Editor’s Note: Robert’s documentary, Anchored in Tarboro, is the first in a series for EdNC on the strength we see in our rural places. At EdNC, we deeply embed in communities because our schools are anchor institutions, but we’ve realized so are churches and nonprofit organizations and restaurants. Join us in getting to know our rural communities.

In rural places, folks are more spread out, so they have to reach out a little further to lean on each other.

Take a look behind the scenes with me.

In December 2018, I began making occasional trips to Tarboro. My goal was to meet these people and create a video about them. As I explored the area, it became clear that the work here was so extensive that capturing it all in one video would be tough.

In the 2010 Census, Tarboro’s population was 10,856. Edgecombe County was the sixth poorest county in North Carolina. But there is so much hope.

Craft beers and conversation

I spent the most time with Inez Rubistello, known to most people in Tarboro as “Inie.” She’s a Tarboro native who moved back home with her husband, Stephen, who’s from New Jersey. They met in New York City working at Windows on the World, the restaurant that once sat at the top of the World Trade Center.

Together, they operate two local businesses: a restaurant called On the Square and a brewery called Tarboro Brewing Company. The duo opened the brewery after they realized On the Square, which offers food and wine choices for a more refined palate, was too exclusive for some in the community.

Inside Tarboro Brewing Company, you’ll find a large open layout complete with air hockey and foosball tables, a bar, plenty of chairs, and a chalkboard wall that doubles as a menu. Hand-drawn doodles accompany the listing for local brews like Nana’s Roof and Small Town IPA.

In this room, the brewery hosts a monthly community meeting called “Cultivating Change.” A panel of speakers will tackle a topic — on one of my visits, for example, it was food and dieting — and then begin a dialogue with the community members in attendance.

The event is free and everyone gets a free drink ticket, but you don’t have to drink. In fact, you don’t have to buy anything at the brewery — folks are encouraged to bring food from elsewhere and just sit for a while.

Inez hopes the meetings will generate conversations between the politically opposed, but noted the tendency of similarly-minded people to attend. The event inherently attracts a crowd that cares about things like inequality, racism, and poverty.

It starts in the home

Sitting in that crowd, you’ll often find a pair of researchers well known in the community. Seth Saeugling and Vichi Jagannathan relocated to Tarboro from the Bay Area and created a nonprofit organization called Rural Opportunity Institute.

During their time in San Francisco, the duo had learned more about a study known as the ACE study. ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) — such as experiencing violence or abuse, or losing a family member — are correlated with a plethora of negative health outcomes as an adult. Your ACEs score is determined by your answers to these 10 questions, and high scores were correlated with everything from heart disease and stroke to depression.

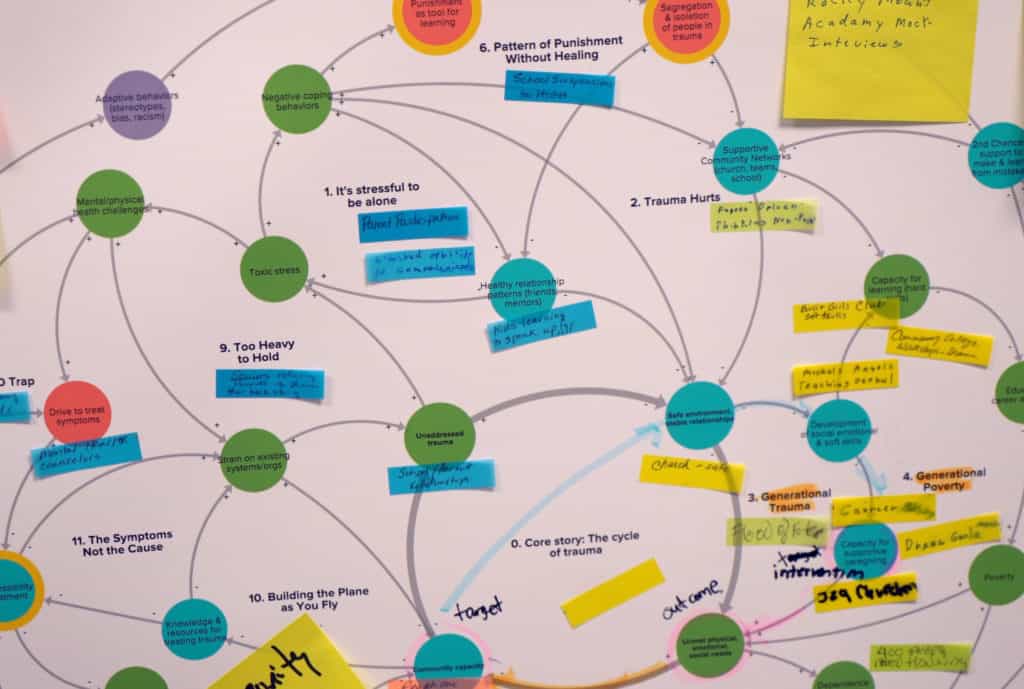

With this knowledge in mind, Seth and Vichi created Rural Opportunity Institute with the goal of ending generational cycles of trauma and poverty. First they sat down and interviewed members of the Edgecombe community to learn more about their particular struggles. Then they used these interviews to generate a map of issues and an action plan for the community.

A big part of that plan is shifting away from punitive measures toward restorative justice, starting in the school system. The hope is to mitigate out-of-school suspensions, which have often led to students getting behind and giving up on school altogether as a result.

In response, Rural Opportunity Institute piloted biofeedback programs for local students and prisoners. At Pattillo Middle School, students prone to misbehaving were placed into the program, where they learned breathing techniques to calm down. Teachers saw better behavior as a result.

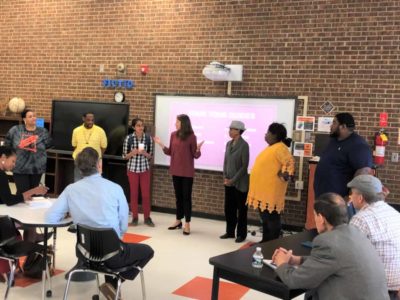

The organization also hosts regular meetings where the community discusses the work and ultimately holds Seth and Vichi accountable to their plan of following the community’s wishes.

When suspensions turn into sentences

At one of these community meetings, I met a man named Na’im Akbar. His own nonprofit organization, House of Help, is focused on aiding students and formerly incarcerated people in the community.

Na’im was incarcerated twice. With his college education, he was adept at speaking with both the people held in prisons and the prison staff, and often found himself representing inmates in an attorney-esque position.

Now, he uses that ability to do something similar for school children. When suspended students are called in for a disciplinary hearing, parents sometimes enlist Na’im to sit in on the meeting, helping the parent navigate a world of terms and policies they don’t fully understand.

Faith helped Na’im stay out of prison for good. As a practicing Muslim, he said he has no problem working alongside the mostly Christian populace of Tarboro. The important thing, he said, is removing the barriers between us that prevent great work from getting done.

My time in Edgecombe County was too short to cover all the innovative initiatives there. For example, Richard Joyner operates the Conetoe Family Life Center, which grows fresh fruits and vegetables and offers community education on nutrition.

North Carolina’s 2019 principal of the year works in Edgecombe County. And a group of K-12 educators near Tarboro recently created a radical new public school model that warranted an entire EdNC short documentary of its own.

These initiatives cover a broad spectrum of the issues we face as human beings. What they have in common is a culture of listening. Why do people believe what they do? What would best help people experiencing poverty and trauma? How do students want school to look? In Tarboro, people are asking, people are listening, and people are changing.