Carolynn Phillips rushed from her day job teaching middle school art to an afternoon coaching girls’ track to earn an extra stipend. On weekends, she had to pick up a few shifts waiting tables to make sure her family could eat. When none of her friends could spare a shift, Phillips spent hours in an art studio rolling hundreds of clay tentacles for octopus statutes to sell.

Summers were filled with work, when she could find it. She remembers one lean summer when she drove six hours from her home in Brunswick County to work an art fair in Atlanta. A week of work netted her a $500 check, well worth the 12-hour drive for Phillips.

“Everything to get by helps,” she said.

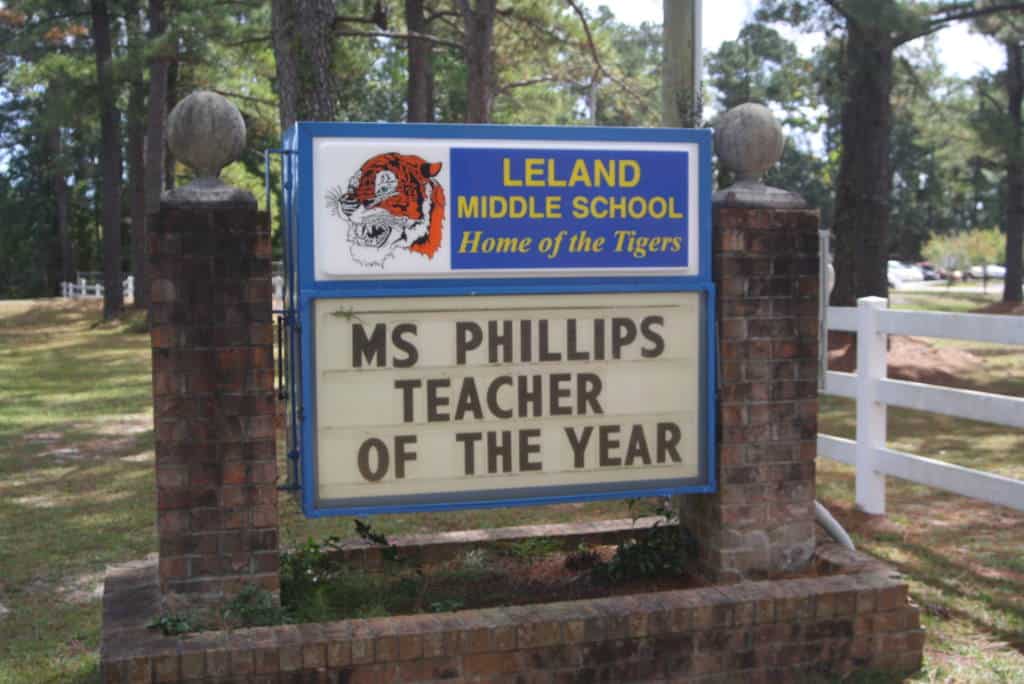

The Leland Middle School art teacher knew she would not be living a luxurious life when she chose to be a teacher more than a decade ago. She wanted to share her love of art with students and stay on the same schedule as her two school-age sons. She thought the retirement benefits were attractive. But she did not expect the pay situation to be so dire.

Even before the 2009 recession, she knew her teacher salary alone could not pay her bills. The rollbacks of state funds on her husband’s band instructor income only put more strain on her already tight budget. In the first year of the recession, they earned $6,000 less than the previous year. Phillips realized she needed to do more to provide for her young family, especially after she and her husband divorced.

She found work in art studios. In the summers, she would find odd jobs, all the while fulfilling her responsibilities as a teacher planning for the upcoming school year.

“I’ve been behind a desk at a retail job laying out lesson plans for the fall,” Phillips said. “I was so tired. I didn’t have the down time I needed. When I wanted to give 100 percent to anything, I just couldn’t.”

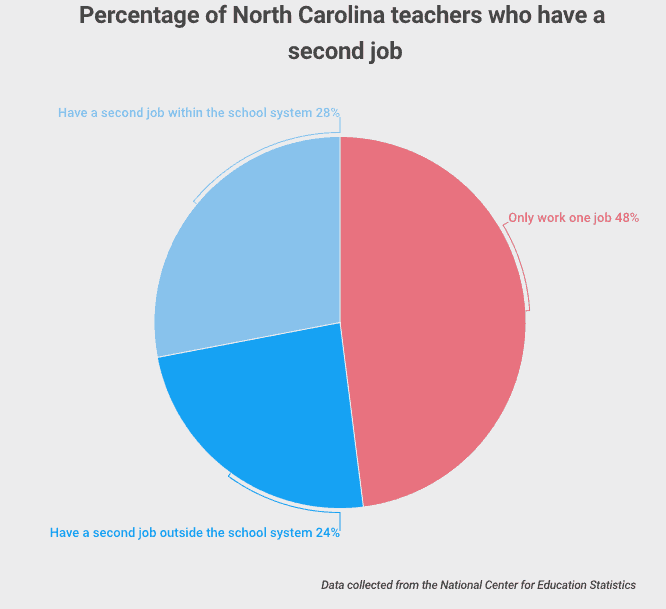

Phillips’ story is not unusual. More than half of all North Carolina public school educators have a second job in the school year, either within the school system or outside employment.

Competing with students for jobs

A survey administered by EducationNC asked teachers what second jobs they worked to make ends meet. The responses ranged from working as a teacher in correctional facilities to dancing as a Zumba instructor and to waiting tables in restaurants.

Third-year teacher Allison Tamney at Leland Middle School struggles to find a steady source of employment outside the school because of the demands of the academic year.

“I’ve been doing odd jobs like babysitting, but it is so hard to get someone to hire you when they know you’re only there for a month and a half or two months. So all my extras are within the school like coaching to get an extra stipend,” Tamney said.

Necessity is the mother of innovation for teachers looking for creative ways to add a second source of income. Because of the responsibilities of their day jobs, educators are faced with limited options. Traditionally, teachers took jobs like tutors for private lessons, allowing for more flexible hours during the school year. During the summer, they compete with their students for entry-level service industry positions or retail jobs.

Leland Middle School biotechnology teacher Scott Monroe echoed Tamney’s struggles in finding a job. When he could not get hired this summer, Monroe took janitorial work at the school when he could.

“They don’t want to hire a bunch of teachers that are only here for a short time. It’s hard to get a job because you’re only going to be seasonal help. You’re overqualified for certain positions. Like my wife is a school nurse, and she couldn’t get a job at Lowe’s,” he said.

Eighteen-year education veteran Jeff Pageau tries to use his qualifications in the classroom for outside employment. When he is not teaching French at Roanoke Rapids High School, he teaches online at Fuel Education, a for-profit virtual school.

“It started as a way to pay back my graduate loans, but now it’s become income that I rely on,” he said.

During the school year, he logs more than his contracted 37.5 hours a week at Roanoke Rapids. In the evenings, he works 20-25 hours a week at the virtual school from home. Pageau enjoys the flexibility the work affords because he can plan lessons and grade papers while instructing his online students. But if circumstances were different and his day job provided more compensation, he would not be trying to juggle two jobs at once.

“I would leave it in a heartbeat if I could,” he said of the online work.

Michael Waters has taught in North Carolina since 1989. Over the course of his career, he has taught night classes at Western Carolina University, played the bagpipes at weddings on weekend, and worked as an English interpreter for Spanish-speaking students to make ends meet. He thought about changing careers, but feels a sense of responsibility to his students.

“I feel a commitment to the Hispanic community,” the Macon County teacher said. “I am now teaching the children of my former students.”

Bill Long and his wife both teach at Iredell-Statesville Schools during the day and both work second jobs to keep food in the fridge on nights and weekends.

“I have been working at the local YMCA for four years. I’ve worked there as a personal trainer and wellness coach,” he said. “A teaching check every month didn’t cover everything, especially with a wife and kids.”

Neither he nor his wife thought they would ever qualify for government aid with teaching degrees, but during the 2009 recession, the Longs qualified for Medicare and food stamps.

Lagging behind on teacher pay

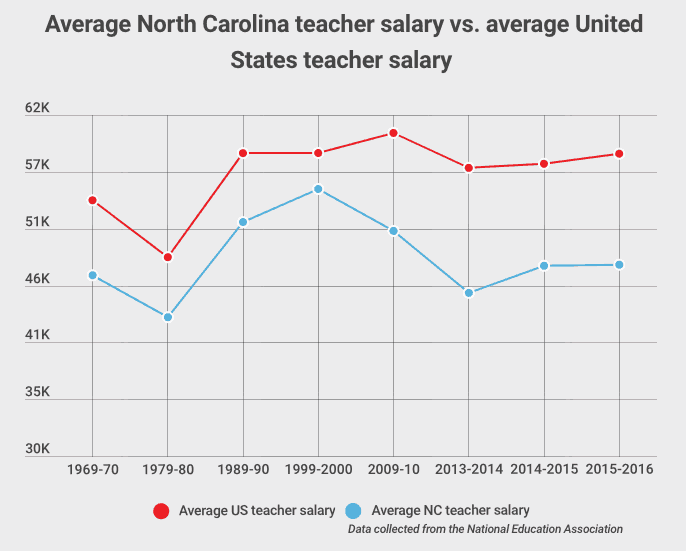

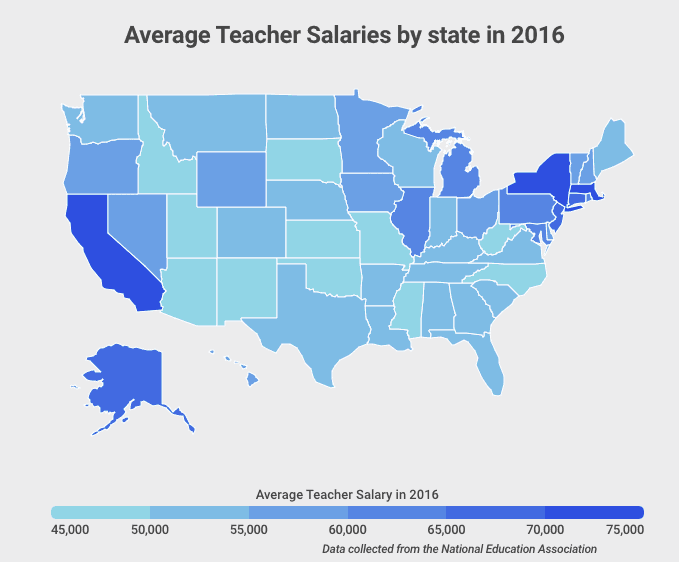

North Carolina ranks 41st in the country for average teacher pay, according to the latest numbers from the National Education Association. North Carolina’s average annual pay of $47,941 lags nearly $10,000 behind the national average. During the national recession in 2009, average teacher pay in the state fell faster than the national average. Increasing teacher pay has been a legislative priority for several decades.

Superintendent Mark Johnson sees a link between quality education and teacher pay. “We need to treat teachers like professionals and the first step is in pay,” Johnson said to EdNC during his campaign last year. “Pay is very important but it’s not the only factor. We also need professional development.”

The new state budget calls for an increase in teacher pay, but it will still fall short of the $50,000 average teacher salary goal set by legislators.

Incremental increases have not freed teachers from having to work second or even third jobs. The cost of living has steadily increased the last few years. Despite claims of change in Raleigh, teachers still feel the effects.

“It becomes mainstream talk when elections come around, but we aren’t seeing many results,” Phillips said. “If I wasn’t a dual income family, I would have the same struggles now that I did during the recession. The raise didn’t chance that at all.”

Burden shifts to local leaders

Local school districts and cities are left to scramble to make the commitment to teaching not be a commitment to poverty for their public educators.

The Durham Public School Board plans to build 24 affordable apartments for teachers in their district where the price of rent is outpacing teacher pay. This past summer, Brunswick County Schools became the first district to hold a weeklong “teacher academy” in August that allowed every teacher a week of paid professional development.

“We really wanted our teachers to feel valued and appreciated and improve the quality and efficiency of planning instruction,” assistant superintendent Deanne Meadows said.

By most accounts, it was a successful pilot program. Teachers were paid for a full week of work, and it even freed more veteran teachers like Phillips from having to work in the summer. But because the planning week pay was scaled to teacher tenure, more veteran teachers like Phillips received greater pay than younger teachers. Younger teachers like Allison Tamney appreciate the efforts from the district, but they are still hurting.

“It wasn’t big for me because it’s based on year, so that’s an obstacle. I’m in my third year, and I’m very struggling,” Tamney said.

“I need the money.”

Things are different this year for Phillips. Now in her 12th year, she will not have to work on the weekends to make ends meet for the first time in a decade. She can afford the financial freedom because she moved in with her boyfriend this past year. Instead of working, she spends weekends with her boyfriend and two sons, now 15 and 9.

Even during all those years of burning the candle at both ends, she did not lower her high level of expected excellence from herself and her students. She did not let her hectic work schedule get in the way of winning multiple teacher awards, including the Brunswick County Schools Teacher of the Year distinction this October.

“You have to multitask times 100,” she said. “I love my job, bottom line. I really do. I love interacting with these guys. People are scared of middle schoolers, but they are so fun, and I think they’re great.”

Yet even with the awards and accompanying stpiends, there is a careful financial balancing act. Phillips is grateful for the recognition, but if this was another time in her career, she would have to turn down the accolades because the additional responsibilities would interfere with her weekend work.

“It’s a huge honor and I’m excited to take this role, but there’s always going to be that struggle of figuring out when I can balance my job at Leland Middle, the extracurriculars I have and now being on the school improvement group and leading the teacher advisor counsel. It’s a lot. I’m confident but I can imagine if I had to work a weekend job, I couldn’t do it. I would have to tell them I couldn’t do that awards. I need the money.”