A series profiling individuals working to creatively raise up North Carolina’s education system.

A series profiling individuals working to creatively raise up North Carolina’s education system.

At Old Town Elementary School in Winston-Salem, hip hop music plays in the halls before classes begin. The walls are lined with student art projects — from colorful, Mexican folk-art inspired birds to smiling student self-portraits.

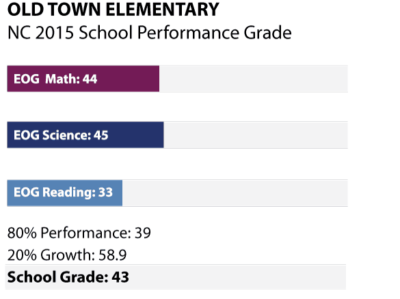

According to Principal Benjamin “Rusty” Hall, “We have great kids. Very low discipline issues, they are eager to learn and are a good group.” Last October, the Winston-Salem Forsyth County School district named Hall the Principal of the Year. And yet — according to the official North Carolina public school assessments — Old Town Elementary received a D (43) on its 2014 and 2015 report cards. Every public school in North Carolina is issued one of these performance grades, which reflect 80 percent achievement and 20 percent growth in student reading, science, and math test scores.

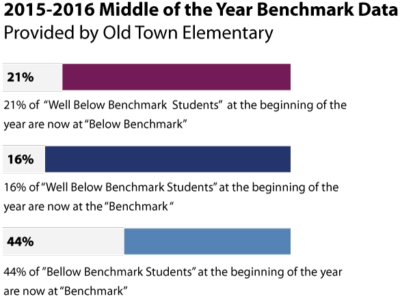

However, thanks to Hall’s innovative leadership, Old Town is in the midst of a transformation. The school is enjoying higher levels of student achievement, parent engagement, and satisfaction — despite the school’s “failing” grade.

“The [school performance grades] don’t account for nuances. There’s got to be a better system. This system is not set up for challenging populations. I think it is imperative that we treat all schools as we treat our kids: as individuals. ”

— Rusty Hall

Since he was a senior in high school, Hall knew he wanted to teach. In need of a few more credits to graduate, he signed up for a mentoring program with elementary students on a whim. “I just fell in love with it,” he explains. “I said this is what I want to do.” He majored in elementary education at UNC-Wilmington and earned a master’s degree in school administration at Gardner–Webb University in Boiling Springs. After starting his career in public education as a middle school math teacher and football coach, he was promoted to high school assistant principal in nearby Stokes County. In 2012, he took the position of principal of Old Town Elementary. “When [this job at] Old Town came open, I knew that’s where I wanted to be,” says Hall.1

Hear Hall on why he loves education:

Clockwise, from top left: Hall let his students turn him into a “human Rice Krispy” treat after they met learning goals; In the teacher conference room at Old Town, every single student’s progress is charted on the wall; Hall’s “Wall of Fame” at Old Town.

Hall considers being a principal a form of service to his community. “I don’t feel that this is a job as much as it is a way to serve kids that are in need, whether [the need] is social, emotional, or academic,” he says. Hall’s father is a preacher and his mother is a retired teacher. He was raised in a small community in rural Granville County, and says “from day one” he felt his parent’s “sense of service” and saw how an individual can positively impact their community.

At Old Town, Hall and his team are positioned to serve a community in great need. The elementary is a Title 1 school, which means over forty percent of students come from families confronting poverty. Most of the 650 students at Old Town are Hispanic, with a majority of families heralding from Mexico.

“A population like ours gives us a constant emotional pull. Teachers can burn out.” — Rusty Hall

“This is very much a working poor community,” explains Hall. “Parents are working several jobs, some of their legal status is unknown… There are ups and downs for a lot of our families.” Hall keeps his focus on serving his students, but he knows life at home can impact classroom success. Some of his students eat their only meals for the day at Old Town, and parents can struggle to help with homework assignments. Facing challenges which span the “emotional, social, and academic,” Hall has initiated a new teaching and staff development model at Old Town that proactively accounts for this context.

Principal Hall works hard, intellectually and physically — he’s let students turn him into a human Rice Krispy treat and duck-tape him to the wall after achieving learning goals. If Old Town meets his current reading challenge, Hall vows he’ll camp out on the school’s roof for a night. It’s this infectious willingness to take risks and put himself on the line that has contributed to Hall’s success in instigating a new model at Old Town — and look past his school’s “failing” grade.

Hall is also a strong believer in nurturing professional development and career goals in his teachers. “I believe in [professional development] so much, I built it into my Title 1 school budget,” he explains. Everything Hall has achieved at Old Town, he has initiated with the support of his staff.

“Everything we’ve done at Old Town has been a team effort. I truly believe that if you plant the seeds like a garden, it will grow.”

— Rusty Hall

Hall and his teachers have creative ways to motivate students to read at Old Town. These “Caught you reading!” cards are handed out students who can use them to “buy” books. A chain of student and teacher “book reports” nearly wraps around Old Town’s hallways.

Hear Hall on embarking on a new model for Old Town:

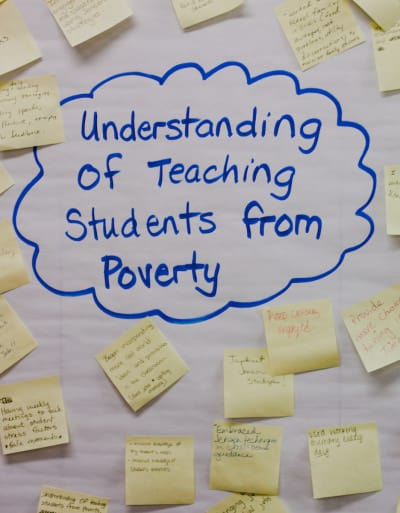

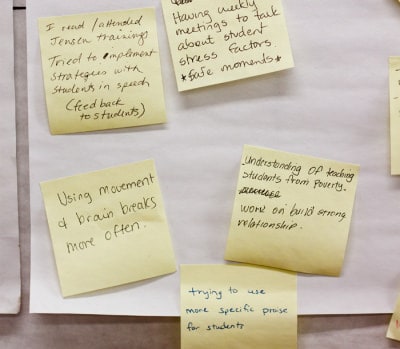

In 2014, a generous private donor approached Hall and asked him what he could do to change Old Town given the funding. Reflecting on this offer, Hall thought “we have a good toolbox for reading, we have a good toolbox for math, we just don’t have toolbox for poverty.” Hall proposed Old Town connect with Eric Jensen, former teacher, educational neuroscientist, and author of Teaching With Poverty in Mind: What Being Poor Does to Kids’ Brains and What Schools Can Do About It. Hall instigated book study groups with his teachers, and invited guest speakers on Jensen’s teaching philosophy. His idea: to adopt a new school philosophy in one year.

“I was honest with [my teachers], I said it’s going to be tough work. It’s going to be a lot of hours, a lot of training. I said, ‘I need you to come in with an open mindset that you can do this.’” Staff response was overwhelmingly positive: “The only day I could get Eric Jenson was on a Saturday. Valentine’s Day Saturday. Everybody in this building showed up.”

Now more than a year into this undertaking, Hall and the teachers at Old Town have customized Jensen’s recommendations into a model that is uniquely suited to their students and teachers. “This was a movement, not just something else to do,” Hall explains.

Teachers are now divided into four committees that represent the core values of Old Town: student achievement, mindset, relationships, and culture/climate. “We decided to get rid of all the committees and meetings that most schools have. Everything we do has to fall under one of those four areas.” Staff meetings are completely teacher run, and each committee is co-chaired by two “teacher leaders.” This collaborative model has allowed staff to stay motivated, focused on larger objectives, and to serve as resources for one another.

“With the staff’s mindset, they’re working on creating and doing different things that they’re coming up with themselves.”

— Rusty Hall

Old Town has instigated daily hour-long “intervention” periods where students break into small groups with instructors and work on targeted learning goals. The school also has a bilingual program which begins with one Spanish-only kindergarten class.

From this strong foundation, teachers are implementing recommendations from the “teaching with poverty in mind” model. For one, physical “brain breaks” and daily learning targets help keep students focused. “I have one teacher who says, before every lesson, ‘Shoot your bow and arrow at the target!’ And you’ve got a classroom full of kids shooting an invisibly bow and arrow at their learning target,” chuckles Hall. To meet individual student needs, Old Town has also instigated a daily hour-long block of intervention and enrichment that allows for small-group instruction targeting student needs.

Ms. Rodriguez, Old Town Elementary Teacher of the Year (2015-2016). Small groups and daily reminders about mindset and learning goals are a success at Old Town.

Old Town Elementary Successes2

Parent and community data

- 90% of parents graded Old Town an A or B.

- 94% of parents graded teachers at Old Town an A or B.

- Parents reported that, on average, students spent 22 minutes each night reading, up from 10 minutes last year.

- 97% of respondents reported that their questions/concerns were addressed in a timely manner, an increase of 3% from last year.

- 98% of respondents felt the services of Old Town’s Family Engagement Coordinator were beneficial.

- 96% of respondents said their students grew academically this year, a 4% increase from last year.

Staff data

- Overall, 93% of staff who completed the survey felt that Old Town was a good place to work.

- 88% of the staff felt the professional development on poverty had a positive effect on students.

- 90% of staff surveyed are looking forward to continuing to learn strategies to combat poverty.

- 83% of the staff feel Old Town has a shared mission and goals.

“I know it’s meant as a compliment but when people come to visit the school they always leave with saying ‘This isn’t what I expected Old Town to be like. It’s warm, it’s inviting!’ I want to get away from that. I want folks to expect great things to be going on here — because they are.”

— Rusty Hall

The successes at Old Town don’t stop outside of the classroom. Hall and his team have started a “parent university” with sessions on understanding report cards, how to help with homework, and even financial planning (taught by volunteers from the MBA program at Wake Forest University). His first bilingual class will graduate next year — this model starts with students in a Spanish-only kindergarten classroom. The positive energy shared by staff empowers the school to make the most of community partnerships, too. For example, local church groups organize backpacks of food to send home on the weekend.

Yet all of these successes are not reflected in the state-sanctioned data on Old Town — and this makes Hall worry. He wants to attract the best teachers to his school and grow his student population. A failing grade — with no asterisks, no accounting for poverty, the “summer slide,” or for English-as-a-second language — overlooks the strides forward occurring at this school. Despite its “D” grade, much of what happens inside of Old Town’s classrooms and administrative offices is exemplary.

Takeaways: Words by Rusty Hall

Q: What is the value of thinking beyond North Carolina’s school grade system?

I think we want to use labels to support, not to hurt our schools. We want to attract highly qualified, good teachers. We want to attract students to come to Old Town. I know once they enter my building that they will want to be here. But getting them in the building is sometimes difficult because of those labels. I think it is imperative that we treat all schools as we treat our kids: as individuals. Each school has a set of strengths and a set of areas they can improve on. No two low-performing schools are [alike]. They all have their challenges.

Q: What keeps you up at night?

The social, physical, emotional needs of our kids. The fact that they live in varying degrees of poverty and situationally it can get worse, and it can get better. Knowing we can provide breakfast and lunch for all of our kids, but what happens on breaks when they don’t have that? We have the [food] backpack program that helps them on the weekends, but how can we support our families to help them get out of poverty? It’s a vicious cycle. It’s holding our kids back. I feel a responsibility being a leader in this community to help the community get out of poverty… I think most principals would agree it’s not a job you sleep a whole lot with–your mind is always racing.

Q: What lessons can you share?

Understanding what your data is really telling you, whether it’s good data and you’re cheering or it’s bad data and you get that pit in your stomach. Really dive down and see what is it telling you. Be open to finding the right solution, whatever it is.

The second biggest lesson I’ve learned is teachers are so valuable in leadership roles. Bottom-up tends to lead to more success than top-down.

Lastly, you have to take risks. You may fall on your face, it may not work. Admit when it doesn’t work and try again. I think those three things have really gotten us to where we are.

Resources

Curious about the “teaching with poverty in mind” model? Start here.

Curious about the “teaching with poverty in mind” model? Start here.

- Eric Jensen, Teaching With Poverty in Mind: What Being Poor Does to Kids’ Brains and What Schools Can Do About It (Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2009)

- Workshops and more at Jensen Learning: Practical Teaching with the Brain in Mind

- LeAnn Nickelsen, Maximize Learning NC

- Follow Principal Rusty Hall and Old Town Elementary on Twitter