According to studies stemming from the early 1980s and continuing on to the most notable research conducted with over 17,000 participants by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997, researchers have found that there is no longer any doubt that violence and chronic exposure to toxic stress disrupt the process of normal childhood development (Perkins & Graham-Bermann, 2012). These experiences alter the architecture of children’s brains in ways that threaten their ability to achieve academic and social competence, and left unattended, these can affect health and well-being not only of children, but adults, as well (Karr-Morse & Wiley, 2012). These types of traumatic childhood experiences are now referred to as Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, and they can be categorized into the following areas of reference:

- Abuse: Physical, emotional, and sexual

- Neglect: Physical and emotional

- Household Dysfunction: Mental illness, incarcerated family member, mother abused, substance abuse, and divorce (Craig, 2016)

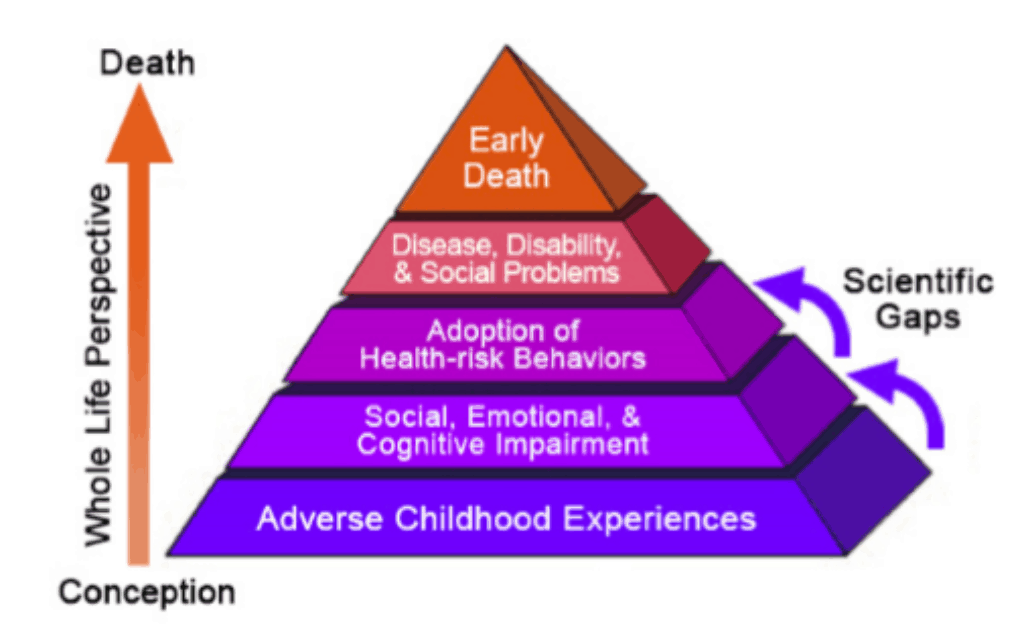

In the original ACEs study of 17,000 participants, 67 percent of those adults experienced one ACE, while 12 percent experienced four or more ACEs. The results of experiencing one or more ACE as a child resulted in negative outcomes, and eventually to early death. The revised ACE pyramid shows that adverse childhood experiences lead to social, emotional, and cognitive impairments, which then result in the adoption of health risk behaviors. Those behaviors then lead to disease, disability, and social problems, which can lead to early death (Craig, 2016).

What’s the good news? Based on what we now know about brain development and the brain’s ability to adapt throughout the human life span, we know that there is hope that the effects of early trauma can be reversed later in life (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2009). What does that mean for educators and the students they serve? With the right amount of intervention, support, and care, students who experience one or more ACEs can still have positive, successful school experiences and productive lives.

Signs that students need help, due to ACEs, may include:

- Problems with communication & language; depressed vocabulary

- Problems regulating emotions

- Problems organizing their thoughts or belongings

- Problems with hyper-arousal or low-arousal (they don’t have control over it or know how to regulate it)

- Problems sustaining their attention or effort

- Problems acting before thinking

- Problems with working memory

- Inability to control inhibitions/distractions

- Lack of empathy for others

- Problems with forming bonds

- Resistance of adult engagement or attachment too quickly (indiscriminate proximity seeking). (Craig, 2016)

Teachers can help support students with ACEs by:

- Learning how to recognize trauma flare-ups

- Helping children identify self-soothing behaviors to relieve their stress and feel better

- Helping students self-monitor and self-reflect

- Communicating with administrators and team members about students’ needs

- Attending support meetings to discuss students’ needs and tiers for interventions

- Working with a school team to “normalize” the effects of working with traumatized children

- Co-planning with other teachers and team members to address social needs and embed dialogic teaching in lesson plans (Craig, 2016)

Schools can help support students with ACEs by:

- Creating a system of tiered interventions and supports for students who experience trauma

- Establishing partnerships with local mental health agencies

- Training teachers to differentiate for all students’ needs

- Training teachers on positive behavior interventions and supports as part of their classroom behavior management plans

- Supporting teachers with Stress Management practices and structures to be utilized throughout the day

- Creating policies/procedures for confidentiality of students’ records and needs (Craig, 2016)

Schools can become healing environments for troubled children when teachers and administrators understand the role of the environment in neural development and the anomalies caused by early trauma histories (Craig, 2016). It is our role, as educators, to make these students’ school experiences as supportive and nurturing as possible.

References

Craig, S.E. (2016). Trauma sensitive schools: Learning communities transforming children’s lives, K-5. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Karr-Morse, R. & Wiley, M. S. (2012). Scared sick: The role of childhood trauma in adult disease. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books. National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2009). Child traumatic stress introduction information sheets. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org

Perkins, M. & Graham-Bermann, S. (2012). Violence exposure and the development of school-related functioning: Mental health, neurocognition, and learning. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(1), 89-98.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the NC New Teacher Support Program September 2018 newsletter. It has been posted with the author’s permission.