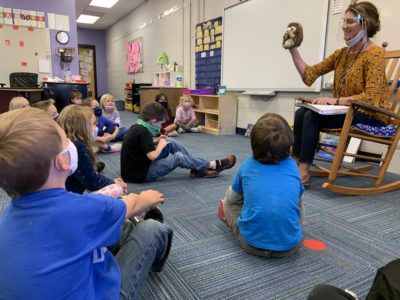

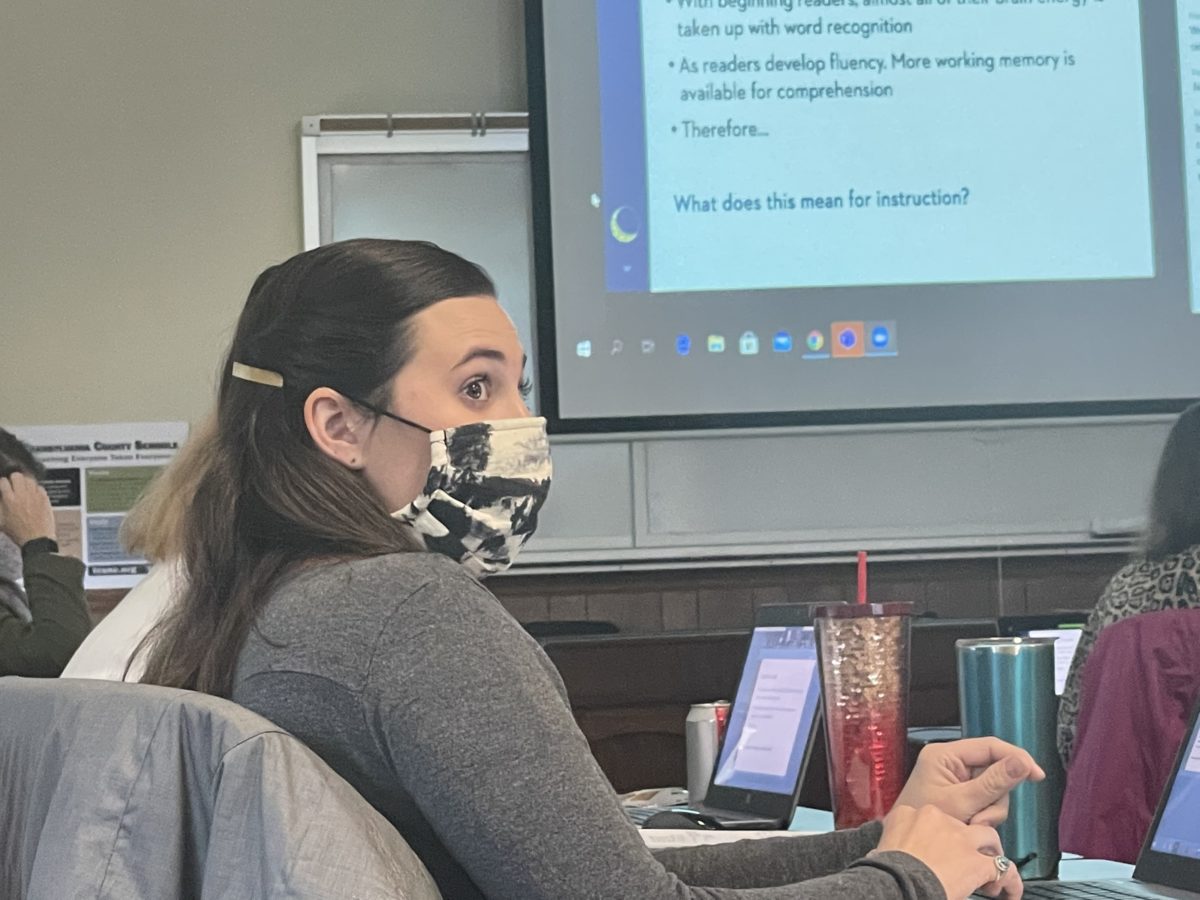

About a dozen early-grade educators gather in a room of the Transylvania County Schools central office. Transfixed, they stare at a slide projected to the front of the room that shows data funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Up to 80% of students in every class can learn to read, the data on the slide say. Add another 15% who can learn with specialized interventions, the slide suggests.

Eyes bulge as the slide adds the numbers to 95%. Some eyes are wide with shock. At least one set of eyes hides a little bit of pain.

“I did the math, and if you have 20 kids in your class, that 5% is just one kid,” said Kim Moore, instructional coach at Brevard Elementary School. “That means that 19 of your kids should be on grade level.

“Nobody’s there — and that’s the thing. It hurts to hear it, because it’s like, what have we done?”

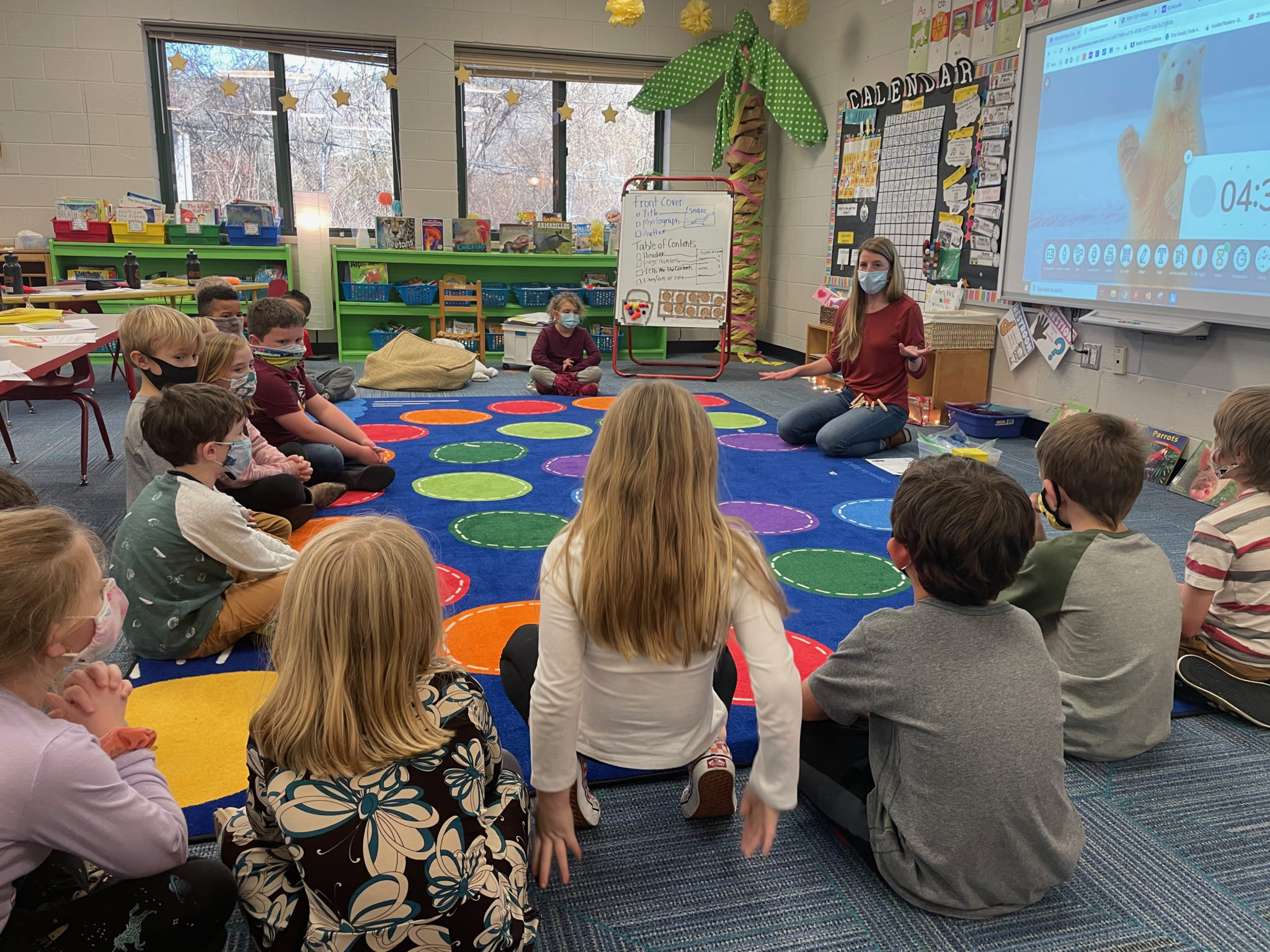

In Transylvania County Schools (TCS), the district is focused on aligning reading instruction with the science of reading, a body of decades-old research on such subjects as how kids learn to read and best instructional practices. But it has become apparent that teacher knowledge in that science is widely varied.

Many say they didn’t learn it in a college of education. Some said they weren’t explicitly taught any specific approach to teaching kids to read.

“I was a math concentration, so maybe that was some of it,” Rosman Elementary first-grade teacher Haley Dawson said. “But if you think about it, in elementary education, everybody has to teach reading. And I do remember my first year in kindergarten, being mind blown. So that leads me to believe that I just didn’t have that experience in college.”

Learning it now is harder because she has a class full of students and a head full of approaches she’ll now have to abandon. Other teachers in the district share this sentiment.

“You’re preparing lessons for students and, at the same time, learning things that can change how you’re doing things,” said Kim Geer, who teaches first and second grades at T.C. Henderson School of Science and Technology.

Teacher knowledge about the science of reading varies

Many teachers in TCS say the curriculum at the schools where they started teaching heavily influenced how they teach reading. Many early-grade classrooms across North Carolina use “whole language” or “balanced literacy” curricula, which include teaching methods not supported by scientifically based reading research.

Regardless of which approach one favors, several districts have started to align instruction with the science of reading — a direction signaled by the State Board of Education last year. In the coming weeks, the General Assembly is expected to consider legislation that would require it statewide.

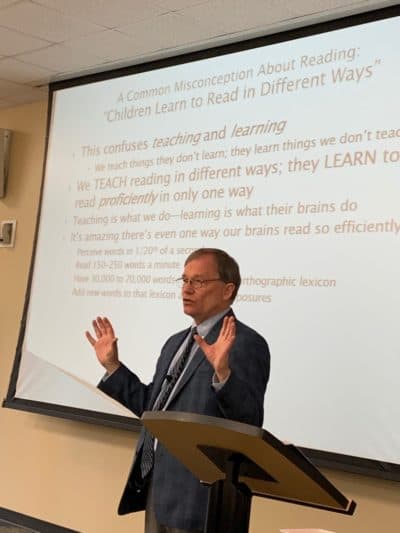

But the science of reading isn’t a quickly mastered program or off-the-shelf curriculum. It isn’t a fad or some phonics program. It’s a term referring to vast amounts of scientific research that span several disciplines.

There is cognitive and neurological research on how the brain learns to read. There is also a large volume of clinical research on instruction. What teachers need to know about the science of reading has to cover both of these things — the science of how one learns and what we know about best practices for implementation and instruction.

It’s a lot to take in, especially through a series of professional development opportunities while a teacher is already on the job.

“They all start to blur together,” Dawson said of the trainings. “There’s just so much, and there’s a lot going on right now. … But I feel optimistic about where we are with reading — much more optimistic than I felt at the start of school. I like where it’s headed.”

Getting everyone on the same page means a delay in full implementation

TCS Curriculum Director Carrie Norris said she’s moving at a slow, but deliberate, pace for fully implementing science-based reading instruction across the district.

She wants to focus on providing training and retraining given district teachers’ varied levels of grounding in the science of reading.

Norris said she hopes the trainings will develop teacher knowledge this year, and she plans to sit with teacher leaders and her four elementary school instructional coaches over the summer to talk about specific designs for implementation.

It’s a good goal, says Joy Cantey, the literacy director for Guilford County Schools. But Cantey cautions against expectations being too high. Her district started focusing on science-aligned instruction about four years ago. As in TCS, teacher knowledge of the science varied. The district is still working toward full implementation.

“It takes time, and you have to be patient and remind teachers to be patient with themselves,” Cantey said.

But it can start happening right away, she said, and districts can start seeing progress in student outcomes before full implementation.

Moore, the instructional coach at Brevard Elementary, said she appreciates a steady, deliberate approach.

“We’re all building houses, but if we don’t build the same foundation that is just as strong for each house, some of these houses aren’t going to last,” Moore said. “Everybody’s house is going to be different, because every teacher is completely different and that’s fantastic. But the foundation has got to be the same, and super strong.”

A teacher’s experience of how she learned to teach reading

When Dawson graduated, she said, she didn’t feel prepared to teach kids how to read.

“I definitely was learning it on the job,” she said. “Those first two years, I made the most mistakes ever.”

She learned by relying on her school’s curriculum, Units of Study, which is part of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project program founded by Lucy Calkins. It is a balanced literacy program.

Dawson also learned from the other kindergarten teacher at her school, she said. That teacher’s experience drew from the Units of Study curriculum, so she coached Dawson on balanced literacy strategies like using pictures and context to cue students to figure out a word, using leveled readers during guided reading blocks, and practicing the “Lucy Calkins Super Powers.”

All three of these strategies are on their way out in TCS, which underscores the importance of every teacher and administrator understanding the science. Veteran teachers influence beginner teachers through collegial coaching, and administrators and district leaders have a huge impact by choosing curriculum.

The curriculum is important because not every school empowers its teachers to break away from it.

That’s how Dawson felt five years ago at the first school where she taught. It was Moore’s experience, too. Moore has taught reading for 24 years, including 16 in the classroom.

“I have an enormous amount of background, and I’ve always had these questions about how we are teaching reading,” she said. “But [administrators] would always just say, ‘No, this is how we do it.’”

District’s approach has helped balance excitement and discomfort

The TCS approach to revamping instruction has been inclusive, with communication and feedback encouraged up and down the chain. There is a hopeful spirit even though it will take some time to lay a foundation.

“It’s very reviving,” Moore said. “It’s something new, but not really. I guess it’s just a different way to think of things. So I’m super excited about it.”

As exciting as it is for her, for the three other elementary instructional coaches in the district, and for many teachers, there are a handful of teachers who describe the experience as “overwhelming.”

Coaches stop short of saying these teachers are resistant. But district leaders are listening, talking about concerns, and trying to build teacher capacity to boost acceptance.

“I think that’s been the sentiment from veteran teachers who have heard all kinds of things over the years,” said Ann Rich, instructional coach at T.C. Henderson. “Every year, there’s a new thing, like, oh, actually we have to focus on this and that. And they’re kind of like” — she demonstrates their reaction as her face goes blank and then a hint of skepticism pinches her eyes.

“It just becomes a fog over time, and they just kind of pick and choose,” Rich said.

Kim Geer says she’s one of those teachers, amiably skeptical about change. She says it’s not resistance. The word she chooses is “careful.”

The scientific reading research wasn’t taught at her undergraduate or master’s in reading programs, she said. And for seven years, she was a specialist in Reading Recovery, a balanced literacy program.

Moving onward — soon, some teachers hope

As a Reading Recovery specialist, Geer said she had about 70% to 75% of her kids reading on grade level.

“Going through this science of reading movement that we’re in, I told them I’m going to have to do some research,” she said. “Because everything they’re telling me — and there are a lot of things they’re telling us — is contradictory to what I had been taught and learned to love as a Reading Recovery teacher.”

After a few months of training and doing her own research, she said, “It’s kind of hard to just dispute the evidence.” She knows that her four-student class sizes as a Reading Recovery specialist helped her achieve results. And if knowledge in the why and how of the science of reading will help get better results with larger classes, she’s on board.

“It hurts a little,” Geer said. “It’s kind of an ouch in a few areas. But that’s … you know, growing always pinches somewhere.”

Her biggest question now is: How long until the district has more detailed plans and supports?

“I’m ready for more formal direction, I guess,” Geer said. “Give me a lesson plan format; give me a daily schedule. What should this look like?”

That’s coming, Norris said. First, she needs the foundations for all the homes to be strong. It could take at least the rest of the school year just to get everyone’s knowledge base to her level of satisfaction.

“We have to get them the knowledge first,” Norris said. “We have to give them the knowledge they need so they can make knowledgeable choices when they’re in charge of doing this in their [classrooms].”