This week is National School Choice Week, so I thought this would be a good time to check in on the state of school choice in North Carolina.

First off, when we talk about school choice, we’re not really talking about one thing. Instead, the term is an umbrella for a multitude of things that give students and their families the option of where they want to go to school.

EdNC’s Mebane Rash writes of her trip to Singapore, one of the leading educational systems internationally, “With a system of education that is focused on all students comes a focus on fit, as we see in our own state. Parents want a school and an educational experience that is the right fit for their child.”

One of our options, and the option that serves the most students in North Carolina, is traditional public schools, and in her speeches Mebane often reminds people that our traditional public schools offer an abundance of choice — magnet choice, year round choice, early college choice, choice for alternative students, and more.

But most often when school choice is being talked about, three things are being discussed: charter schools, the opportunity scholarship program (both the basic program and the one aimed at students with disabilities), and the Education Savings Account.

Let’s run through them one by one.

Charter schools

Charters are considered public schools, but they are free from oversight and interference from the district in which they live. They are granted certain exemptions from the requirements applied to traditional public schools — things like curriculum, finances, teacher certification, calendars, and more. They can be operated by all sorts of people, organizations, or institutions, including for-profit or non-profit charter management or education management organizations.

Here is an overview Mebane wrote on the 20th anniversary of the charter school legislation in North Carolina.

Charter schools are answerable to the state’s Charter School Advisory Board, which makes recommendations to the State Board of Education on who can open, who should close, and whether schools get renewals or not.

According to the latest annual charter school report, the state has 184 charter schools right now (two of which are virtual charters), with 22 in the process of opening. The state received 35 charter applications last year.

Once upon a time, the number of charter schools that could exist in North Carolina was capped at 100. But in 2011, the Republican-led General Assembly lifted the cap, which allowed more charters to open across North Carolina. It is important to note, however, that charter schools are still more prevalent in urban parts of the state and there are many counties that still don’t even have one.

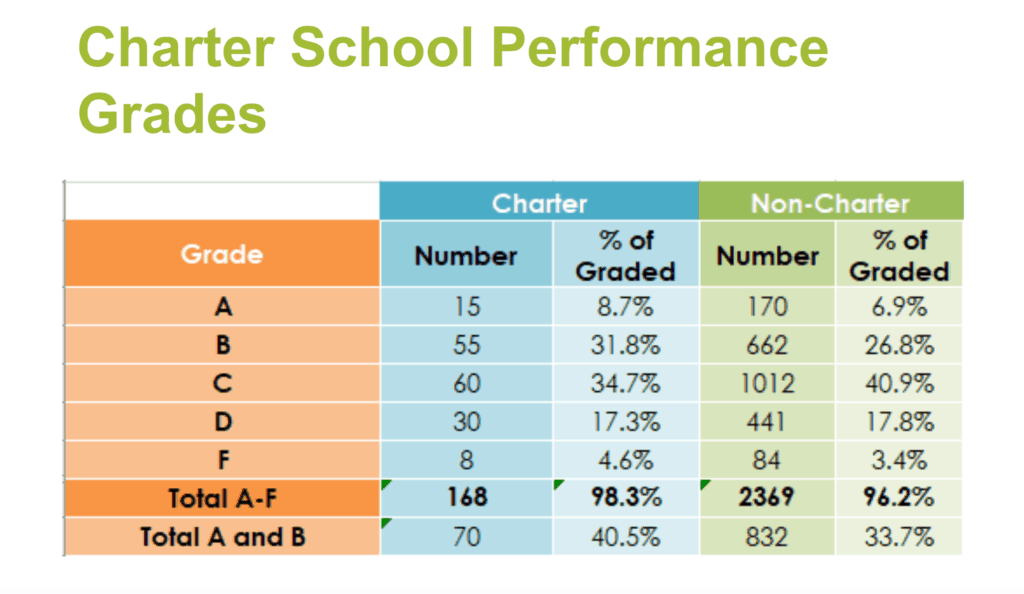

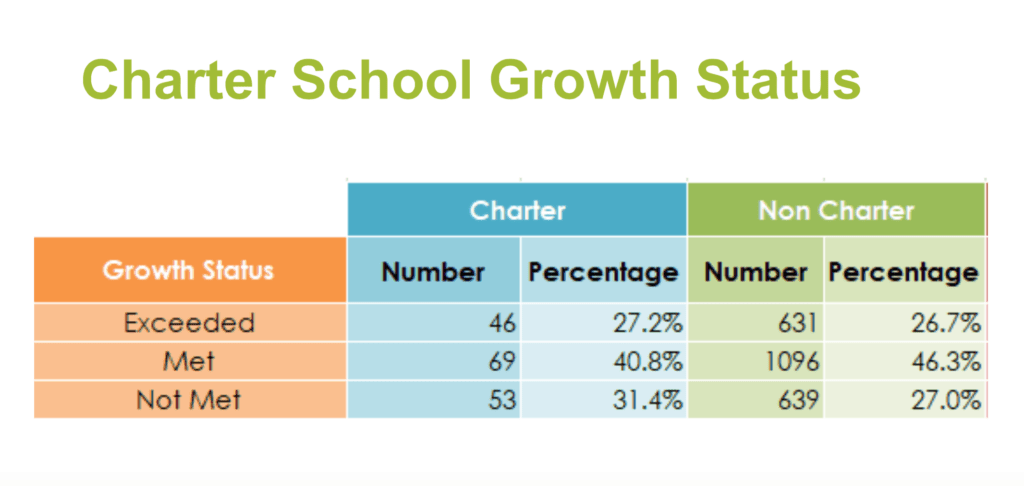

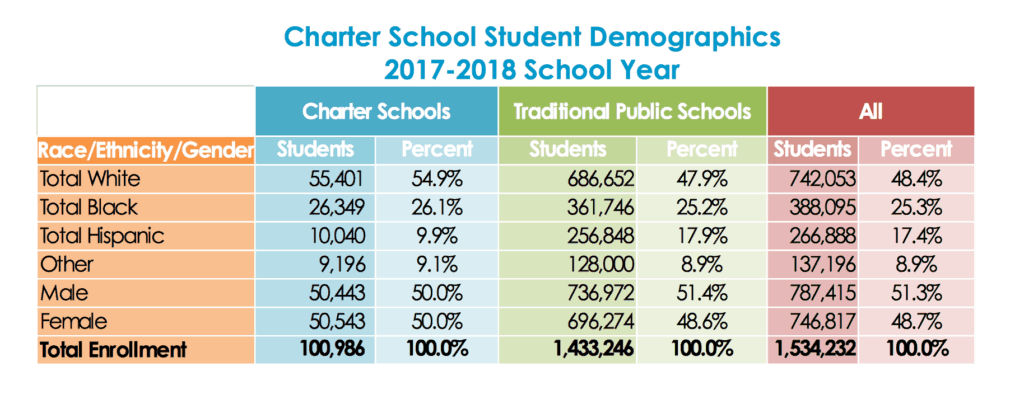

Here is how charters are faring both in terms of performance and demographics.

Charter schools have a long history in North Carolina and originally came into being when Democrats were in control of the state. It is only fairly recently that the subject seems to be more and more divided along partisan lines, especially in places where the market share of students served by charter schools impacts traditional public schools.

Charter schools are funded by the state, but they receive a different amount of funding because charters don’t get state (or local) dollars for facilities, transportation, or food. Proponents of charters say they offer options for students who may not be a good fit or may be served poorly in a traditional public school. The intention behind charters when they began was that they would serve as laboratories of innovation that could then be modeled in traditional public schools. Some still say that motivation is alive, while others say it has long been abandoned.

An added controversial element occurred when legislation passed in last year’s short session that will allow four towns in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district to open and operate their own charter schools. House Bill 514 enables the towns of Matthews, Mint Hill, Cornelius, and Huntersville to open charters that favor their own populations, if they so choose.

That bill did not have a provision that would allow teachers at these potential town charter schools to opt into the state’s health and retirement plans, which could disincentive teachers from joining the schools. That provision, however, was put into a technical corrections bill that passed the General Assembly in December, clearing the last hurdle for these town charter schools.

The argument against these towns opening their own charter schools largely revolves around the possibility that it will lead to re-segregation in the area, though supporters say it’s simply a way for the towns to more adequately educate a population that isn’t being served well by CMS schools.

Here are some questions the policy researchers at EdNC continue to ask about charter schools in North Carolina:

- What are best practices from charters over the past two decades, and how do we scale them?

- What innovations in practice and management are needed and how do we incent them?

- Who is responsible for sharing information about best practices with public school administrators and educators, parents and policymakers? If charter principals were expected to serve that function, they have a school to run. If not them, then who?

- Have we done a good job of enabling charters and districts to work together? Has that been done elsewhere? If so, how do we replicate that across the state?

- How prepared are we as a state for the continued rise in percentages of rural students attending charters?

- As the number of charters continue to grow as a percentage of market share, what changes on the horizon might we be able to plan for and anticipate using the examples of places like Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and New Orleans as guides?

- Our state has never clearly identified our expectations for charter school performance. How good is good enough?

- What questions do you think we should be asking about North Carolina’s charter school experience? Who has a story to tell that has not been told?

Opportunity scholarships

Opportunity scholarships, often called vouchers, give low-income students the option of receiving a $4,200 scholarship to attend a private school of their choice.

The General Assembly added $10 million-increases to the base budget of the state for every year leading up to the 2028-29 school year. Last year, the state had budgeted about $44 million for the program, which equates to between 8,000 and 8,300 scholarships. In the 2028-29 school year, the funding will be up to $145 million. It will continue at that rate every year thereafter. That equates to about 36,000 students being able to take advantage of the program.

The disability opportunity scholarship program is similar, but it applies only to students with disabilities.

A tweak in a technical corrections bill just before Christmas allows students already in private school to access the disabilities grant as long as they were in a public school the previous year.

Education Savings Accounts

The Education Savings Accounts is the newest school choice program. It gives up to $9,000 in public money to families of children with disabilities to use on tuition for non-public schools, books, other supplies, and testing costs.

As I mentioned, school choice in North Carolina is becoming more partisan and controversial. The opportunity scholarship program, in particular, is seen as a way to siphon students out of the public school system into private schools that lack government accountability. Particularly controversial is the fact that opportunity scholarships can be used for students to attend institutions that heavily favor religion in their curriculum.

In the upcoming long session of the General Assembly, education policy thinkers don’t anticipate there being a whole lot of changes in any of these programs, though there may be discussion.

This is the lay of the land when it comes to school choice in North Carolina. There is endless debate about the effectiveness of these alternative choices, the motivations behind offering them, and the long-term consequences to the traditional public schools from these other options. But the fact remains that they exist.

This week, EducationNC will be reporting on school choice week events. Stay tuned to our coverage as the week unfolds.

State Board of Community Colleges

The State Board of Community Colleges last week approved $554,046 to go to Wake Technical Community College (WTCC) for the Finish First tool. This is a tool developed by Wake Tech that uses an automated process to check student transcripts to see if they are missing credentials that may help them complete their degree. The goal was to develop an easy way to show students that, in some case, they may be short of a degree by only a few classes or even be eligible for a degree they didn’t know about. The college hopes to entice students to finish by showing them how close they are to completion and the steps they need to take to get there.

“This is a really important one,” said system president Peter Hans.

The funding comes via a grant from the John M Belk Endowment. An additional $200,000 will go to Wake Tech through a Lumina Foundation grant, which will help the college continue to develop the tool.

Wake Tech has successfully used the tool at 11 colleges. The tool has thus far identified more than 30,000 students who are already eligible for a degree or are only a few credits short at Wake Tech. The goal is to eventually ramp up the tool so that it can be utilized at community colleges across the system.

The State Board also approved a series of legislative priorities that it will be sharing in common with the University of North Carolina System.

“This is something the system has not done before,” said Mary Shuping, director of government relations for the system.

One of the priorities includes transfer student scholarships, which will be used to incentive community college students to finish their degree before transferring to a four-year institution.

Shuping said this is important because less than one-third of community college students actually finish their degrees before transferring.

“But if they do, they do better, sometimes better than the native students,” she said. “…we hope to keep those students with us to get that associates degree.”

The list of priorities include:

1. Summer scholarships for UNC and NCCCS students

2. Transfer student scholarships

3. Improve credit transfer for community college and military-affiliated students

4. Expand the availability of Open Educational Resources (OER)

Read details about the priorities here.

The State Board also voted to make Lisa Chapman, the system’s senior vice president/chief academic officer for the North Carolina Community College System, the president of Central Carolina Community College.

Editor’s Note: The John M Belk Endowment is a funder of EducationNC