Should students who take internships be paid? The clear answer should be yes. And yet, in North Carolina and across the nation, unpaid internships have become all-too-common, and many high school and college students find themselves impelled to work without compensation in hopes that they eventually will gain an advantage in the job market.

One such student visited me in my UNC-Chapel Hill office this week. Working part-time for a nearby news organization while a full-time student, he had produced a fine feature that got a bounce in social media. Are you being paid? I asked. He smiled, said he got no pay, but wanted the experience.

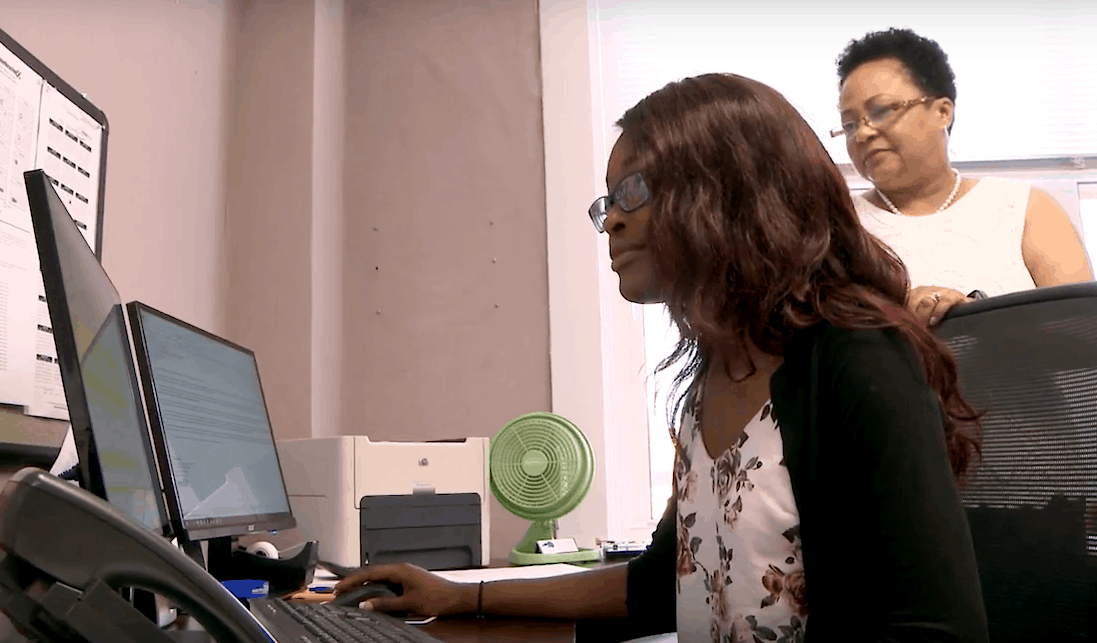

As an EdNC series highlighted earlier this week, the State Employees Credit Union Foundation two years ago launched an initiative that offers students both valuable experience and pay. In collaboration with nine universities, the SECU foundation provides $5,000 stipends to 20 interns who agree to work in underserved rural communities: Good for students, good for the communities.

Reading the series brought to mind a couple of my own experiences – one as a student, one as a university faculty member.

I still recall the rush of excitement and nervous anticipation that came with the arrival of a thin-yellow-paper telegram – a quaint artifact of pre-digital media – from The Washington Post offering me an internship for the summer of 1969. The Post paid interns the prevailing entry-level wage, gave me reporting assignments that resulted in published stories, and assembled the interns for weekly seminars with veteran journalists and public figures.

Then, a few years ago, I had to face the question of pay-or-no-pay internships at a faculty meeting of the UNC School of Media and Journalism. We had a debate over whether the school would agree to give one-hour academic credit to students who got unpaid internships – as a trade-off for lack of pay. I was in a small minority who voted no, though I fully understand that my colleagues, grudgingly, wanted to keep options fully open for students.

My concern then, as it is now, is that an unpaid internship amounts to Mom and Dad, in effect, subsidizing a media company by supporting their child in a big city through the summer. More seriously, unpaid internships favor the affluent over students in families of more modest means. (Earlier this week, the School of Media and Journalism announced that two UNC alumni have funded an effort to lower barriers to internships for students on need-based financial aid.)

A year ago, Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, decried what he called “America’s broken internship system’’ for fostering inequality of opportunity. Writing in The New York Times, Walker recalled his own experience as a “low-income kid from a small town’’ whose internship in the Texas legislature “equipped me with the skills, confidence and relationships’’ to propel his career.

Employers, he said, “should not only compensate students for their time and contributions, but also eliminate barriers that prevent low-income and underrepresented students from pursuing these opportunities.

In media-related businesses, paid internships have fallen in the face of the erosion of daily newspapers and glossy magazines. Tight budgets have pinched internships in government and nonprofits. What’s more, there has been a fall-off in summer employment and a decline in government support for summer jobs for young people.

On its website, the North Carolina Department of Commerce has a short paper and data charts on the “decline in summer youth employment.” Its analysis cites unpaid internships as a factor:

“In particular, the Great Recession seems to have had an outsized impact on the younger population’s labor force participation, which fell from around 68 percent in 2005 to a low of 52 percent in 2011. This began to rebound slightly during the economic recovery, but has declined yet again. Some theories that have been offered as to why youth labor force participation has been declining include: crowding out of younger individuals by older ones seeking work, the rise of volunteer or unpaid internships (which do not show up as work), and other extracurricular activities to improve their college applications.”

Earlier this year, The Atlantic offered a more upbeat assessment of students and summer employment. While it recognized the “extraordinary rise in unpaid internships’’ among an array of factors, The Atlantic pointed to data showing that “ teens are remaining in high school longer, going to college more often, and taking more summer classes.”

In the long run, high school students would benefit more from a longer school year, even if that diminished their employment in food service and other low-skill jobs. For college students, internships matter a lot, and government, private companies and foundations have a responsibility to restore the paid internship as the norm.