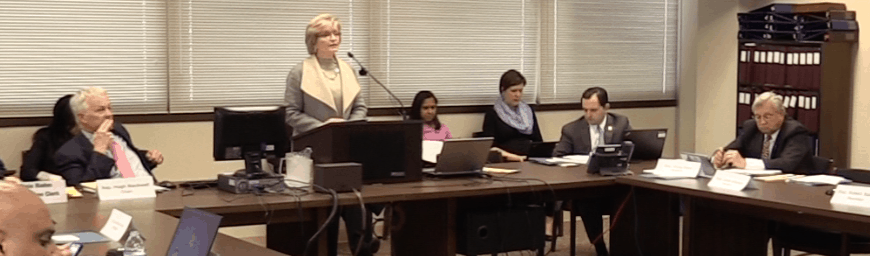

The setting had none of the trappings of a campaign rally – no red-white-and-blue bunting, no thumping amplified music, no supporters waving printed placards. A significant early moment in North Carolina’s election year took place last week in a nondescript legislative committee room, with lawmakers sitting at dark brown tables, some with their laptops open.

Standing behind a low podium before the House Select Committee on Education Strategies and Practices, Dr. June Atkinson, the state superintendent of public instruction, outlined a proposal for a 10 percent across-the-board salary increase as well as other elements of an enhanced pay system for public school teachers. Atkinson, a Democrat running for her fourth term, thus illustrated the agenda-setting capacity of an elected officeholder, a power of incumbency, especially in a campaign year.

Of course, teacher pay was destined to remain high on the state’s agenda this year, evident even before Atkinson spoke. During the 2015 legislative session, Democratic Rep. Graig Meyer speculated openly that Republican lawmakers would approve a minimal raise as a prelude to approving a larger raise in the middle of an election year. The operative question, then, is how would the pay-raise issue play out, both in terms of pay level and of political credit or blame.

It is fair to say that Atkinson is not an influential figure around the General Assembly with its veto-proof Republican majority. House Speaker Tim Moore sent a letter to The News and Observer, characterizing her proposal as not “practicable,’’ and declaring, “Elected officials should never play politics with people’s paychecks.” The Atkinson pay plan is unlikely to win approval from Republican legislators or the Republican in the governor’s office, Pat McCrory.

Still, her initiative has already had the effect of giving newspaper editorialists and advocacy commentators an issue to debate. What’s more, it has given Democrats a standard by which to measure what Republicans enact in the short session of 2016.

The Atkinson 10-percent proposal dominated the headlines. But her plan had additional significant elements. A “wedding cake approach,’’ she called it, with a salary increase for all teachers as the wide base layer, atop which would go pay for teacher-leaders, funds to recruit teachers to low-performing schools and bonuses to schools that showed academic advancement. She also gave lawmakers a little lesson in the difficulty of fashioning a merit or differentiated pay plan for teachers.

In a state confronting potentially debilitating shortages of high-quality teachers and declining enrollment in university schools of education, what Atkinson has done is to place a serious issue where it belongs: in the political process for voters to examine. To describe it as playing politics is, of course, playing politics, too.

And Atkinson is not the only statewide elected official who has found ways to influence the public agenda. Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Forest has made his presence felt on education issues from digital learning to charter schools to Common Core. He recently nudged the state Board of Education to order up a revised report on charter schools and released a video about charter schools. Forest raised his voice earlier than most in challenging the Common Core standards, a move that led to the legislature authorizing a study group to propose alternative state standards. He is holding roundtables with business leaders about education issues.

As a result of a trend that pre-dates both Forest and Atkinson, the public offices they hold have been considerably weakened over time, and the power to shape the state’s education agenda has fallen largely to the governor over the past generation.

Not so long ago, the lieutenant governor had the power to appoint Senate committees and to assign bills to committees, often with the purpose of getting certain measures approved or killed. The lieutenant governor serves on boards, councils, and commissions – including the State Board of Education. But now the Senate leader appoints committees and assigns bills, with lieutenant governors’ role in the Senate little more than pounding the gavel and calling on members during floor debate.

The current Republican legislative majority has imposed budget cuts on the Department of Public Instruction on top of earlier cuts to the bureaucracy supervised by the superintendent. Democratic Governors Jim Hunt and Mike Easley both succeeded in launching major initiatives by working around or going over the heads of Atkinson and her predecessors. Six years ago, Atkinson sued Governor Bev Perdue and the state board to preserve her authority within the state education department.

So, even with her office diminished in governmental power, Atkinson found an agenda-setting voice. And even though her speech won’t compete with presidential candidates’ rallies, the Democratic superintendent has elevated the political debate over how North Carolina should pay teachers to recruit and keep a high-quality corps in its public schools.