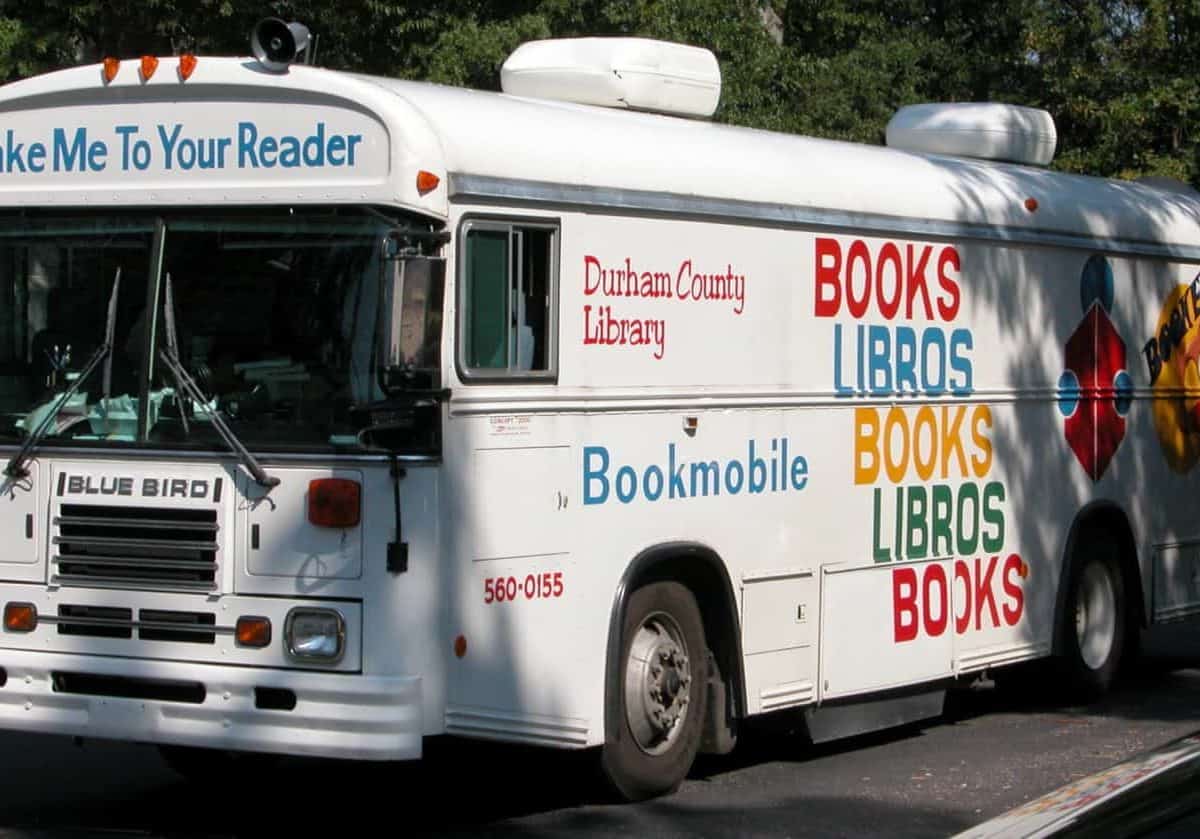

When I was asked to join in the pre-Christmas spotlight on books, my mind turned to memories of the bookmobile. During the summers of my early adolescence in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the lumbering van would pull up near the intersection of Finchley Ave. and Winthrop Ave., and Momma would send us out to borrow enough to read for a week or two.

My parents, who grew up in rural Cajun towns and moved to the city after they married, subscribed to the daily newspaper, and I recall a few Readers’ Digest publications at home. But housing, feeding, and clothing a burgeoning family (eventually reaching 10 children) left no surplus for buying books.

During summers, Momma imposed a two-hour “nap time’’ to keep us out of the midday sun. In the room I shared with two brothers, we listened to radio broadcasts of major league baseball and read the books we checked out from the bookmobile — mostly light sports fiction and short idealized biography and history, nothing classic or especially literary.

From my own experiences, two lessons emerge: First, that an investment in a public institution — the library that sponsored the bookmobile — can pay off in touching young lives. Second, that in encouraging young people to read, it is better that they read whatever books engage them, short of coarse and schlocky, rather than have them reject heavier reading imposed by adults.

By mid-to-late adolescence, my reading had expanded beyond bookmobile fare. In addition to high school reading assignments, I spent a summer enthralled with Graham Greene: The Quiet American, The Heart of the Matter, and The Power and the Glory.

Over the past year or so, I have revisited Greene, not only rereading what engaged me as a teenager but also reading what I had too long passed over. In Brighton Rock, Greene delivered one of those pungent opening sentences that sticks in memory: “Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him.”

In addition to Greene, my taste in fiction runs to Walker Percy, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, Ernest Gaines, and Ward Just. Mostly, however, I read what I need for the work I do in teaching and writing at the intersection of journalism, politics, and policy. A current project has sent me to researching the transition from the 1960s to the 1970s, and I am now reading Lawrence O’Donnell’s Playing with Fire: the 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics.

Over the past two weeks, I have experienced anew the power of book-length storytelling as reflected in the final papers of the 45 students in my “Talk Politics’’ class in the semester just completed at UNC-Chapel Hill. In this class, as in my “Southern Politics’’ classes over the years, I let students choose from a list of nonfiction books by journalists on elections, issues, and trends. I assign the classic All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren as the capstone of the course. Through their reading and our discussions, they learn that Warren’s novel is not a rollicking Southern politics story but rather a deeper meditation on ethics, power, human frailty, and love.

One student produced a compelling, provocative essay on how citizens who are wont to psychoanalyze people in power “ignore their own part in creating the current social climate in America.” Students wrote papers on “ambition vs. ego,’’ on “the power of knowledge’’ and the “danger of truth without thought to consequences,” on the persistence of populism as well as the “implications of race,” and on the potency of voice and rhetoric.

Today, just as metropolitan newspapers have diminished in competition with online media for people’s attention, so books now compete with Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat and such. Books, too, come in audio and digital, as well as on paper.

In an interview with The New York Times, Walter Isaacson, author of a new biography of Leonardo da Vinci (which I just bought), noted that he drew on the Renaissance artist’s notebooks, of which 7,000 pages survive. “Paper turns out to be a superb information-storage technology, still readable after five hundred years, which our own tweets likely (and fortunately) won’t be,” Isaacson said.

The Times Book Review regularly asks authors, “What book might people be surprised to find on your shelves?” Well, I do not qualify for such a Times interview, but I would respond that for reading-as-a-diversion, I turn to James Lee Burke’s “Dave Robicheaux’’ novels. Burke has churned out more than 20 books in this series of stories of a Vietnam veteran who loses his first wife and job as a New Orleans detective to alcoholism and goes on to fight crime and corruption as an unorthodox deputy sheriff in New Iberia, a small city on Bayou Teche.

In the course of these novels, Robicheaux’s second wife is murdered, and he subsequently marries a former nun who had moved to Louisiana to support exploited sugarcane workers. He adopts a daughter, Alafair, after he rescues her from a plane crash in the Gulf of Mexico. Robicheaux is abandoned by his mother, who also ends up killed. (Her last name is Guillory). Burke delivers gritty escapism about an endearing yet troubled soul trying to do right, written with a flair for depicting the natural environment of the bayou region.

Inc.com, the website of a magazine about small businesses and start-ups, recently posted a column headlined, “Why You Should Surround Yourself with More Books Than You’ll Ever Have Time to Read.” Clearly, I find myself in that category — and the compulsion had its genesis as the public library bookmobile came around and Momma gave us permission to borrow some books.

Recommended reading