As many child care centers across the state struggle to make ends meet with low enrollment, Brenda Flowers, a home-based child care provider in Rocky Mount, has been getting calls left and right.

“Lately it is like, boom,” said Flowers, owner of Little Kings & Queens Daycare. “Everybody’s calling me.”

Flowers, who has owned and operated the business for more than 20 years, said she’s hearing from new parents interested in a smaller setting with flexible hours. She wants to expand her business and plans to hire a teacher soon.

In North Carolina, early education leaders are looking to home-based providers, often called family child care homes, to fill shortages in infant and toddler care and meet parents’ evolving needs.

“I think this pandemic has proved that the part of our delivery system that often gets overlooked actually has some great benefit,” said Safiyah Jackson, early childhood systems director at the North Carolina Partnership for Children (NCPC).

NCPC is the statewide organization of Smart Start, a network of 75 local partnerships that serve as hubs for early childhood programs and services. The organization is using part of its $5 million CARES Act allocation to give home-based child care providers a 12-month subscription to Wonderschool, an online platform built for child care providers to help manage their businesses and market their services. Smart Start will also coach providers on the best ways to use the platform. So far, 180 home-based providers have opted in. Providers can sign up here.

More than 1,500 licensed child care homes across the state were serving about 6,300 children from infancy to 5 years old in 2019, according to a recent Child Care Services Association (CCSA) workforce study. A policy paper from Home Grown, a national initiative advocating for home-based child care, says the supply of home-based care has decreased dramatically across the country in the last decade, largely because of financial challenges.

Pay remains low, and home-based providers often do everything themselves. The median hourly wage for home-based child care providers was about $9 in 2019, according to the CCSA study. In comparison, the study found that average wages for center-based teachers ranged from $10.50 per hour for starting teachers to $15. Child care center directors made an average of $19.23 an hour.

Low-income children, as well as Black and Latinx children, are more likely to attend a home-based facility than white children and children from high-income families, according to Home Grown. Infants and toddlers, children living in rural areas, and children whose parents work nontraditional hours are more likely to rely on home-based care than centers.

“Often the most familiar, flexible, convenient, personal, and affordable option for families, home-based providers frequently meet the needs of children and families not otherwise served by the current child care system, illustrating the unique, intersectional importance of their work,” the policy paper says.

‘So many hats’

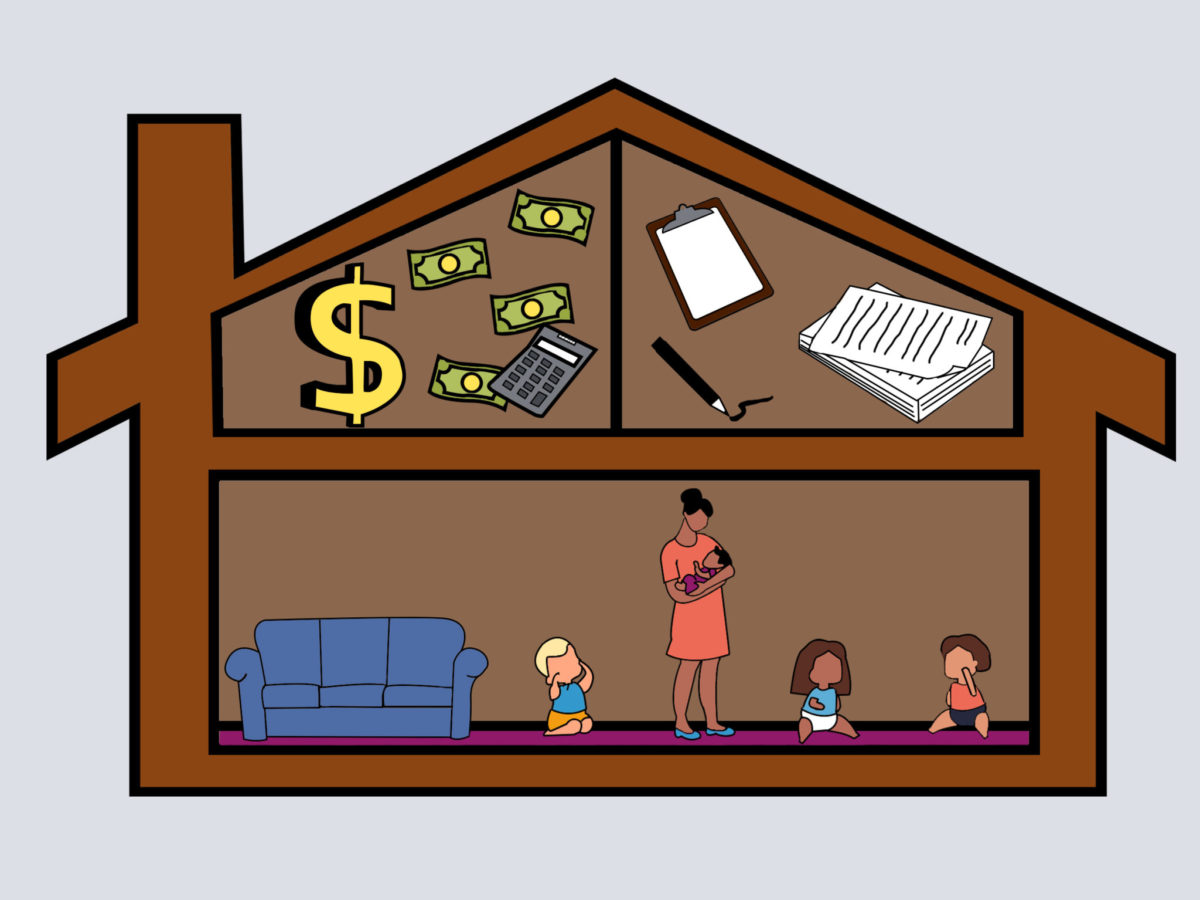

Home-based providers are often overwhelmed with a wide variety of responsibilities, said Louise Stoney, a consultant specializing in early childhood finance and policy who is working with NCPC on the Wonderschool initiative. Stoney, also the co-founder of Opportunities Exchange and the Alliance for Early Childhood Finance, described the tool as “Airbnb for child care.”

“You have one individual that has to wear so many hats that it is completely crazy,” Stoney said. “So they are literally spending all their day working with children. They are the teacher in many cases, or the co-teacher if they happen to have an assistant. They are the director. They are the person who deals with families. They are the marketer. They are sometimes the chief cook and bottle-washer. They are everything.”

Flowers said her average day starts about 5 a.m., when she picks up her first round of children. She picks up another bunch at 7:30 a.m. Children stay in her home until 10 p.m.

“It’s a long day, but I’ve got a goal in mind,” she said. Flowers said she is eager to gain access to Wonderschool through her local Smart Start partnership, the Down East Partnership for Children (DEPC).

She said the tool will help her keep better track of her business’s finances, allow her to save more money and time, and keep better track of parents as they sign in and out.

“There’s a lot of administrative details that go into running successful businesses, and you’re exhausted,” Stoney said. “What we really want is for people to focus on kids. So what a tool like Wonderschool does is to basically help take off the shoulders of these small businesses a lot of this routine paperwork, business management, that can easily be automated.”

Jackson with NCPC said the organization held focus groups with home-based providers early in the pandemic and found most were still using pen and paper to do everything. She said home-based providers also sometimes miss early childhood resources or growth opportunities since they have so much on their plates. The platform will help providers plan, manage expenses, and collect fees from parents.

“They’re better able to track their payments, and track their expenses, and project when cash flow is going up and down, and that inadvertently allows a better financial position,” she said.

Serving the youngest children

In rural parts of eastern North Carolina, home-based providers are offering care when no one else is, said Henrietta Zalkind, DEPC’s executive director.

“There are homes in places where there’s not enough kids to have a center,” Zalkind said. She said her partnership, which serves Nash and Edgecombe counties, has reached out to home-based providers over the years to help them become licensed so they can participate in public programs like child care subsidy.

“In rural counties, if there aren’t child care centers, someone has to be taking care of those kids, and it’s really important to quality, sustainability, and improvement to have those folks be licensed,” she said.

Zalkind said home-based care has always been key in the area to serving the very youngest children. Infant and toddler care is more expensive than care for preschool-age children. As the pandemic stretches centers thin financially, some centers cannot afford to offer care for infants and toddlers. Jackson said home-based providers often can provide this care when centers cannot because of lower staff costs, smaller ratios, and less overhead expense.

“Child care homes and providers provide such a wonderful, intimate and developmental environment for infants and toddlers, and it’s … more fiscally sound to do that,” she said.

Jackson said she also hopes the perception of home-based child care can shift, and that providers can be a larger part of funding and policy conversations.

“Home-based programs are usually seen as less professional, less agile — they’re just seen as ‘less than,'” she said. “But with a web-based presence, with a way of managing their business in a very modern, relevant way, this is going to help to increase the parity and perception of home-based programs.”