Share this story

|

|

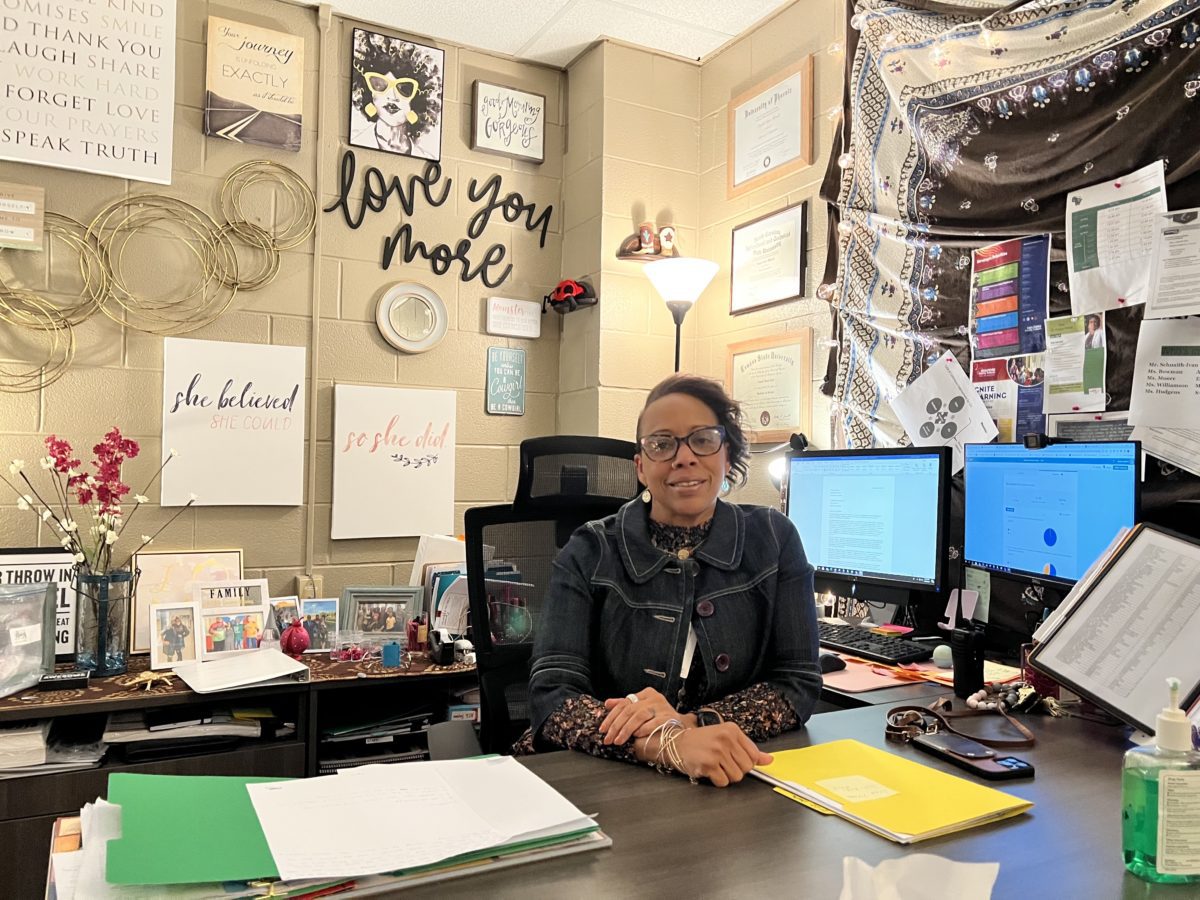

Angela Monell never forgot her first experiences in a classroom. Teaching at a private school for students with learning differences, she was blown away by the school’s approach to discipline.

The student population didn’t fit squarely into the education system’s box of what proper behavior looked like. So, instead of using discipline to punish, the school used discipline to educate and support.

“And I always remember thinking, if I ever run a school, I would love for that to be a part of my school,” she said.

Monell started running her own school last year when she was named principal at Southwest Guilford High School. But integrating restorative practices there actually began after she was named assistant principal in 2016. Today, the school has seen in-school suspensions reduced, attendance increased, and grades raised.

“We have people who focus solely on our discipline and restorative practices,” Monell said. “We’ve changed, really, how we approach (discipline) and we’re seeing a big difference.”

Keeping kids in class is critical

A lot of research tells us chronic absenteeism has a deeply negative impact on academic performance, graduation rates, and postsecondary outcomes.

Often, efforts to combat persistent absences are directed at parents — but what about when the school is keeping kids out of class? What about when schools are so focused on punishing bad behavior that the same kids keep missing class because of suspensions?

“Are we thinking about what’s going to be the best outcome for these kids?” Monell said. “What are we trying to teach them? Are you trying to teach them some skills on how to resolve things, or are we trying to just punish them?”

Those are the questions Southwest Guilford High School confronted and addressed, and as a result, it’s recreating a culture of belonging, improving emotional regulation, and increasing attendance. And how they’re doing it is worth paying attention.

In-school suspension looks a lot different now. Not only is it less utilized, but when it is used, its purpose is to restore students to the classroom with new tools.

“I’ve always kind of had my own little justice system in my class and thinking very critically about my classroom management, how my classroom management was responsive to students’ behaviors,” Monell said. “Not always saying, oh, this kid did this so I’m gonna give him this consequence. It’s more, let me think about how I can get creative with my own discipline in my classroom.”

While some districts nationwide are trying to incentivize students to come to class by giving away cars, Southwest Guilford is taking a whole child approach — making critical decisions based on teaching behavior more than punishing it.

Here’s how it’s done

When Monell became assistant principal at Southwest Guilford in 2016, she started having conversations about equity with her principal.

In a school with more than 70% white teachers, she wanted to address disciplinary practices that resulted in mostly Black students being referred to in-school suspension. At that time, the school called in-school suspension “Behavioral Instruction Program.” The students called it “Blacks In Prison.”

“I’m not okay with that,” Monell said.

She began by going through the school’s handbook. Many of the terms for disciplining students felt vague — like Rule 6: disrespect.

“What’s disrespectful in one household might not be in another,” Monell said. “So, did the students really know what we were expecting?”

Monell and other school leaders committed to redesigning both in-school suspension and all disciplinary practices to focus on educating students on expectations and guiding them to excellence in the classroom.

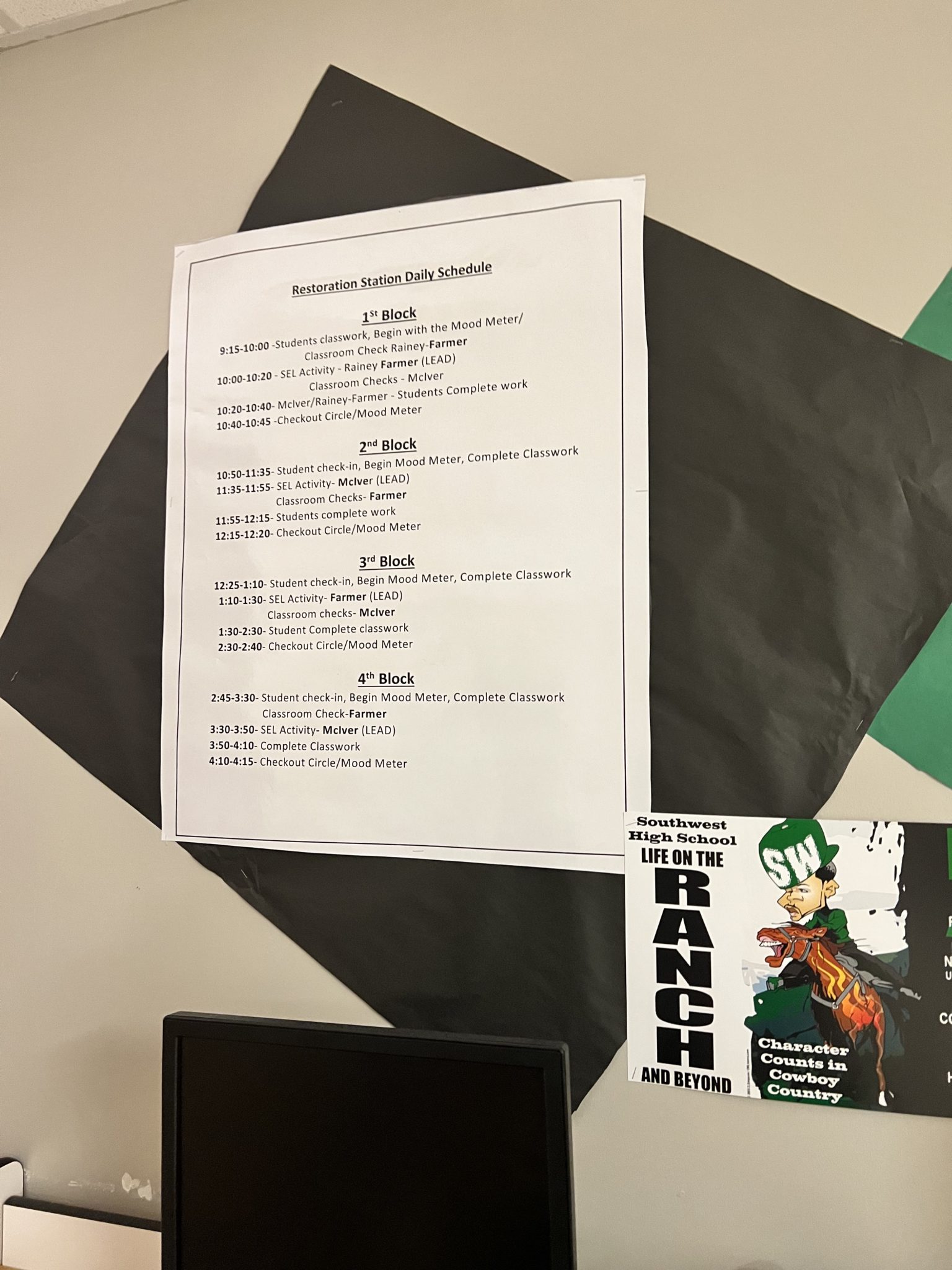

The first step, she said, was renaming and reframing in-school suspension. They now call it Restoration Station (RS), and its once-punitive purpose of housing students who had misbehaved is now replaced by a series of restorative practices.

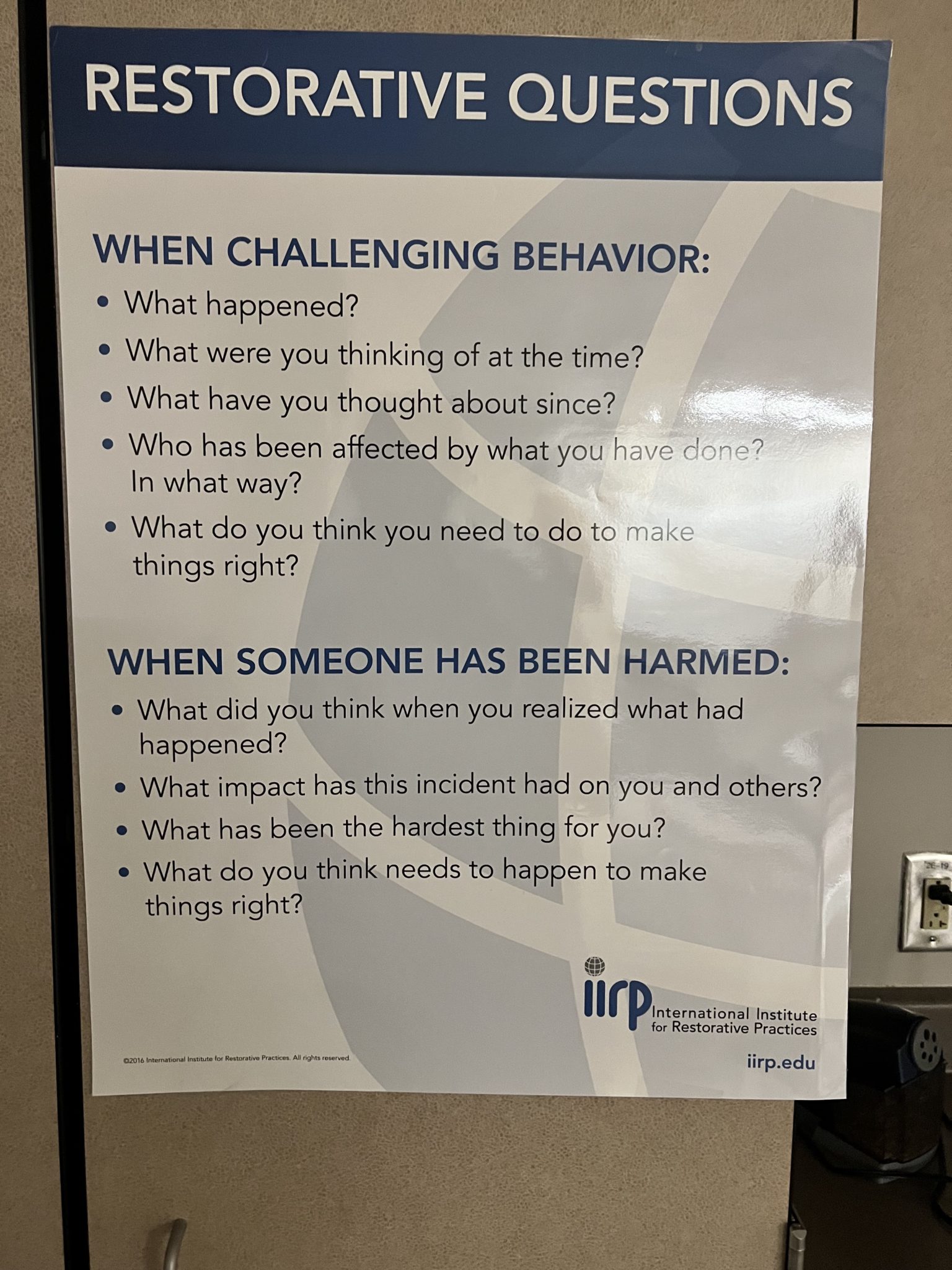

For one thing, students don’t just sit quietly all day. They transition through a series of lessons every time the school bell rings, including social-emotional learning lessons and something called restorative conferences.

“There’s some movement there, and the kids know what’s happening at each part of the day,” Monell said.

Much of that is addressing the incident that got the student in Restoration Station.

“We need to start educating kids on what respect looks like in different places,” Monell said. “If you’re there for non-compliance, all right, how were you non-compliant? And how do you not be non-compliant?”

The restorative model the school uses looks at engagement happening in one of four ways: Are you engaging to in a punitive way, for in a permissive way, not in a neglectful way, or with in a restorative way?

The first school year the school implemented the model was in 2017-18. The next year, in-school suspensions dropped about 31% and out-of-school suspensions dropped about 17%.

It’s primarily for teachers to examine how they are engaging with students, and for students to ask how they’re engaging with each other. But teachers are finding that it helps them in life outside the school building.

“I could be in church and I’ll be like, I’m in my ‘to’ box,” said RS teacher Deidre Farmer. “But it works anywhere. It makes you become one with yourself and ask, okay, what am I feeling? Because I don’t want to make the situation escalate so I need to transition to my ‘with’ box so I can be more restorative.”

Teachers are giving it a shot, and buying in

Amanda Vanscoyk was not excited when she started hearing about some of the changes.

“I was not bought in on the SEL/restorative practices. I thought it was a bunch of nonsense,” the English teacher said. “But Dr. Monell has a passion for it.”

So she signed up for the training, and to her surprise, it didn’t take long for the training to become relevant. The first thing she realized was how much it helped her, emotionally, as she went through her day. It helped her examine her own thoughts and actions.

Then she saw how it worked with students. She remembers one time a student didn’t like the way she delivered instructions. Vanscoyk did a quick restorative conference with her, and was struck by how healing it proved.

“So now, instead of just writing them up, I have this process,” she said.

A pretty small incident that in the past could have escalated to suspension became an opportunity for something else.

“It’s created this safe space for students,” she said.

Restorative conferences are an opportunity for students who violated the handbook to sit with an educator trained in restorative practices to process the violation and think about how to move forward productively. If the violation involves an incident with another student or teacher, all parties sit through conferences together and talk about how they made each other feel, acknowledge the harm they caused each other, and come to a resolution with one another.

The school calls parents before restorative conferences to explain what’s happened and what the conference looks like.

“I’ll say, look, this is what the consequence actually is, but instead I can give you this and your child’s going to go through a sort of conference,” Monell said. “And then when I tell them what it is, they’re like, ‘That’s amazing. Go ahead.’”

Sometimes, if the violation is a minor one, parents are given the choice of having their student participate in a conference instead of missing any days of class for RS.

“And it’s really become something parents are receptive to,” Monell said. “They’re seeing how it’s positively impacted the students.”

Pivoting and innovating during COVID

By 2019, the school had trained 40 educators on restorative practices and was seeing disciplinary referrals reduced.

Not only that, but the RS team grew to two people, so while one stayed with students in RS, the other could float to visit the classrooms of kids who just left RS — to help them work on what they’d learned in the usual class setting.

“We were on a great roll,” Monell said.

Then, COVID happened. All of a sudden, urgency demanded attention in a lot of other areas. Monell said she was thankful to have a restorative team already in place. That team shifted from running RS to doing some of the COVID tracking.

One of the things they were tracking were school absences.

“During COVID, the kids were not motivated,” Monell said. “Kids being out of school, they just weren’t interested in coming back. We ran our attendance numbers and looked at the kids who were not coming to school, who were taking care of little brother or little sister.”

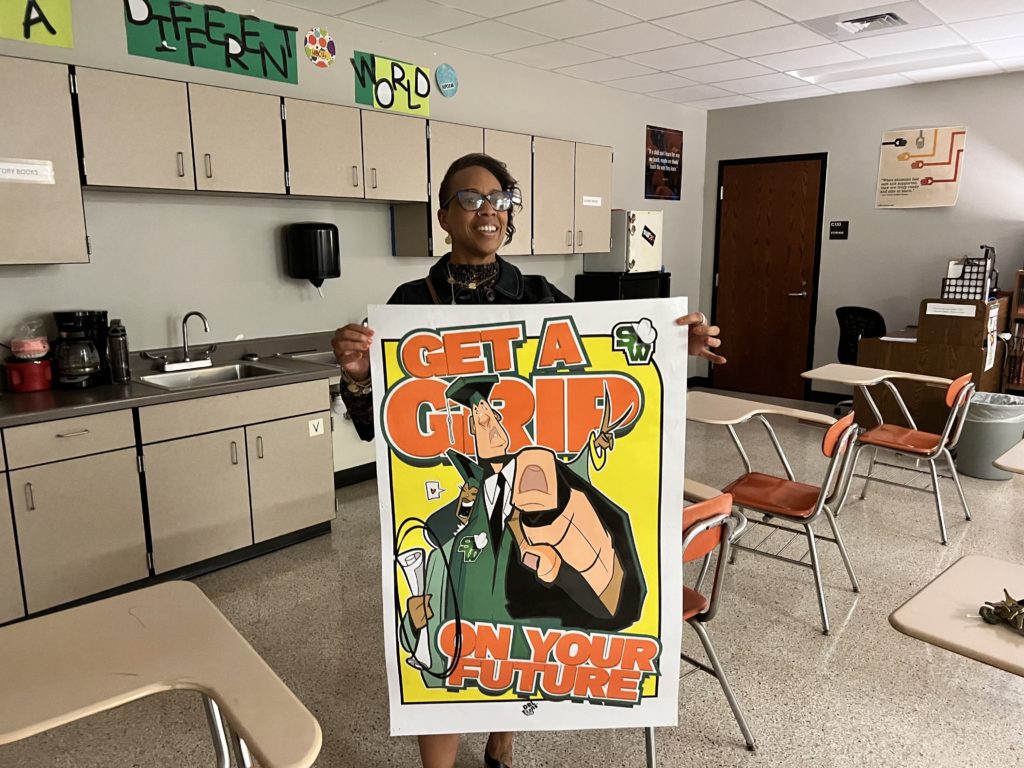

To help these kids, Monell designed a program called “Get a GRIP.” GRIP stands for Group Restorative Intervention Practices.

The school put students with attendance issues through a special program where they talked about how important attendance is on things like grades and graduation — as well as the importance of grades and graduation. The program incentivized students by offering rewards for hitting attendance, class participation, and grade goals.

At its conclusion, Monell said the school saw a 40% increase in attendance, 60% increase in class participation, 60% increase in the amount of completed assignments, and 80% of students improving their grade point average.

When equitable practices work, they’re worth investing in

The restorative practices have been especially helpful for students with learning differences and students of color. Statewide, these subgroups are disciplined more frequently than their peers, and it was true at Southwest Guilford, too.

In fact, when the high school ran its data to identify the students who were most often referred for disciplinary reasons, it found that the top 40 were all Black males. The restorative practices were helping to change things at school, but to focus on this subgroup, Monell started a barbershop program on Wednesdays.

“I have two boys so I know the barbershop is the place you go to talk,” Monell said. “That’s just the place and it’s comfortable.”

So Monell partnered with Gene Blackmon, who started Prestige Barber College in Greensboro with the hope of changing his community “one cut at a time.” Blackmon brings chairs into the school so these kids can sit in the “barbershop” and get their haircut during the lunch period. Monell even orders pizza for them.

Teachers from the school pop in and the kids talk with their teachers and the barbers — engaging in real conversation.

“We just wanted to know what was going on with them, what they were thinking,” Monell said of the students. “So we said, come have lunch, chat, talk about what’s on your mind, because we’re concerned about y’all. I need you in school and not in in-school suspension. So y’all talk it out.”

Monell received a grant recently that will allow her to train about 40 more teachers in restorative practices. But many of the first 40 who were trained have since left the school, so there’s a need to train even more teachers. She’s also down one RS teacher and facing the same hiring strains reported across the state.

There’s also new projects that Monell believes will help further gains made through these restorative programs. These include holding community meetings and having the school improvement team work on making the school handbook more equitable.

It all takes funding, though. More than the school has been able to secure through grants.

“And that’s the thing — even when something is working, you still need to find a way to get the money for it,” she said. “This is really changing lives. Its transforming lives. We have to believe it’s worth investing in that.”