Recently, I had the opportunity to visit with Rusty Hall of Old Town Elementary in Winston-Salem again. Last year, my colleague Katy Clune and I visited his school. It is a Title 1 school, meaning that over 40 percent of students at Old Town face poverty. In addition, over 70 percent of the students are ESL (English as a Second Language) students.

When we visited with Hall, Clune reminded us, “A population like ours gives us a constant emotional pull. Teachers can burn out.”

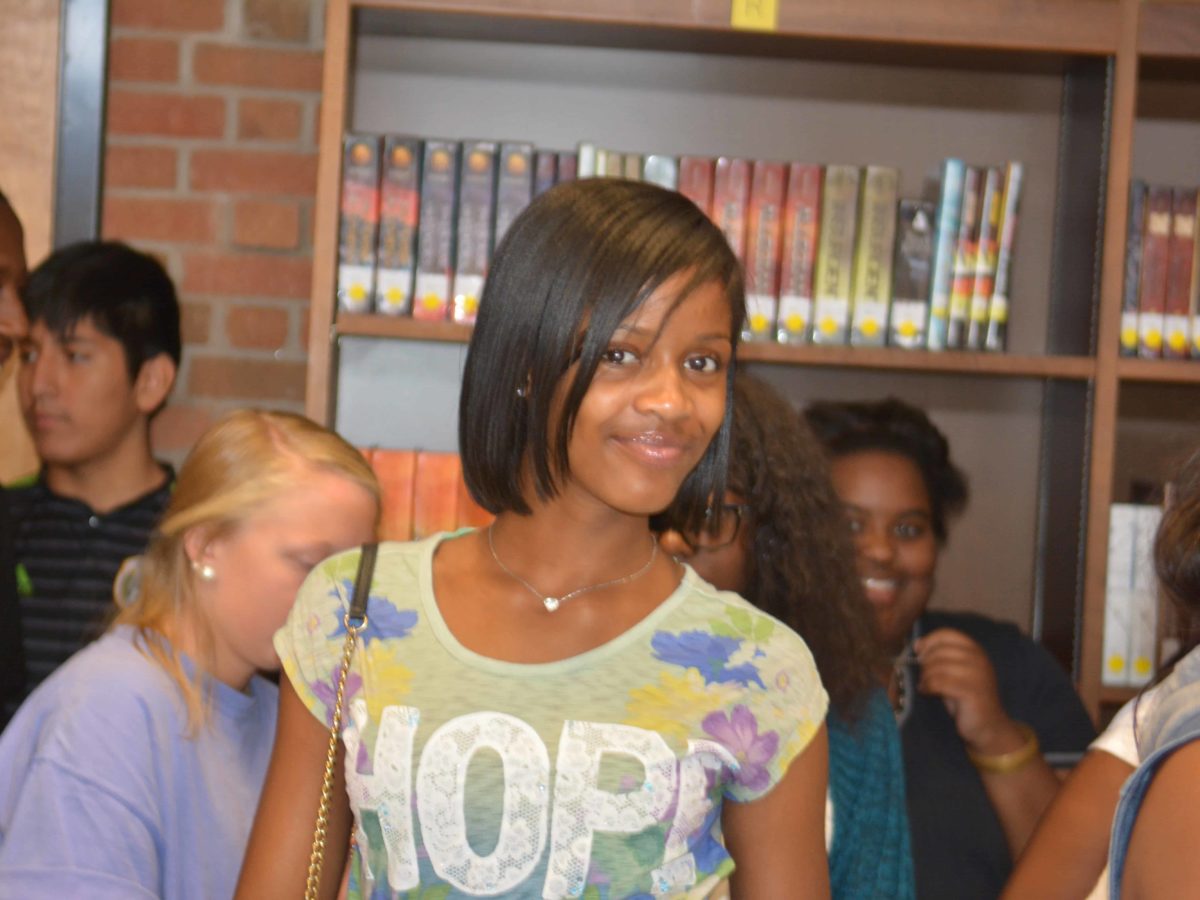

Yet we saw signs of hope and possibility everywhere.

Test scores were beginning to rise, the walls were decorated with beautiful drawings from creative students, and the energy was palpable.

At a Gathering for Good in Winston-Salem hosted by the Jamie Kirk Hahn Foundation, Hall spoke of hope as a metric of success — derivative of other measures of success. He told us, “When I arrived, I would estimate that more than 80 percent of our students listed their career goals as being a professional athlete or musician. Today, that number is flipped, and the overwhelming majority list astronaut, or doctor, or lawyer, or other professions.”

Hall went on to say that hope was a metric of success for him.

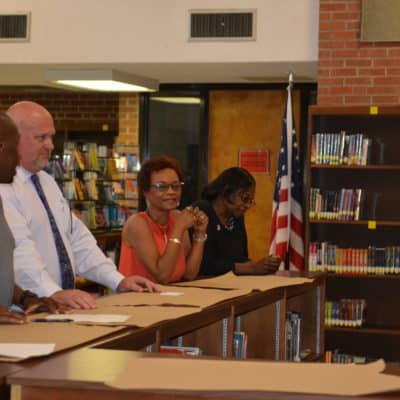

Later that same week, EdNC traveled to Edgecombe County to host a Public Policy Boot Camp for students and educators. And, happily, we can say that policymakers, community leaders, principals, teachers, and parents joined us as well.

To place Edgecombe in context, more than 38.1 percent of children in Edgecombe County live below the poverty line. And more than 80 percent of the children were eligible for free and reduced-price lunch prior to the Community Eligibility Provision, which now allows 100 percent of the children to be served.

We have spent a lot of time in Edgecombe County for the same reason that we have traveled to Old Town Elementary and Hoke County. We see signs of hope, possibility, resilience, and turnaround there too.

One of the more poignant moments came when one participant in boot camp spoke up and said, “It matters how you talk, but also how you listen.”

We heard from others that Superintendent John Farrelly’s work to “saturate the community with possibility” was beginning to take hold.

Our conversation around measures of success grew particularly heated when a local administrator declared that the state’s measurement of success — which relies on a formula based off of 80 percent achievement, 20 percent growth — bothered him. The administrator went on to say that the letter grades should be driven by growth, illustrating that Edgecombe’s Patillo Middle School, which would have received an A if the formula was 100 percent growth, was far lower due to the emphasis on achievement.

“Letter grades boil down the complexity of education,” lamented the administrator.

An educator in the room responded by saying, “My class is a hands on class, and it is boiled down to 100 multiple choice answers on a test.”

The educator offered up one solution: The test ought to match what the student needs to know when they leave each individual class.

Both the visit to Winston-Salem and Edgecombe offered up a different vision of success for those of us who think about how to connect what happens in the classroom with public policy. And this vision is informed by those who do the work on the ground in our schools every day.

Educators, parents, administrators, and students all echoed the same theme — our children are not a monolith, neither are our schools, and it is long past time that we begin to examine how we might honor their individualism in how we assess whether our teachers and schools are working. This was echoed on EdNC’s recent trip to Singapore.

We need more holistic ways to think about student, teacher, and school success.

It is time for all of us to listen.

Recommended reading