With the former head of a Holly Springs charter school questioning its rapid growth, charter schools are in the news again. In North Carolina, charters are debated often — most recently at a Public Schools First NC event, where school board members, teachers, and policy experts convened for a half-day event called “Impact of Privatizing Public Schools: A Crisis in the Making.”

Speakers across three panels at the Oct. 12 event talked about issues involving state charter schools and voucher programs, presenting data to discuss charter schools’ accountability, their failure to outperform traditional public schools, and their potential segregating effects on public schools.

The Q&A sessions sometimes got tense. And when speakers brought up segregation, at least two audience members could be heard referring to the “race card.” But discomfort is not a reason to avoid these conversations, one speaker said.

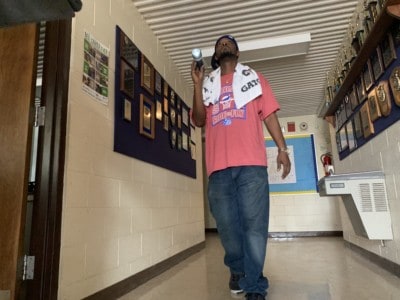

“We just need to feel uncomfortable about where we are with public education,” said Malisahi “Shai” Woodbury, the first African-American chair of the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Board of Education, “so that we understand the urgency of acting and doing something better.”

That urgency, speakers on each panel said, is grounded in reversing a trend toward resegregation of public schools — which they said is attributable to voucher programs and the boom in state charter schools over the past eight years.

What are charter schools? Charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately operated, were first allowed in North Carolina in 1996 — capped at 100 schools. Since 2011, when the cap was lifted, the number of charters has steadily grown. Almost 200 are operating now.

What are vouchers? In 2013, North Carolina created the Opportunity Scholarship Program, which provides vouchers for students to attend private schools. In 2016, the legislature expanded the program and established an Opportunity Scholarship reserve fund to be augmented by $10 million every year until 2027-28, when it will plateau at $144.8 million in annual funding. Last year, $37.9 million of the allocated $45 million was awarded. Even though the allocation wasn’t exhausted, it will increase next year to $55 million.

Stu Egan, a teacher in the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools and the author of Caffeinated Rage, presented DPI data from 2017-18, when the state had 173 charter schools. Egan said these data go to the heart of diversity issues — racial and socioeconomic — among charter schools. For instance, according to his slides:

- One hundred and fifty of the 173 charter schools had a student population that was at least 50% one racial/ethnic group.

- More than 110 had a student population that was at least 65% one racial/ethnic group.

- More than 50 had a student population that was at least 80% one racial/ethnic group.

- One hundred and thirty two charters had a student population that was less than 40% economically disadvantaged.

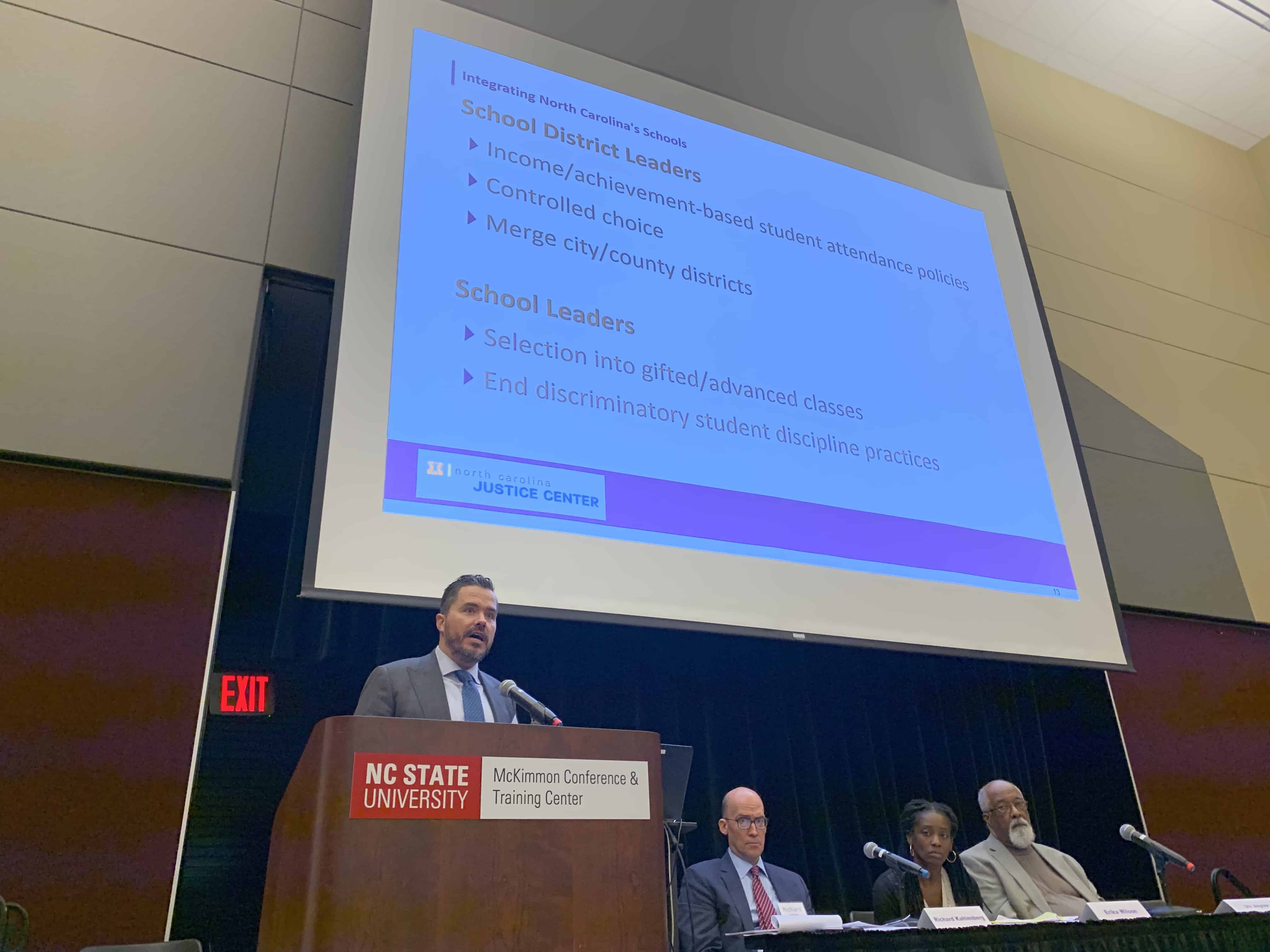

Kris Nordstrom, senior policy analyst for the North Carolina Justice Center’s Education & Law Project, pointed to data (primarily from his Stymied by Segregation report) showing an increase in traditional public schools that were racially and/or economically isolated. Racially isolated schools, for purposes of the statistics, were those that had at least 75% students of color; economically isolated schools were those where at least 75% of students received free or reduced-price lunch.

From 2006-07 to 2016-17, every category increased:

- Racially isolated schools increased from 19% to 24%.

- Economically isolated schools increased from 21% to 37%.

- Racially and economically isolated schools increased from 13% to 19%.

Tying those increases to the effects of charters, Nordstrom pointed to data showing that in 72% of counties with at least one charter school, the charter schools increased the county’s dissimilarity index (with charter schools skewing whiter than their district).

Woodbury read from a paper she co-authored with Edwin Bell, a scholar and professor of educator preparation, saying that charters offer choice to parents, encourage parental engagement, and can transform public education.

“Ideally,” she said, “it is a good thing. However, the benefits of this good thing, intended for every student, have become progressive for only some children.”

One reason, she and other panelists said, is so-called “white flight,” which refers to use of charters and voucher programs as a way for wealthier and white families to flee an increasingly diverse public school system — moving into schools that arguably are less accountable and can exclude students based on a number of factors.

Carol Sawyer, a member of the Charlotte-Mecklenberg Schools Board of Education, says her district has seen overt examples of this.

“Charlotte-Mecklenburg has a long history of tension over community integration,” she said. The school district is roughly 30% white, 30% Hispanic, and 40% African-American, she said, but its distribution is mostly African-American in the city of Charlotte, while six surrounding towns are “both whiter and more affluent than the rest of the county.”

“There have been many efforts over time for the towns to secede from CMS,” she said, citing use of charter schools as the latest example.

She said that in 2007, the town of Huntersville did a study on seceding from CMS. The research revealed a local tax impact of $1.24 per $100, which would be an increase from 30.5 cents. As an alternative, the town looked into starting municipal charter schools — which would prioritize admission for residents, who are mostly white and affluent.

“[It’s] under the pretense that [the district] was too big,” Sawyer said, “But they are generally veiled covers for, ‘We want our kids to go to our schools and not have to mix with other kids from other parts of town.'”

But the legislation governing charter schools in North Carolina has requirements, and one is that an entity cannot take on debt to fund a charter school. This would force towns to again look at raising taxes. For now, the towns of Huntersville and Matthews have not pushed forward with municipal charters.

“The threat of municipal charters is actually what the towns are using mostly to try and intimidate Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools” in student assignment decisions, Sawyer said.

While some panelists felt they were “preaching to the choir,” a small, vocal group of charter school advocates asked questions and said they were made to feel like the enemy.

“I’ve had parents from all over the district who have contacted me about school choice and about being given a hard time about leaving the district,” said A.P. Dillon, who is a freelance journalist and blogs as Lady Liberty, but attended as a parent and school choice proponent. “And the main thing they were getting push-back on was, if they were a white family, they were being labeled as a segregationist or a resegregationist. You know, this horrible casting of school choice families leaving the district being the same as going back to Jim Crow.”

Dillon said that if parents do not think their child is getting a “sound basic education,” echoing words in the state’s Constitution, they should feel empowered to make a different choice without getting a negative label.

“Parents choosing to associate with another entity for their child and their child’s best interest — that’s not segregation,” she said. “That’s freedom of association, whether or not they happen to be white or black. It’s the parent actively advocating for their child’s education.”

During time allotted for audience questions, Dillon noted the wait list for charter schools.

Christine Kushner, a policy analyst and member of the Wake County Board of Education since 2011, offered an introspective response: As school choice increases, public schools “have to work harder to become the first choice.”

Regardless of the reasons parents choose charter schools, the data demonstrated a growing concentration of one racial or ethnic group in schools. Speaker Richard Kahlenberg, director of K-12 equity and senior fellow at The Century Foundation, argued that the public good is best served by integrating schools — both along racial and socioeconomic lines.

“All students benefit from being in diverse classrooms,” he said. “Middle class students benefit, African-American students benefit, white students benefit, low-income students benefit — all students benefit from having a variety of students from different backgrounds and different life experiences.”

Kahlenberg said that research shows that different life experiences lead to deeper educational experiences in classrooms, and that problem-solving becomes more creative when issues are approached by a diversity of students.

These benefits, he said, carry forward to the job force.

“We know that there are harms associated with concentrated poverty,” he said. He talked about a study that showed the most important factor driving student achievement being the socioeconomic status of the family. The next most important predictor was the socioeconomic status and diversity of peers in that student’s classroom.

Kahlenberg cited a Stanford study that looked at 50 million students and 350 million test scores. The study concluded that there was not a single example of a school district with minority students disproportionately attending high schools where there was not a large racial achievement gap.

“If it were possible to create equal educational opportunity under conditions of segregation and economic inequality, some community among the thousands of districts in the country would have done so,” he said. “None have. Separate is still unequal.”