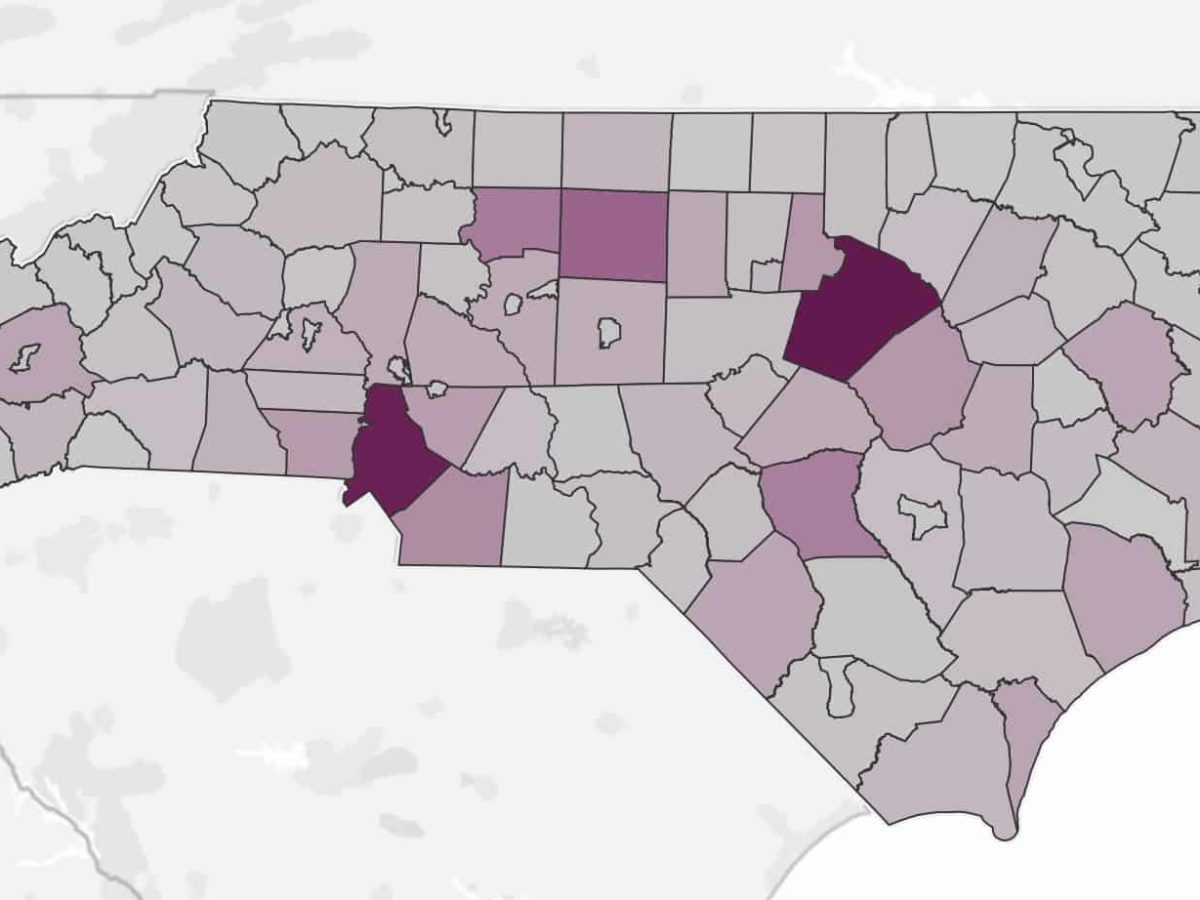

We’re 115 school districts in the state of North Carolina. Many are small: 29 less than 3,000 students, 41 less than 4,000 — with our two smallest districts exceeding just 500 kids. Some 15 are still independent as “city” districts. Consider that the primary corridor running through the state, along the Piedmont crescent, captures half of the state’s population, grounded by Charlotte-Mecklenburg in the south and west, and Raleigh-Wake in the Triangle in the north and east — each holding around 10 percent of the state’s students. In many respects, we are two North Carolinas: urban, largely in the Piedmont, and rural, focused in the east and the west. And the population trend is toward urban, with many rural settings actually shrinking in size. Dwindling tax bases are stressing the local ability of many of our counties to meet the educational needs of our children.

In many respects, we are two North Carolinas: urban, largely in the Piedmont, and rural, focused in the east and the west.

What can we do about this? Let’s talk about consolidating districts, a political hot potato. There may be common ground on this issue because of the greater efficiencies and, more importantly, the greater educational benefits at stake for our children. Consider what might happen if we required districts to have at least 15,000-20,000 students:

- Less duplication and more critical mass to central office capability, most especially around curriculum/instruction support to the field

- Greater size/scope, which should attract stronger talent at the superintendent level

- Stronger superintendent talent should attract stronger talent to the field, whether in the classroom or the principal’s office

- Better boards: as districts are consolidated, hypothetically stronger candidates are recruited overall from former boards that are no more — which can lead, in turn, to better recruitment of talent in the district

- Better utilization of schools as efficiencies are addressed across former district lines

- With better schools, serving students better, does not a better workforce ultimately unfold? Better workforces facilitate improved industry recruitment, which should yield more jobs and improved local tax bases. The results feed in a positive way upon each other.

Current trends here do not bode well for kids in rural sections of the state, where our small districts reside. And we can’t afford for the gulf between these two North Carolinas to widen.

Why would we not try this? Given the present inhibitor of perceived political consequence, does it not make sense to incent communities to try this? Perhaps test the landscape with four or five pilots and monitor the outcomes. As one considers this, also consider the downsizing of DPI, present budget negotiations notwithstanding. In the absence of a strong DPI, many of these small districts would have little-to-no support, their budgets stretched, their central offices woefully short — all exacerbated by both size and low wealth. Current trends here do not bode well for kids in rural sections of the state, where our small districts reside. And we can’t afford for the gulf between these two North Carolinas to widen.

This will take some political courage. With both efficiencies (translating to savings) and an improved educational service delivery model (right for our kids), why would we choose to do otherwise? I don’t buy the arguments of geographical challenges or “this will never work.” With resources stretched and academic gains at risk, we have no option other than to get creative around our current models that many would say are outmoded. It’s time to take some risk to get greater returns.