Public colleges and universities (including community colleges) represent the largest sector of undergraduate higher education in the United States. In the fall of 2023, community colleges and public four-year universities enrolled 73 percent of all undergraduate students. These institutions receive most of the public state and local funds designated for higher education, but the level and composition of funding varies across states and institution types.

State funding formulas have historically directed significantly more money toward four-year institutions than to community colleges — a trend that has continued even as community colleges are increasingly relied upon to train and educate students for high-demand jobs. What does state and local funding for community colleges look like across the Fifth District? Does the distribution reflect the changing dynamics of higher education?

How does state and local funding work?

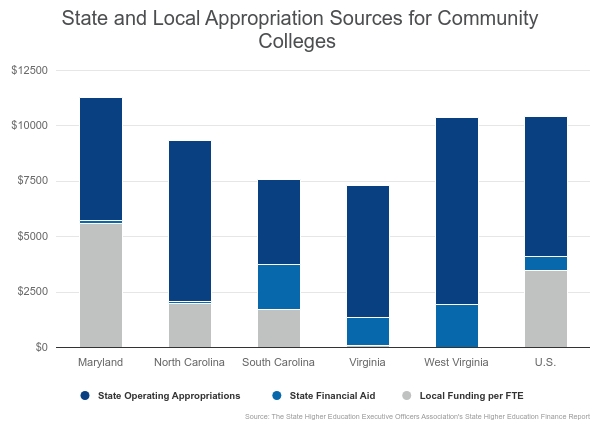

Public higher education is funded largely through a combination of state funding (appropriations and financial aid), federal funding (financial aid and grant money), local tax revenue, and revenue from tuition. As we wrote last fall, community colleges primarily rely on a combination of funding from state and local appropriations, in addition to tuition revenue and federal financial aid. State financial aid also plays an important role in some states: South Carolina’s LIFE and HOPE scholarship and West Virginia’s Promise Scholarship provide colleges with considerable revenue. In most states, community colleges receive lower levels of per-student state funding than their four-year institution peers, but unlike four-year institutions, they commonly receive funding from local tax revenue.

State appropriations for higher education are allocated through the annual state budget process. Once state revenue is allocated to higher education, the state’s education agency distributes funding to the institutions. Each state employs a unique approach to dispersing the funds based on schemes and formulas of varying complexity. In the Fifth District, most states divide the higher education budget based on a combination of institution type and full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment, but there is still variation. In South Carolina, they do not use an explicit formula to fund community colleges, but in Maryland, they use a very specific formula that mandates that community colleges receive 29 percent of the state funding amount allotted to four-year institutions.

State and local appropriations for higher education are trending higher overall

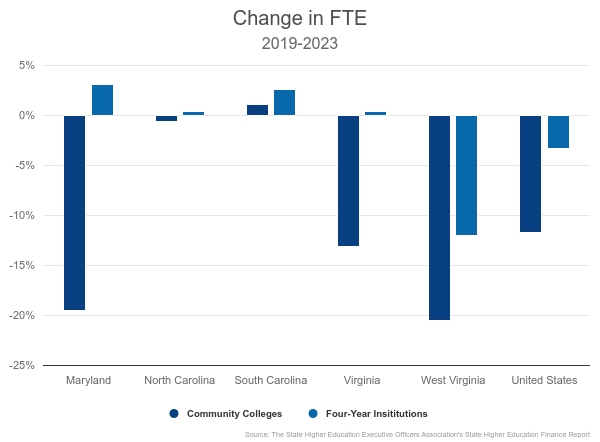

The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association’s State Higher Education Finance Report for fiscal year 2023 shows growth in FTE funding nationally. These increases are being driven by two factors. First, there has been continued support for higher education, with total state and local appropriations growing by 4.4 percent (after adjusting for inflation) between 2022 and 2023. At the same time, overall FTE enrollment has been falling in recent years, declining an additional 0.5 percent in 2023. In some states the decline has been rather dramatic, with one-year declines that exceed 2 percent in 12 states, including West Virginia.

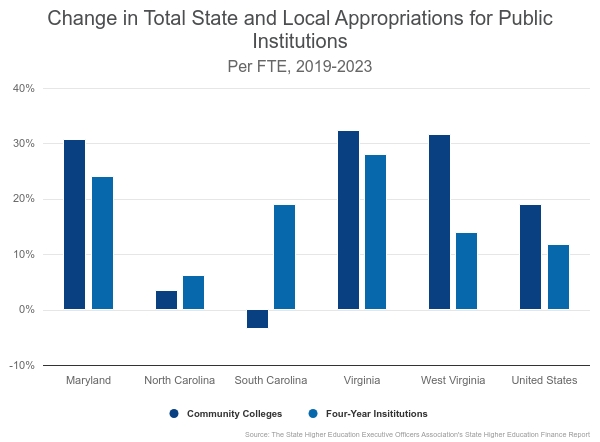

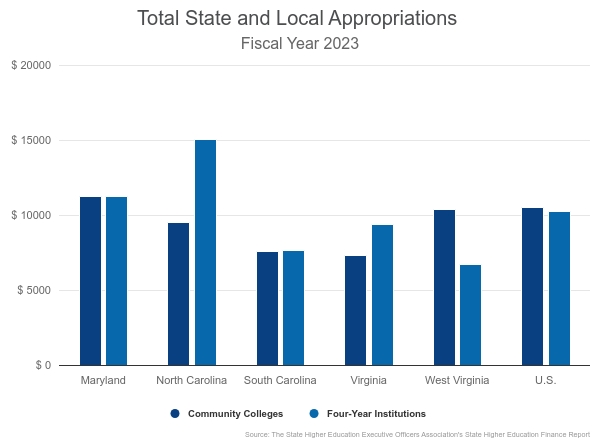

Nationally, since 2019, per-FTE state and local appropriations for community colleges have grown 18.9 percent while appropriations for four-year institutions have grown 11.7 percent (in real terms). All sectors and states in the Fifth District have seen increases except for South Carolina community colleges.

Some of this variation is due to changes in absolute funding, while some is due to changes in FTE enrollment. This can be seen more clearly by examining individual states across the Fifth District, which have experienced rather dramatic differences in enrollment changes since 2019. While some states have seen double-digit declines in FTE enrollment (especially at community colleges), North and South Carolina have seen overall increases in public higher education institution enrollment.

These enrollment declines can ironically result in higher per-FTE revenue. For example, in Maryland, total state and local appropriations for community colleges grew by just 5.3 percent between 2019 and 2023. At the same time, however, enrollment fell by 19.5 percent. Because there were fewer students to spend the increased dollars on, per-FTE appropriations rose by 30.7 percent.

Has funding kept up with the evolving role of community colleges?

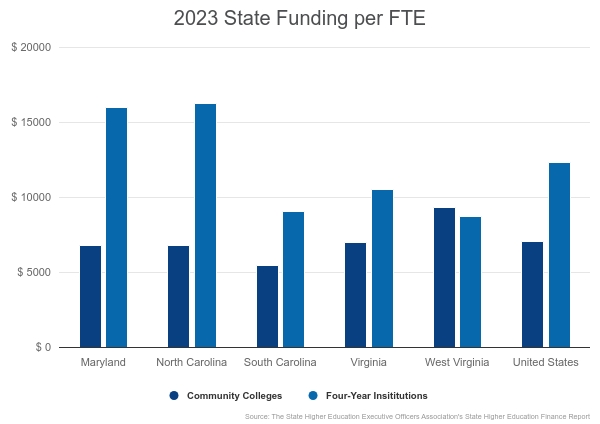

In four out of five states in the Fifth District, state funding per FTE, which includes appropriations and state financial aid, is higher at four-year institutions than at community colleges, with four-year institutions getting an average of $12,936 per FTE in state funding and community colleges getting an average of $6,672 in 2023. In the Fifth District, West Virginia has the highest per-FTE level of community college state funding and is the only state where community colleges receive higher levels of state funding per FTE than their four-year institution counterparts.

Unlike most four-year institutions, community colleges commonly receive local aid as well as state support. Community colleges in 29 states receive some funding via their local governments, ranging from very small amounts in states like Virginia, to very significant amounts in states like Maryland. In the Fifth District, all states but West Virginia provide some level of local appropriations for community colleges.

When considering both state and local appropriations, community college funding looks more robust. Nationally, after considering local appropriations and state financial aid, community colleges and four-year institutions receive relatively equal levels of state and local funding, with community colleges receiving $10,488 per FTE and four-year institutions receiving $10,238 per FTE. However, it varies considerably across Fifth District states: Four-year institutions in North Carolina and Virginia receive considerably more state and local appropriations than community colleges. The situation in West Virginia is the opposite: Community colleges receive higher appropriations per FTE than four-year institutions.

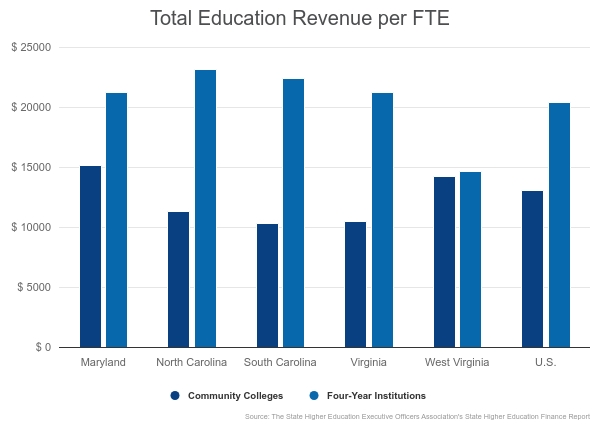

While state and local appropriations represent an incredibly important funding source for public institutions of higher education, net tuition revenue — defined as the total amount of revenue institutions receive from tuition after subtracting all institutional student grants and tuition discounts — also plays an important role. Net tuition revenue tends to be much higher at four-year institutions than at community colleges, where tuition is typically much lower.

When considering total education revenue — defined as total state appropriations plus local funding (not used for capital spending) plus net tuition revenue — very large revenue gaps between community colleges and four-year institutions in all Fifth District states emerge, except in West Virginia, where four-year institution revenue is far below levels observed in other states.

Challenges ahead for community colleges

When considering state and local appropriations alone, funding gaps between community colleges and four-year institutions do not appear stark. However, after examining total education revenue, considerable gaps exist both nationally and across most Fifth District states. The question is whether this is appropriate.

Outreach to community colleges across the Fifth District indicates that the cost structure of community colleges is undergoing a transformation, which is leading to financial stress among institutions. Student demand is moving away from traditional associate degree programs, which are generally the lowest cost for schools to offer, and toward high-demand technical programs, such as nursing, welding, and mechatronics. These programs require expensive equipment and faculty that earn higher wages than many other community college instructors. In addition, community colleges are now providing a much broader set of wraparound services than the past, ranging from mental health counseling to food pantries. In most cases, funding formulas have not been adjusted for this new reality, although it’s important to note that North Carolina currently has a proposed funding formula under consideration that would be a big step in that direction.

Many community college leaders feel resource constrained in ways that seem different from their four-year counterparts. This could get worse over time as student demand at community colleges shifts to high-cost technical programs. The cost of executing these programs is ever-increasing, and it far outweighs the cost of teaching traditional general education courses. As these changes occur, the gap between instruction costs at community colleges and four-year institutions is likely narrowing considerably.

Community colleges have the need and desire to offer high-demand, high-wage programs while also remaining a very low-cost option for students in their service areas. With large revenue gaps between community colleges and four-year institutions, this is a precarious balance as community colleges strive to be an attractive option to students, employers, and staff.

Editor’s Note: Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System. The Fifth District includes the states of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina; 49 counties constituting most of West Virginia; and the District of Columbia.