When North Rowan Elementary was built, there were no interior walls separating the classrooms. It would be considered outdated today, perhaps primitive. Still, what Meredith Williams remembers about her time as a student there is the field trip to the post office and the lessons about how what they were learning connected to the real world.

Over the years, the walls came up. Not just literally at North Rowan Elementary, but figuratively across all schools — where students became a little more isolated in their classes from the outside world and teachers were incentivized to teach for improved test scores rather than real-world learning.

“The reason there’s such an issue, in my opinion, is we have an accountability model that’s on standardized testing,” Rowan-Salisbury Schools (RSS) Superintendent Lynn Moody said. “And we won’t see engagement. You cannot have student engagement if your accountability model is a multiple-choice test.”

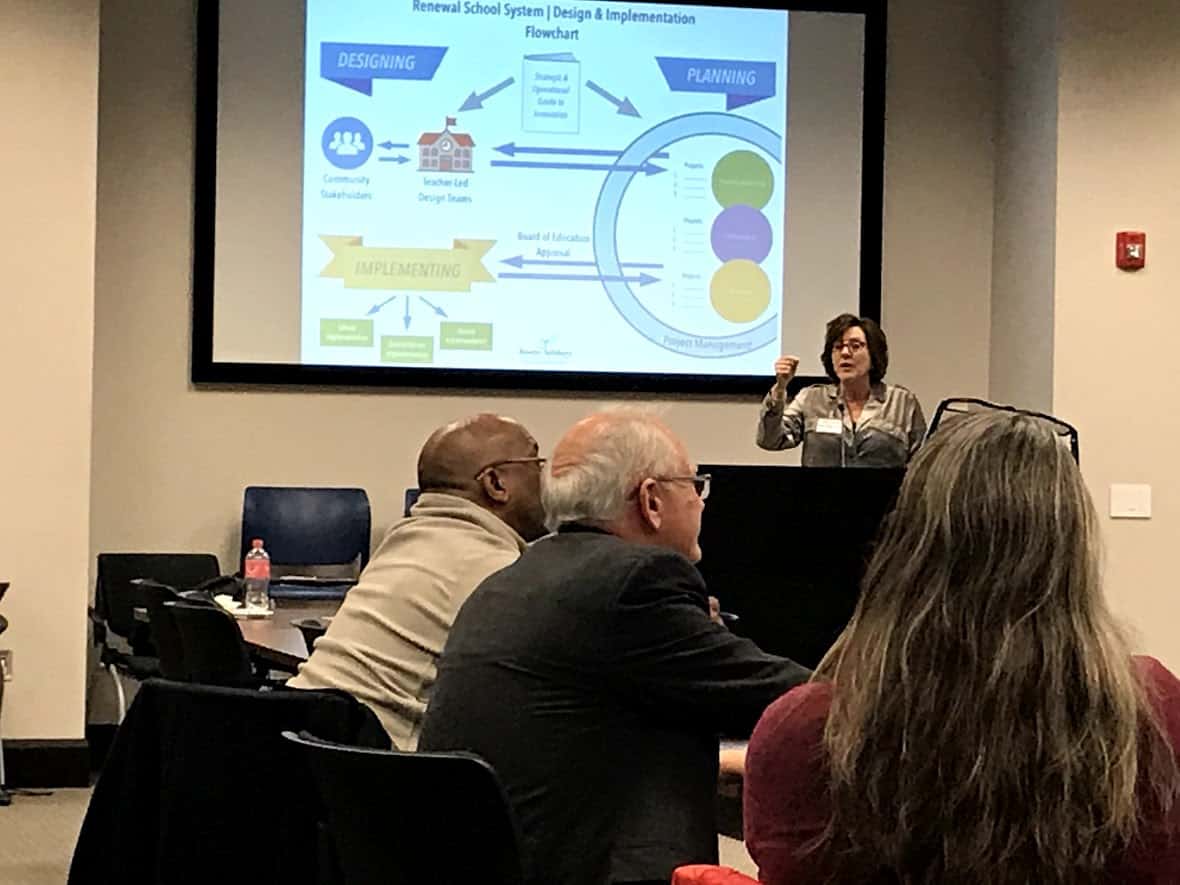

The literal walls will remain, but RSS administrators and teachers are knocking down the barriers between learning in the classrooms and learning for success in the world. The effort began four years ago when the district made a commitment to integrating digital learning in classrooms, and it’s continued to this year as RSS has become a renewal district.

As a renewal district, schools in Rowan-Salisbury have charter school-like flexibility, such as with curriculum, budgeting, personnel, and calendar. Most noticeably, the flexibility allows Moody to empower her schools to operate on a new accountability model.

Test scores at RSS were never especially high. A byproduct, Moody said, of test design and having 66 percent of students in the district living in poverty. Now, teachers are tasked with making sure students are learning and engaged, not simply prepared for standardized exams. After all, she said, testing a student on regurgitation of facts during a three-hour examination is not a reliable indicator of whether a third-grader is reading on a third-grade level.

So her schools are using a different metric to measure student success.

In math, for instance, lessons are based in finance — preparing students to buy a car and calculate payments, count back change, or balance a check book. To measure reading at, say, a tenth-grade level, students should be able to read a minimum number of tenth-grade level books and demonstrate an understanding of them.

Even if a student’s end-of-grade scores don’t back this up, she will feel confident sending a student demonstrating this knowledge to the next grade level.

“Our test scores won’t go up,” Moody said. “They probably won’t go down. I don’t care. We need to change the dialogue.”

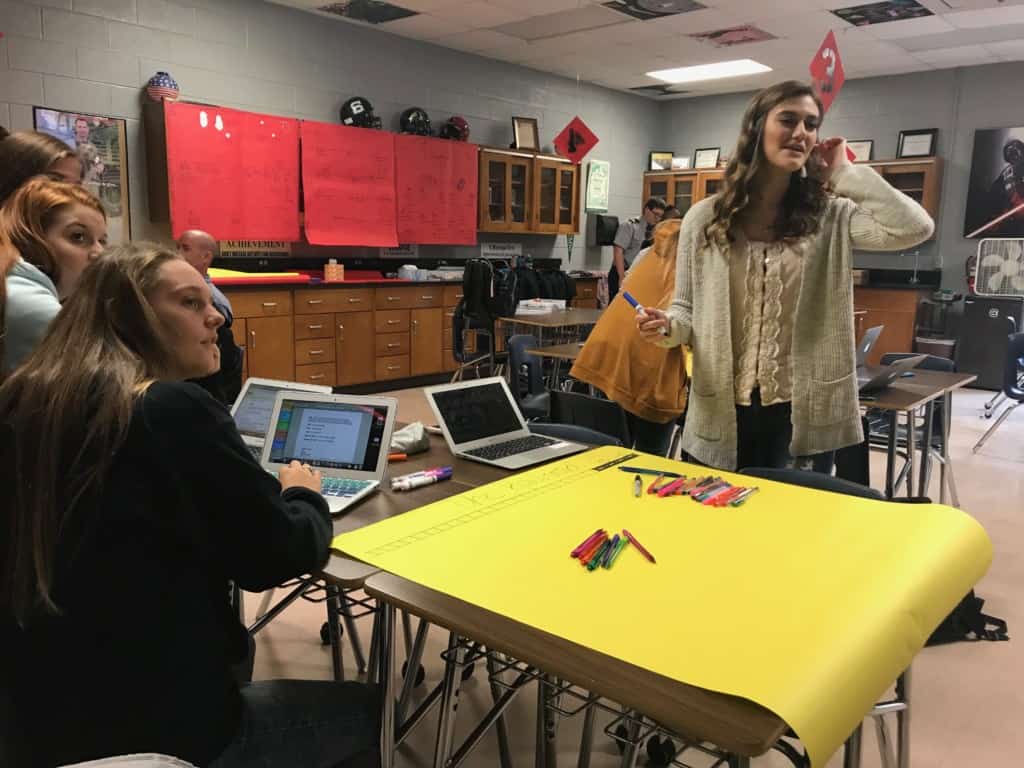

Which she has, and she has her teachers buzzing. Their eyes light up when they talk about designing their lesson plans now, and the creativity oozes out of classrooms as you walk the halls and witness a new kind of teaching.

In Jason Rollins’ American History class at South Rowan High School, Blackstreet’s “No Diggity” is blaring. Students have spent weeks working on websites they built around early 20th century inventions, and now they are working on transferring that effort to a poster board project tracing the future iterations of these innovations. One group is assigned the telegraph, and it isn’t hard for them to connect the ear buds they wear and use to listen to music with the subject of their project.

The students are excited and engaged in the activity, and they’re eager to participate in discussions. The only question is, since ear buds are unlikely to show up on EOGs, how will this learning be demonstrated to the state?

“My initial response was skepticism,” school board member Dean Hunter said. “Wondering why the state would allow us to do this. And, still, one of my questions is, how will the state evaluate our success? We’ve really not gotten a clear response on that, yet.

“We’re excited about it — the possibilities and the opportunity to try some new things with flexibilities [given us]. But I think we’re all anxious to see what will happen. What does success look like? And how long will it take to show progress?”

For her part, Moody seems more focused on fostering the dialogue regarding better and more practical approaches to measuring success.

Her vision, which she hopes will be implemented next year, is using student work to demonstrate learning. RSS students each are given their own device to use from K-12. She wants students to each set up their own digital portfolios on their devices, starting from kindergarten.

At first, the portfolio may just be a photo and answers to questions like, “What is your favorite color” or “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Over the years, the profile will grow and include student work, such as original writing and art, books they’ve read, and budgets they’ve created and balanced in math class.

“My teachers were saying, ‘How would we grade it?'” Moody recalled with a laugh. “Well, why would you grade a student portfolio?”

It doesn’t need a grade, she says. Its purpose is to allow the child to look back on their growth as a person and all they’ve learned. And to give them something to show the community as evidence of what they have actually learned. Students can show potential employers what they’ve read, how they’ve captured their thoughts on the reading, and their ability to communicate through writing.

This, she believes, is far more valuable than whether they identified sarcasm in the fifth reading passage in the second hour of a half-day standardized test.

In addition to technology, which students will need to competently utilize for success post-graduation, the teachers are integrating real-world experiences into learning. Like the experiences Williams, who is now principal of North Rowan High School, had in her elementary school days.

It is important not only to help students connect what they learn in the classrooms to how they will use it outside school doors, but also to ensure that all students are on a level understanding when they address seemingly common conversations and topics.

In homes of affluence, Moody says, parents are permitted the luxury of parenting in conversational language. “What’s your favorite color? What do you want to do when you grow up? Thus, their vocabulary is different,” she says.

In poorer homes, children encounter parenting in business language. “It’s time to go to bed. It’s time to get up. It’s time to tie your shoes,” Moody said. “Those parents are just as loving as any parents, but it’s business language because that’s what’s required to get the job done.”

As a result, all of the students will read a book about a grandfather taking his grandson fishing, but the children will experience the story differently. After all, how can a child relate if he doesn’t know his grandfather? And how can students relate if they’ve never been fishing?

To them, the book looks like “old man with a stick,” said Moody.

At Knollwood Elementary, Principal Shonda Hairston got a field trip approved for first graders for this very reason. Instead of using Title I money to hire tutors, they used some of this money to take the kids fishing.

There was a marked difference in her libraries after the field trip than in previous years.

“There wasn’t a book about fishing or worms in the library to be found,” Hairston told Moody. “Because they couldn’t read enough about it.”

Moody says it wouldn’t be possible to do all this if she didn’t have the leaders she does in her schools and around the district. But others point the finger back at Moody.

“If you are looking at the state to be innovative, you’re looking in the wrong place,” state senator Craig Horn, R-Union, told a group of educators gathered at a NCICU Digital Learning and Research Symposium. Horn then pointed at Moody. “That person,” he said, “is innovative.”

Moody is bucking age-old practices, questioning everything for its efficacy and retaining only those practices that fit the RSS model. One practice out under Moody’s tenure: textbooks.

The district doesn’t budget for textbooks anymore. Principal Kelly Withers can’t remember the last time she bought textbooks for South Rowan High School. The most recent textbooks at her school were published in 2005.

Instead, across the district, teachers are invited to bring their creativity and their judgment to creating original content for students to consume as teaching materials.

“We believe the teachers are in best position to make decisions about what curriculum should look like in that classroom,” Moody said, “and to design that creative and innovative work.”

For the teachers, it means a more rewarding experience.

“I think so much of what I’ve wanted for so long, we can finally do,” said Knox Middle School teacher Sally Schultz, whose classroom doesn’t have any desks. “Our test scores have been awful, but you see in your students how much potential they have and those test scores don’t reflect it. And you see them shut down when they get their EOG scores at the end of the year.”

“And I feel like, finally, we can put the tests aside and teach the kids what they need based on their interests — and they’re just so much more excited to come to school.”

Amie Caudle embraces the extra effort required. For her, it’s personal. Caudle remembers when she was a student, matriculating through a score-based system. She still recalls scoring a 970 out of 1,600 on her SATs and the embarrassment she felt knowing her peers had scored higher.

When she became a teacher, she could identify with her students struggling with tests. She was eager to bring out their inner talents, to show them learning could look like more than an EOG score. Caudle went on to become a teacher of the year at her school, and today is the innovation coach for the entire district.

“I never really achieved well on multiple choice exams,” she said. “But, if you put me in a classroom where I could do a project, where I could become a leader, where I could use some artistic ability — I could excel.”

Providing students this opportunity requires original and customized lesson planning. It means more work, for sure, but the teachers don’t seem to mind. Many don’t even consider it “work,” reporting instead reinvigoration and enthusiasm for their jobs.

“People don’t mind working hard when it matters,” Moody said. “They mind when it doesn’t matter and they just have to put in the time.”

The renewal district experiment has gained statewide and national attention. A lot of eyes are watching RSS and their approach to teaching. There will be difficult moments — surely not everyone will agree with such stark changes to teaching — and the question lingers on how the state will determine success or failure. But Moody isn’t fazed.

“I’m not afraid because I know we’re moving forward,” she said. “It’s challenging. Change is very difficult and maneuvering through the change is slower than I thought it would be. But we’re constantly learning, and we’re excited about what we’re doing here.”