Early last year, a concerted push began at the state level to transform reading instruction in North Carolina.

Leaders within the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) and members of the State Board of Education had a vision. It wasn’t universally accepted by everyone within either body, but it was shared by a passionate collective. They wanted reading instruction across the state to align with decades-old research about how kids learn to read.

The first chapter of that push ended in September — rather quietly, overshadowed by COVID-19 and pandemic-responsive teaching.

In one school district in the western corner of the state, the fruits of those efforts are starting to take hold. This is the first in what will be a series of stories chronicling a shift in Transylvania County Schools to science-backed reading instruction, often described as the science of reading.

“I want our kids to be great readers,” Transylvania County Schools Superintendent Jeff McDaris said. “And, unfortunately, we still have not cracked that code for how to do that, yet. But I think we’re going to change that.”

State efforts birth a comprehensive reading plan

While our understanding of the science continues to evolve, the body of research spanning the fields of cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and linguistics is not new. In fact, state agency initiatives, like the North Carolina State Improvement Project, have offered training in science-backed instruction for decades.

Nevertheless, balanced literacy remains the predominant instructional approach statewide. The common result? Third-grade reading scores that persistently disappoint.

Leading the efforts to boost scores for DPI was a B-12 Literacy Committee, chaired by Deputy State Superintendent of Innovation David Stegall and Director of K-12 Academics and Innovation Strategy Angie Mullennix. This committee put together a plan for implementing literacy improvement.

Meanwhile, the State Board of Education’s literacy task force, chaired by Ann Clark and Crystal Hill, compiled recommendations for educator preparation programs, curriculum, and professional development.

The task force set an ambitious schedule to complete work in three months — by March 2020. But North Carolina was in the throes of pandemic-induced uncertainty about in-person, remote, and hybrid instruction, and so it was August before the literacy committee and the task force presented their recommendations to the State Board. The recommendations largely went unnoticed.

But DPI’s K-3 literacy team used the work from the task force and the literacy committee to create a Comprehensive Plan for Reading Achievement.

It also gathered input from other DPI agencies, educators across the state, and feedback the State Board offered after monthly reports from then-K-3 Literacy Director Tara Galloway and Regional Literacy Consultant Casey Taylor.

“Our goal was to create an interactive document that would be user-friendly for educators and could serve as the guiding light to illuminate practices aligned with the science of reading,” Galloway said. “In order to impact positive change in student outcomes and disrupt the status quo.”

The State Board approved the plan in September.

State’s reading plan sparks changes in at least one local district

Devoid of fanfare, the comprehensive reading plan nonetheless landed on the desks of district leaders and charter school heads across the state. One of them was the neatly kept desk of Carrie Norris. She is the K-8 curriculum and instruction director for Transylvania County Schools.

Norris opened the plan and very quickly arrived at 10 pages devoted to the science of reading. She read with interest. She had come across some of the research in the plan before, but she had never done a deep dive or seen it presented as thoroughly.

“That’s when I started talking to our instructional coaches and talking about the things that we’re doing,” Norris said. “We have a strong phonics program, but we started talking about the other things we needed to implement, as well as even how to strengthen the phonics things that we’re doing.”

Phonics is a loaded word. While it’s not synonymous with the “science of reading,” it is one of the five components mentioned in the National Reading Panel report released in 2000. But even that report presents an outdated description of the science of reading.

That’s part of the reason the State Board task force and the DPI literacy committee’s work extended beyond initial completion estimates — they spent months trying to craft a definition for high-quality reading instruction to accurately encapsulate the science.

Seeing the definition for high-quality reading instruction in the comprehensive reading plan and pulling the research the report referenced sent Norris on a journey to more deeply understanding the continuum of instructional strategies and practices, as well as the importance of explicit and systematic instruction.

A district ready for change

Transylvania County Schools renewed its emphasis in phonics five years ago. The program it chose — while a piece of a comprehensive, evidence-based curriculum — was limited.

It fell short on some of the instructional components the scientific research supports, like phonological awareness and proficiency, phoneme-grapheme mapping, and morphology.

Meanwhile, some schools in the district still use a balanced literacy approach, which does contain some phonics instruction but also includes other instructional practices (like a three-cueing method) that can hinder students from becoming proficient readers.

Looking at end-of-year state reading scores for their third-graders, district leaders were concerned. Last year, only 57.3% of the district’s third-graders scored at proficiency on the state’s end-of-year reading exam. That put Transylvania County Schools right at the state average. It was a troubling decrease from the district’s performance the prior year, which was 63.8%.

“We’re committed to these [students],” McDaris said. “Our highest priority has to be teaching them to read, because that impacts their ability to perform in every other subject.”

Norris met with her instructional coaches and principals across the district to talk about the changes to come.

“I started working with the principals on looking at the data and showing them how we pick out the weak area for the MTSS process and also really bringing it back to that comprehensive reading plan and pointing back to that research,” Norris said.

A measured plan for gradual implementation

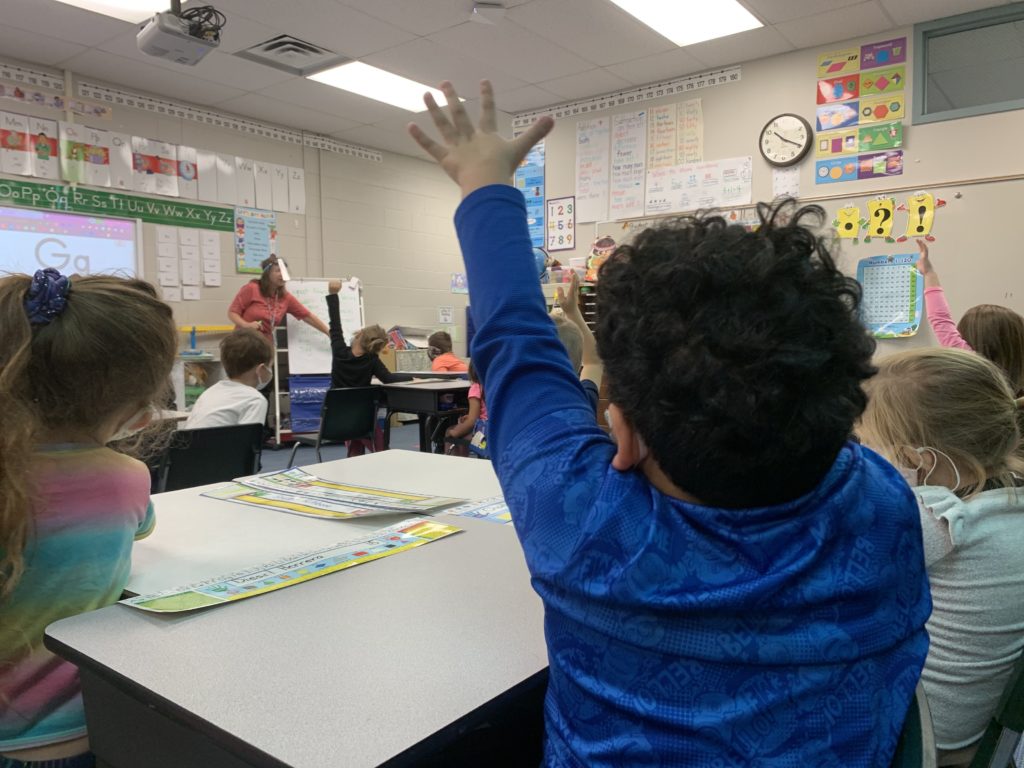

The work in Transylvania County Schools is a blend of training, coaching, and instructional changes.

First, the district will offer a presentation from NCCAT providing an overview of the science of reading for teachers and instructional coaches.

Each teacher will receive LETRS training by spring 2021. Around the same time, the district will invest in 14 employees — Norris, elementary school instructional coaches, and nine teachers — to attend The Reading League’s academy.

The rollout of instructional changes will happen gradually over the course of next year, Norris said.

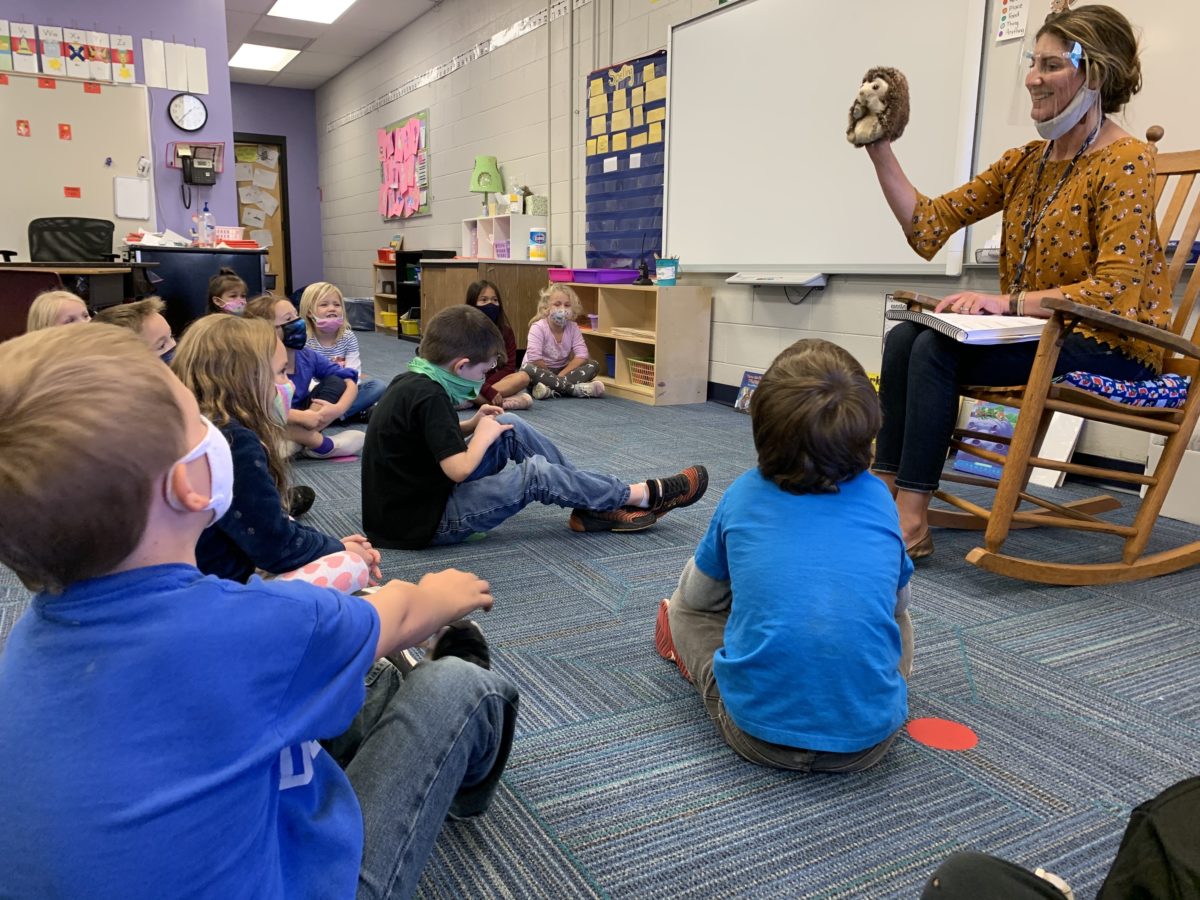

For instance, Rosman Elementary teachers were the first to receive the science of reading overview. Its teachers are also the first using Heggerty, a phonemic awareness program, for kindergarten and first-graders. The school will slowly implement more instructional changes.

Norris wants to make sure teachers have the bandwidth to absorb all the new information and are able to focus on effectively delivering the instruction. That’s especially challenging now, during a pandemic.

“You have to do everything in small doses or they’re totally turning off,” Norris said of teachers, “because their stress level is right now turned all the way up.”

‘I think sometimes we lose the joy of reading’

Norris and McDaris gave the Transylvania County Schools Board of Education an overview of the plan during the November meeting. School board member Alice Wellborn was receptive, but had some reservations.

“I really like all the phonemic awareness, the phonics and all those things, because lots of kids need help cracking the code before they can read,” she said. “But I also know there are some kids, it can really get boring. … I think sometimes we lose the joy of reading. The fun of reading.”

McDaris said he understood that sentiment. He remembers a school librarian when he was little who would challenge him to read books and the joy he got from them.

Loving reading is important, he said, but it’s not possible without first learning to read. And he believes there’s room in the new instructional practices to foster joy while making sure more kids are proficient.

“Let’s stop it,” he said of debates over proper reading instruction. “Let’s realize that there are some definite things that have proven qualities about them. So I hope that when we go more into the ‘science of reading,’ I hope it’s the real science of reading.

“And I am not the expert on that. My job is to hire the very best and get out of the way. We’ve got some good ones down the hall and Carrie Norris is great. So I’m leaving her to jump on it so we can move towards the real science of reading.”