In North Carolina, STEM means more than just science, technology, engineering and math. It means a community of schools, universities, and science centers all across the state.

“STEM education is really preparing kids to think in a different way, to take the whole natural curiosity that they have, to follow a process of inquiry to answer questions,” said Bruce Middleton, executive director of the STEMEast Network. “It’s not just a subject area, it really is a new mode of thinking.”

North Carolina is home to what is called a “stem ecosystem,” a collaborative effort focused initially on eastern North Carolina with support from the NC Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education Center, the NC STEM Learning Network and other STEM organizations and school districts.

What is a STEM ecosystem?

Alfred Mays, program director at the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, describes the NC STEM ecosystem as collaboration between business and industry with the public school system, higher education, community and technical colleges, local municipalities, after school programming and STEM resources like museums.

Mays is responsible for managing grant competitions in science education and diversity of science in North Carolina, in everything from elementary school programs to postdoc research.

The ecosystem began with the NC Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education Center, which acts as a hub for incubating and facilitating STEM education in the state. It is housed by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

“We started to look at how do we create systems that consist of multiple partnerships, multiple organizations, centered around providing education and resources for STEM education,” Mays said. “In that it influences workforce development and everyone has a common mission around that synergy with these different organizations.”

Some of these partnerships include Snowden School in Beaufort County supporting a school robotics team and partnering with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Science Action Clubs being initiated into Boys and Girls Club after-school programs, and teachers participating in sessions that connect real-world needs to actual school curriculum.

On a national scale, North Carolina became one of the first 27 STEM ecosystem models that would receive funding in part because the STEMEast system already in place in 11 contiguous counties in the eastern half of the state, including Beaufort, Cumberland, Greene, Johnston and Wilson counties.

“We were working in 11 school districts, which meant we had at least the collaborative effort going on,” said Middleton. “We had eleven of the major employers in the area, which is another part of that ecosystem. The beginning was already there, the nucleus of collaboration.”

The design was replicated for the western half of North Carolina as STEMWest in early 2016, which partners with eight new local businesses each summer to create project-based learning units focused on a problem in their business.

What does it mean for North Carolina’s students?

“There are more opportunities, and access, to STEM programming, for one,” Mays says.

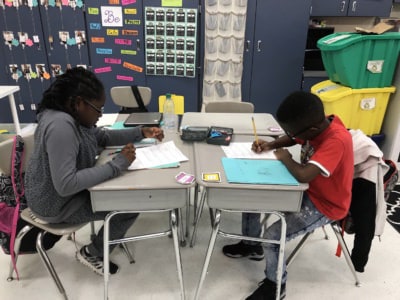

A major part of the STEM ecosystem is fueling the “school to career” pipeline, says Middleton, which traditionally included K-12 education, community colleges, and four-year institutions. STEM education through this ecosystem pushes for independent learning as students are taught to ask questions.

Additionally, some of the first steps of STEMEast were just bringing STEM labs to middle schools along the aerospace corridor. Middleton said that because of labs like the ones in STEMEast, kids are more “career aware” in the both STEM fields and overall. In addition, there has been a positive impact on their test scores.

“We hope that’s because kids are becoming more engaged in school and becoming better thinkers in terms of being able to problem solve,” he said.

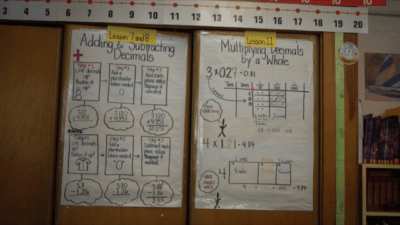

In Greene County schools, STEM is “infused” in all of the curriculum from Pre-K to 12. Greene Central High School met the “Model Level of Achievement” level, the first in the state, for a STEM school by interweaving STEM concepts into classes like Spanish and World History.

“Whether you’re learning about history or British literature, there’s some opportunities to make connections and do some inquiry and hands on work related to that content,” said Frank Creech, chief academic officer of Greene County Schools. “Those are our STEM courses and what delineates them from the standard version of the content.”

Carol Moore, the coordinator of STEM West, developed a system called “Filling the Gap,” which allows teachers to connect with local businesses to create problem-based scenarios for students in science, math and Career Technology Education courses and connecting them to curriculum and STEM related careers.

This past summer, 16 teachers from from Catawba, Alexander, Burke and Lincoln counties worked with companies like Concept Frames, RPM Wood Finishes Group, Inc., SpartaCraft, to develop project-based learning ideas.

“The teachers align what they have to teach in their content with what the businesses say they need,” said Moore.

One of these projects was between an anatomy and physiology class at Bunker Hill High School and a furniture company where they worked on ergonomic recommendations for the company’s seamstresses.

“It’s a type of inquiry where the kids say, ‘I have to do this, what do I have to know to actually do it?’” Moore said. “They have to be able to find all of the information to solve that problem.”

What’s next?

The next step for Mays in growing the STEM ecosystem across North Carolina is finding successful models and programs to scale across a particular region or across the state.

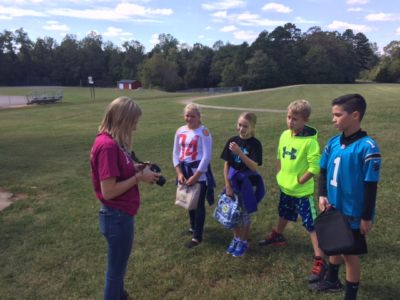

One example of a growing ecosystem model, Mays says, is with the Aurora Fossil Museum, which is partnering with East Carolina University Faculty and the local school systems to help out with housing or even food for summer camps at the museum.

Additionally, Middleton said STEMEast is looking into ways to take field trips virtual so students can receive lessons from experts at museums like the Aurora Fossil Museum or see the inside of the Spirit Air Systems without the hassle of a full field trip.

With funding from the Duke Energy Foundation and the Appalachian Rural Commission, Moore has began to set up 26 “GEMS”, or Girls Excelling in Math and Science, clubs at elementary and middle schools in STEMWest.

Now, Moore is looking for sustainable funding and support from the legislature to continue to bring STEM programs to the western part of the state.

“The umbrella over all of us is that we are really trying to provide that workforce that we know our region already needs because of current jobs can’t be filled, but also to attract new industry into the area because we have a STEM workforce that is ready to engage with those types of skills that the new industries are looking for,” Middleton said.