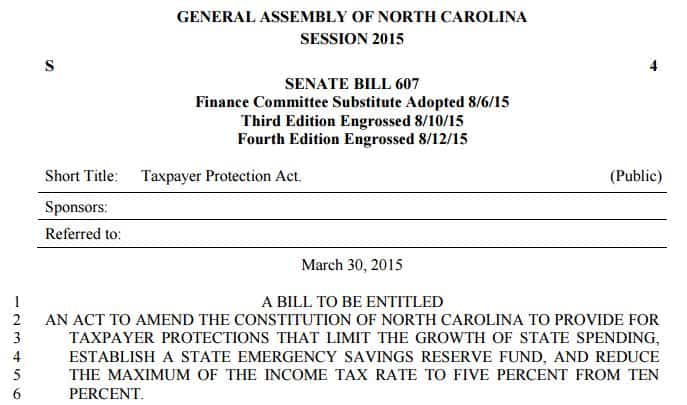

As North Carolina’s legislative session (presumably) winds down over the next couple of weeks, it seems increasingly unlikely that the cap on state spending growth and other provisions of the proposed Taxpayer Protection Act will pass this year. The Senate approved the measure a few weeks ago. It would place the TPA on the ballot as a constitutional amendment for voter approval. The House didn’t follow suit.

It’s still a live option for 2016, however. Inaction by the House doesn’t mean that most members oppose the idea of amending the constitution to limit spending growth and require the accumulation of healthy rainy-day reserves to hedge against natural or fiscal disasters. Instead, members have simply been focused on other matters — including the passage of a state budget — and aren’t entirely sold on all the details of the bill passed by the Senate.

Neither am I, as a matter of fact. But I do believe constitutional protections of the interests of taxpayers should be improved. I also think that those opposed to the Taxpayer Protection Act have been remarkably unpersuasive. They’ve invested much time and effort trying to convince North Carolinians that the idea is foreign to our state, that it is being foisted on them by the American Legislative Exchange Council or other out-of-state activists seeking only to replicate Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR).

Their claim is incorrect. I should know. I was involved in the effort to craft the first iteration of the Taxpayer Protection Act, which was introduced at the General Assembly in 1993. That measure, in turn, was inspired in part by a 1991 bill that would have limited state spending growth in a new fiscal year to the amount of state revenue collected during the previous calendar year. While that earlier bill didn’t pass, one of its components did — the creation of a formal rainy-day fund, albeit by statute rather than constitutional amendment.

Furthermore, North Carolina’s TPA isn’t a carbon copy of TABOR. The two measures do different things. Most importantly, TABOR prevented the large savings reserve that TPA requires (and that North Carolina desperately needs).

Close observers of state politics will recognize many of the names involved in the TPA debates of the early 1990s. The original budget restraint and rainy-day proposal in 1991 had two main sponsors, Bill Goldston and Art Pope. Goldston, a powerful Democratic senator, later became one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit successfully challenging former Gov. Mike Easley’s decision to raid the Highway Trust Fund to balance the state budget during the 2001-02 fiscal crisis. Pope, a Republican House member who served as joint caucus leader during the 1991-92 session, later served as Gov. Pat McCrory’s budget director (and chairs the board of the family foundation where I serve as president).

In 1993, Rep. Robert Brawley of Iredell County was the primary sponsor of House Bill 960, the Taxpayer Protection Act. Its main provision was to subject most tax increases to voter approval. Brawley’s co-sponsors on House Bill 960 included future congressman and state Republican chairman Robin Hayes, future House Co-Speaker Richard Morgan, and future felon Michael Decker. The following year, 1994, a new version of the TPA added the idea of capping the annual growth of state spending to some combination of inflation and population growth.

Outside the General Assembly, one of the TPA’s strongest champions during the 1993-94 session was a recently created grassroots organization called North Carolina Taxpayers United. Among its founders were two future U.S. senators: Richard Burr, then a businessman who would win election to the U.S. House in 1994, and Rand Paul, a medical student at Duke University who later moved to Kentucky and went into the “family business” as it were by winning election to the Senate in 2010. Other members of the group’s advisory board included future House Appropriations Co-Chair Jim Crawford, a Democrat, and future congressman Walter Jones Jr., a Democrat-turned-Republican.

I don’t expect today’s critics of the Taxpayer Protection Act to know this history. Most of them lived elsewhere back then. I promise not to hold that against them.

Editor’s Note: The John William Pope Foundation supports the work of EdNC.