Two weeks ago, I gathered with 120 students in Raleigh for an all day public policy bootcamp. The students asked, and answered, insightful questions about our society.

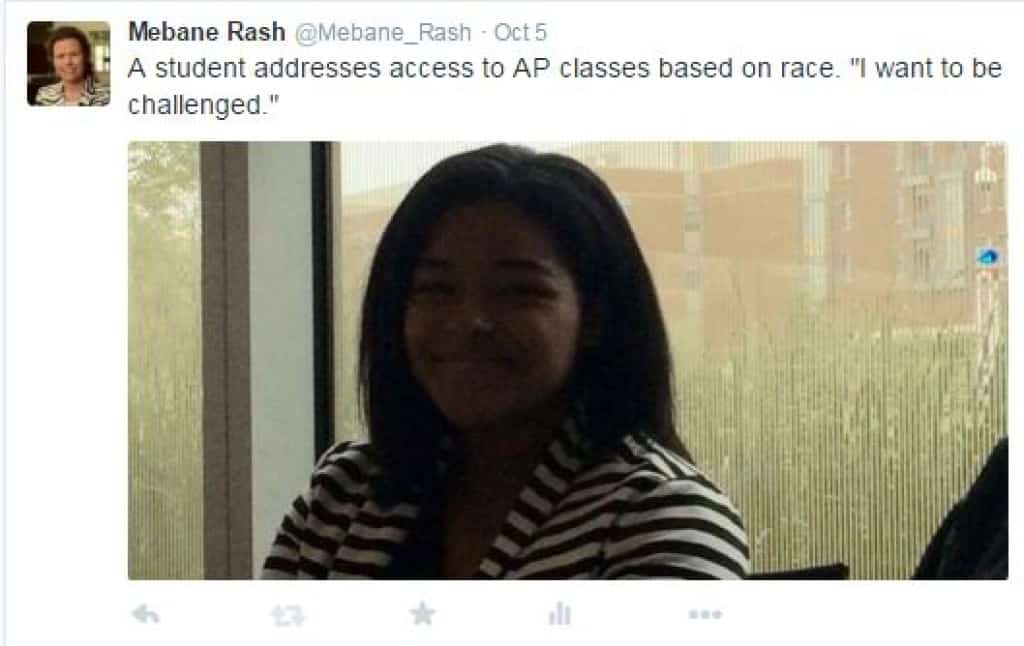

One student, sharing her own story, challenged what she saw as racial bias inherent in placement among challenging courses, which sparked a conversation as important as any I’ve heard about student placement. She received responses that challenged her views, but she did not back down.

It has been said that moral courage is one of the rarest commodities, and she showcased it in spades.

In breakout sessions in the afternoon, I was blessed to see real bravery in action as I led students through a storytelling exercise.

To tell your own story requires great bravery. To place your own memories out into the world, or your own viewpoint, or to offer a lesson that you have learned requires you to acknowledge that you will likely generate a response. Worst of all, it requires you to be brave in case no one actually responds.

It has been my privilege to watch Nation learn to share his story with students. Talk about bravery. The public policy boot camp reminded all of us that our students want to talk, they have important ideas to share, and it made us wonder:

Are we listening to our students?

The Associated Press reported on Monday, “The number of youth suicides in North Carolina increased by more than one-third between 2013 and 2014 and has doubled since the start of the decade, a child safety panel reported Monday in its annual review of child deaths in the state.” Are we listening?

Many teens are willing to talk, but kids often have a particular time of day when they are more likely to talk…and someone has to be there then to listen. For my oldest son, Hutch, he talks most freely on the way home from school, before bed, or in the middle of the night when his big questions about life weigh on him. As a younger child, Hutch called these “blue nights” because it was then, and only then, that he would talk to me until he was blue in the face.

As we encourage students to tell their story and talk to us about their school experience, trauma, and the change they want to see in the world, let’s commit to listen. — Mebane Rash, CEO, EdNC

It is story, married with fact, that helps explain our world.

In my life, and my career, I’ve learned from many great storytellers, including Jonathan Opp, the chief poetics officer at New Kind. Jonathan uses a great presentation to explain that it is story, married with fact, that helps explain our world. I borrowed liberally from what he has taught me to give the students an understanding of why I believe that story matters.

I also chose to use my own life story to explain to them why I care about public policy, as well as why I am dedicated to the daily work of EdNC.

Story might also be a way of reclaiming our own narrative. For me, it has been a way to explain a world that rapidly changed. It has been a way to reframe the betrayal that I experienced, a way to remind myself that the world is still essentially good.

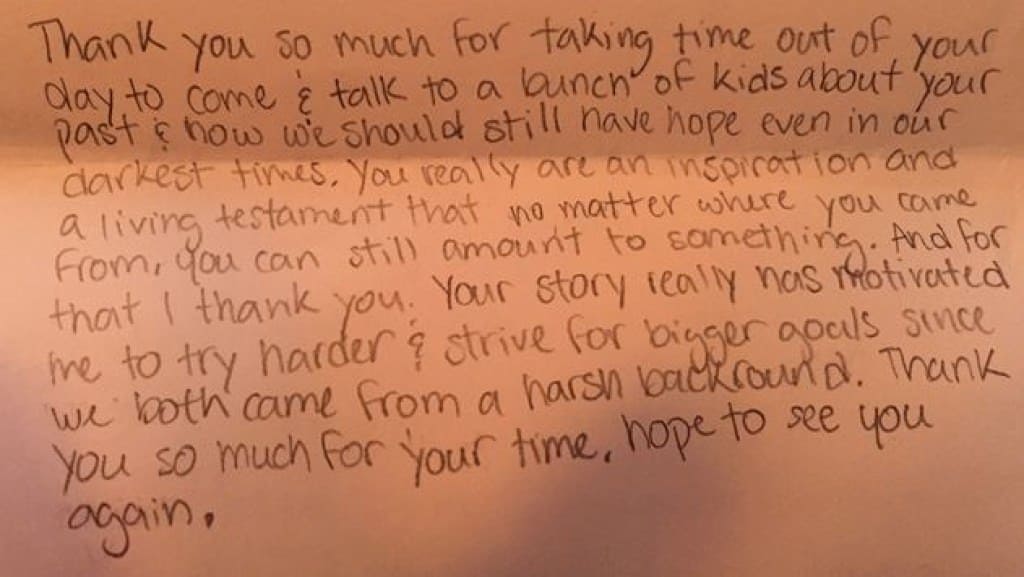

The students seemed stunned, at times, by what I had faced in my life, but it was a student who walked up to me at the end of my session who put it all into words. She said, “Thank you for talking to us like we are adults.”

Surprising. And alarming.

I had simply shared my story. That life has ups and downs. That one life will often contain both unimaginable success and tragedy in equal measure. That we can’t always control the circumstances of our life, but we can determine how we react.

I am not sure that is an “adult” conversation, as much as it is a life conversation. We all face adversity and the Adverse Childhood Experiences study put a face on how much this impacts our brain functioning, health, and how we cope throughout our life. It is important for students to understand that they are not alone in their struggle — even when contemplating suicide as I once did. It is important for students to understand that we are all in this together, woven up in an inescapable fabric of mutuality as Dr. King once declared.

Two weeks ago, the students and I had a conversation about love, loss, and life.

But I learned more from the students than they did from me because I listened too.

I learned about courage from a student who hasn’t seen his mother for years, but said that all he does, he does for her.

I heard harrowing tales of losing a parent, and having to live on as an orphaned teenager.

I saw and felt the struggle to simply be different when it is hard to stand out. To be “others,” to be the “us’s” as Harvey Milk once wrote. It is hard to stand out in high school when uniformity is too often rewarded.

If we are to deal with trauma, emotional stress, and heal one another, then it begins with conversation.

It might begin with a story of what it is to survive the unsurvivable.

It might begin with a message that tells them that they are not alone.

It might begin with saying hello, how are you? and meaning it.

Most of all it begins with an acknowledgement that we see one another across all the different lines that seem to currently divide us. That we really see one another through our strengths and our weaknesses, our pain and our joy.

If we do, then we might have a story worth telling and a state no longer so polarized.

Recommended reading