|

|

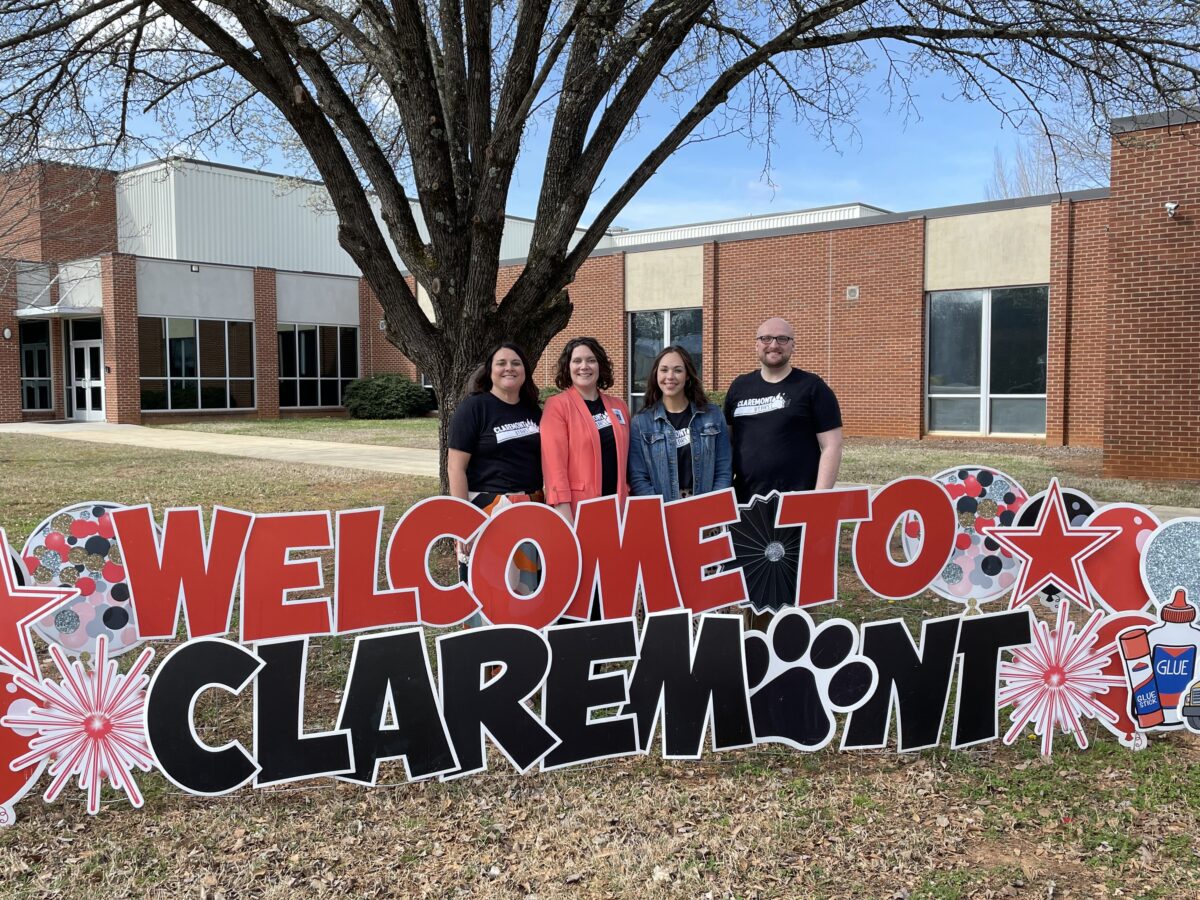

Claremont Elementary School in Catawba County Schools welcomed educators, community members, and N.C. Department of Public Instruction representatives to their Equity and Excellence Expo on Feb. 22.

One is too many

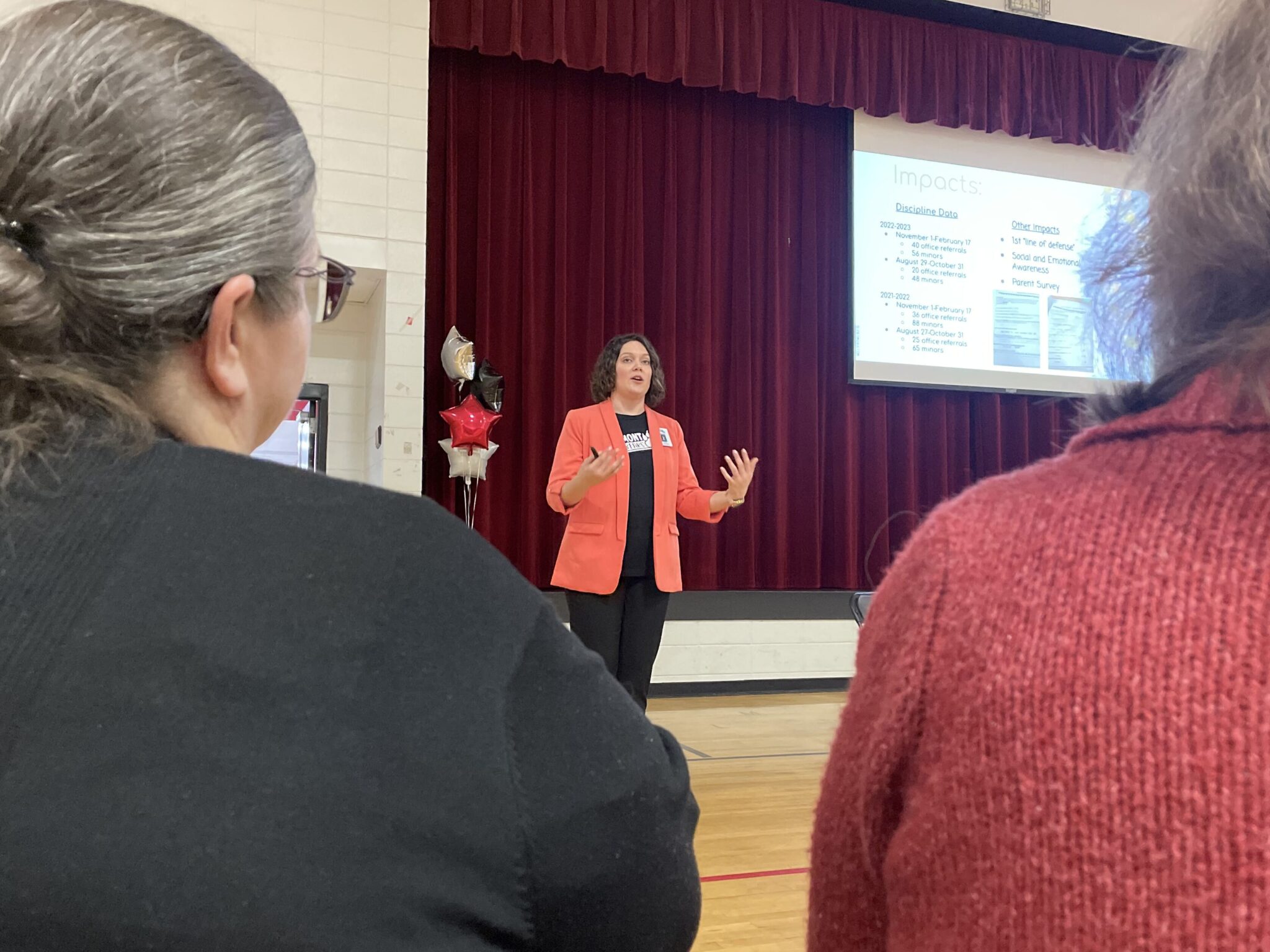

According to Assistant Principal Katie Lunsford, combing through school data helped Claremont’s team develop a more intentional focus on building relationships at the school and a sense of belonging and connectivity to staff. They specifically looked into Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS) reports and student surveys. This included examining student participation in positive behavior incentives and opportunities to create more student buy-in.

In addition, school counselors helped leaders recognize that “students weren’t able to identify their emotions,” Lunsford said. “They couldn’t say if they weren’t angry, or happy, or sad, or they might have been able to, but they didn’t know what to do with it afterwards.”

What spoke to the core of change was the observation, and thus, prioritization of students’ mental health. Lunsford expressed that one too many of her students reported not wanting to be here anymore. This propelled Claremont’s team forward with finding a solution.

You don’t have to behave to belong

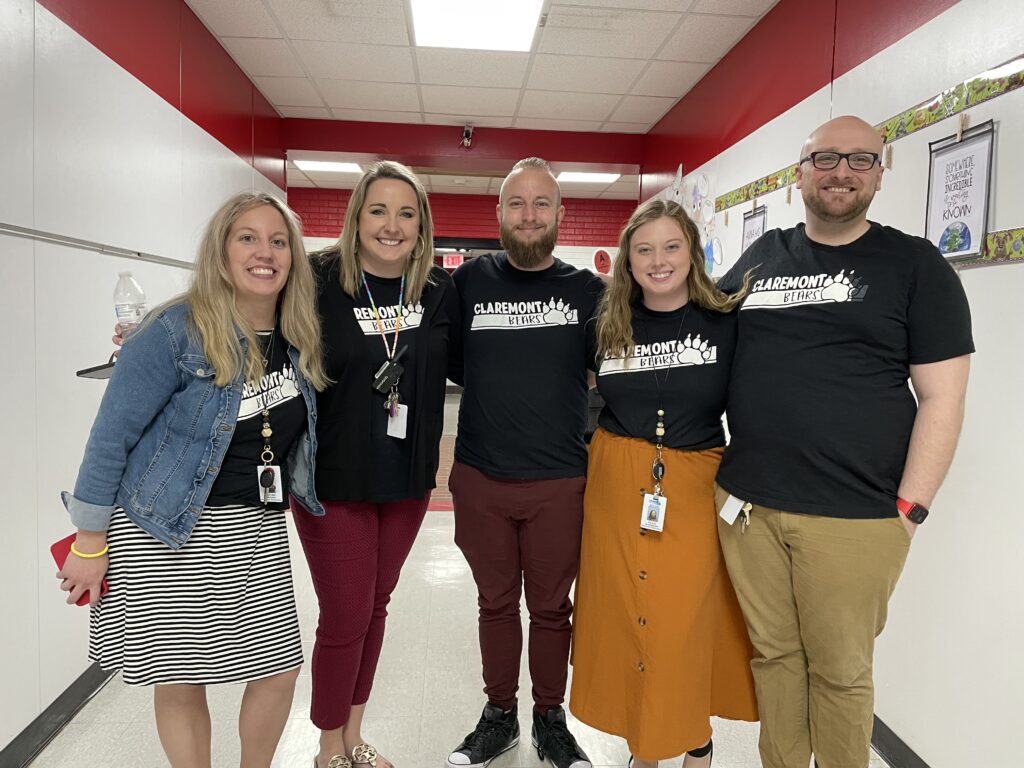

Having recognized the need for students to feel safe and able to connect with at least one adult in the building, the Relationship Task Force was formed late last school year. Entering into the new year, their first objective was to target staff-to-staff connection, creating a model of engaging with one another in the way that they would eventually encourage students to do so as well.

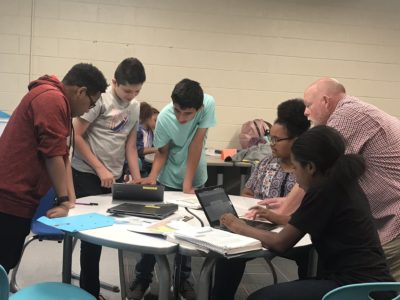

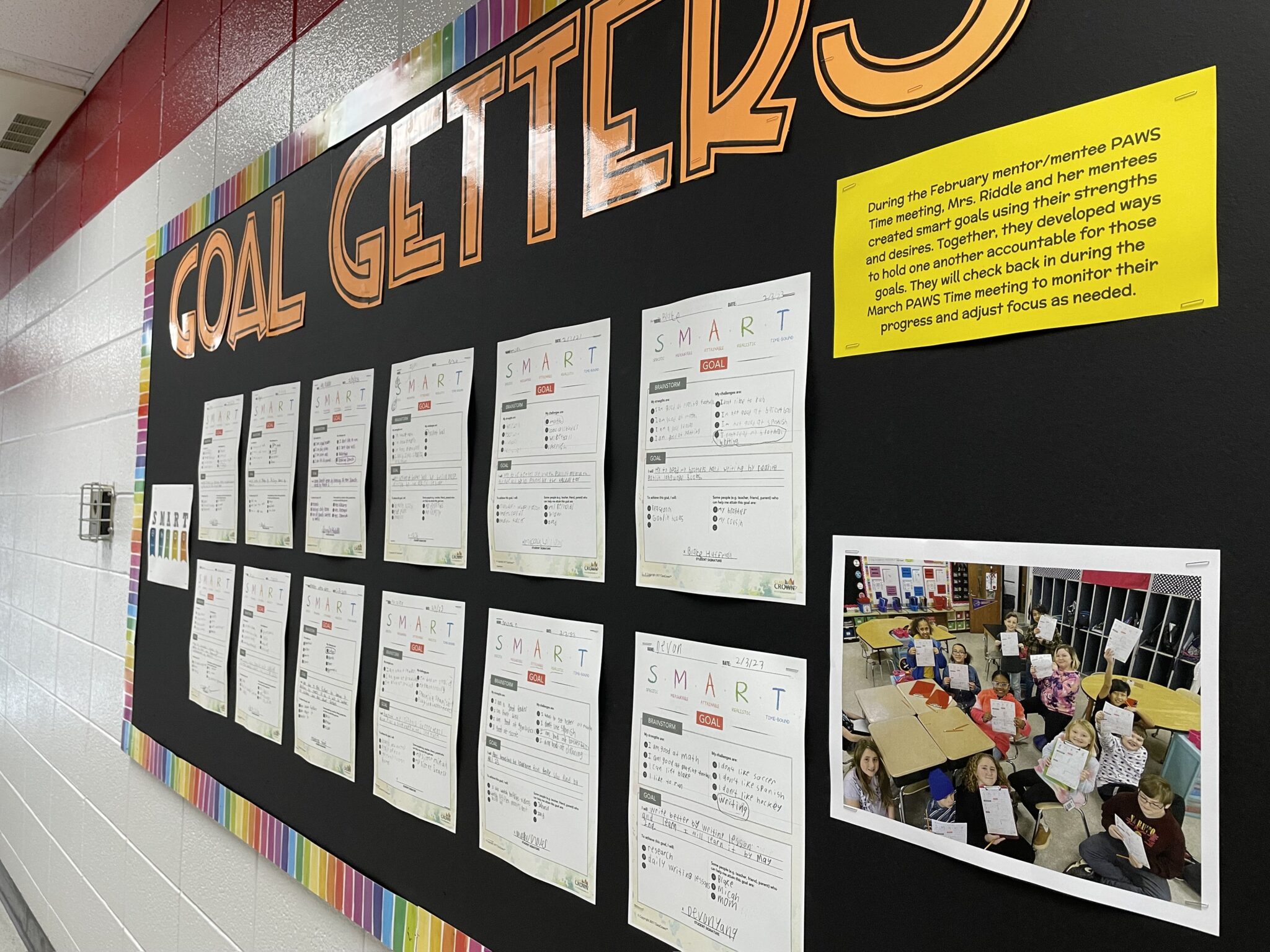

From there, the mentoring initiative was born. The program connects every staff member with a small group of students to mentor. While staff identified students that possess strong bonds to be mentees, students ultimately have choice in the selection and can be reassigned.

According to second grade teacher Christian Underwood, not only are children able to check in with mentors during “Grand Central Station,” or morning homeroom periods, but “Paws Time” is also offered one Friday each month. This provides 30 minutes dedicated to pausing to engage in a guided conversation in their mentoring groups.

In her closing remarks, Lunsford emphasized the impact on discipline data now that mentors have been added as an additional layer of support with student behavior.

“We are not looking at punishing children. We’re looking at changing those behaviors,” Lunsford said. “We want students to know when they walk in this building, they belong. You belong here, you are loved, you are seen, you are heard.”

For them, behaviors will change afterward, but the first priority is the relationship.

Relationships are the foundation of personal learning

Cierra Winstead is Claremont’s math and personalized learning academic facilitator. She knows firsthand the significance relationships have played in creating learning experiences tailored to each individual student in the school.

“You cannot provide equity for students if you don’t know them. You cannot raise them to excellence if you don’t know them. You cannot personalize their learning if we don’t know them.”

Ms. Teri Eller, kindergarten teacher and multi-classroom leader for behavior

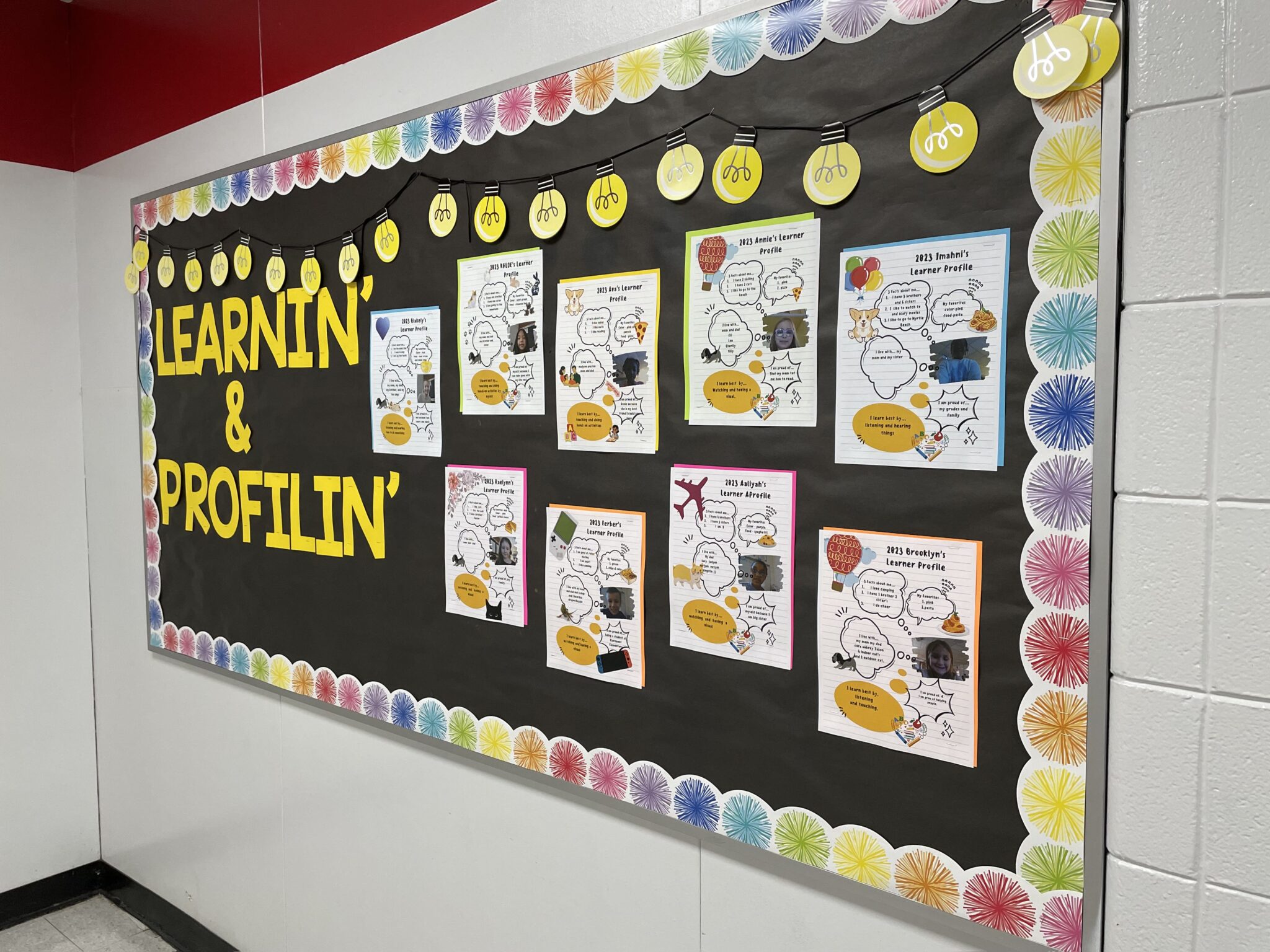

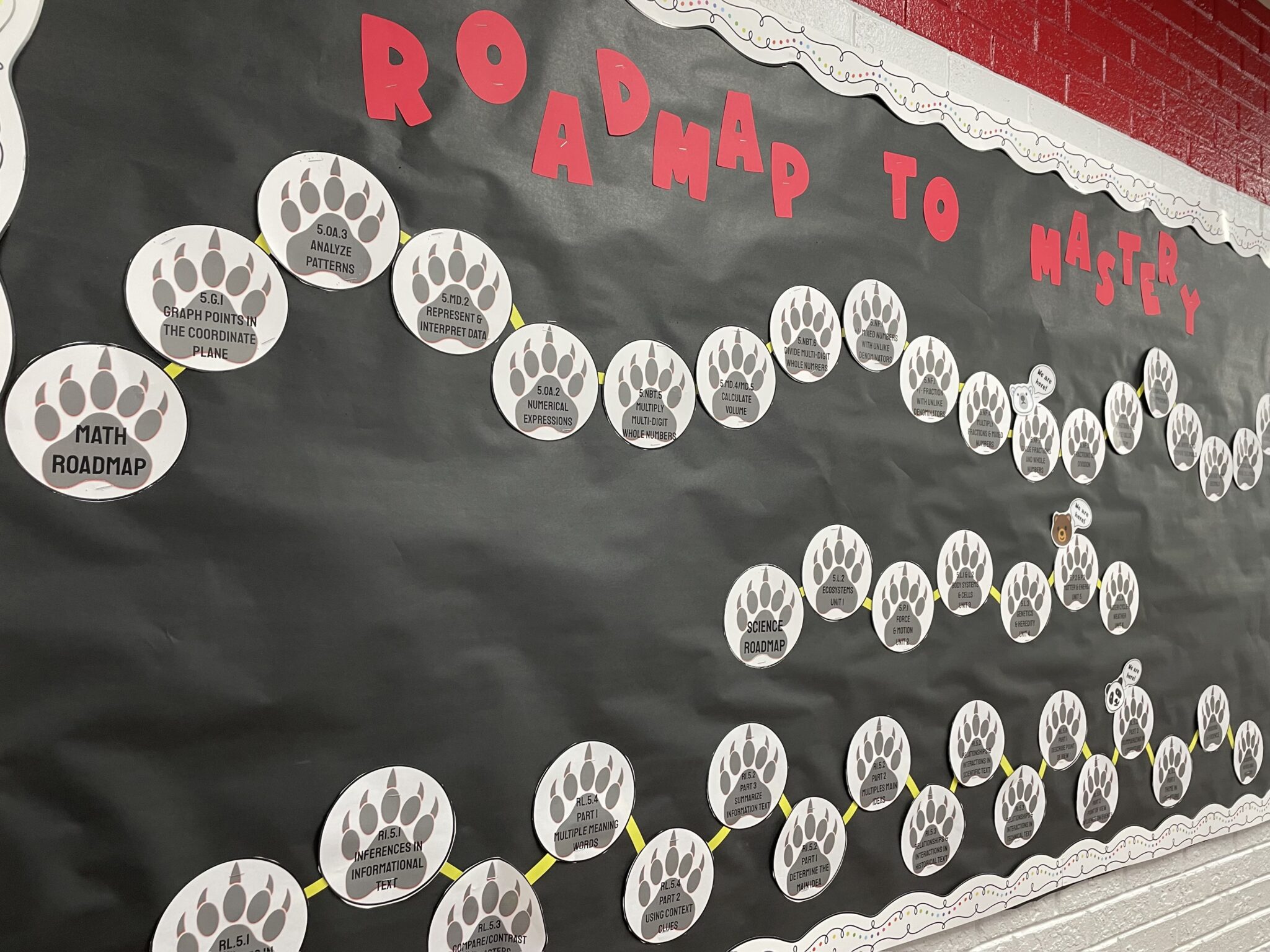

Data drives all instructional decisions. Winstead acknowledges that it is a hefty journey that is “built upon data-driven decisions, student relationships, learner profiles, and instruction tailored to students’ needs.” She said the foundational components of personalizing learning include:

- Unpacking standards and creating learning targets.

- Examining pre-assessment, formative, and summative data.

- Differentiated core, small group instruction, and independent practice based on student data.

Regarding the last component, in Claremont’s philosophy, “students or relationships are at the center of all that we do.” Winstead feels that she “can’t have those crucial conversations and make the teacher feel that it’s okay to be vulnerable with me if I don’t have a relationship with them.”

Learning both ways

James Frye, Claremont Elementary’s principal, said that he has taken a flat leadership approach, prioritizing staff contributions to decision making and also learning from students.

“I think having that touch point where I have children that are students daily in this environment in this culture, who are coming to me and spending time with me and telling me about their lives,” he said, “and everything has humbled me and kept me centered and focused on what’s important.”

Ashley Arndt, structured literacy and title one academic facilitator, said when she was a student at Claremont, relationships were always at the forefront of culture at the school.

“Now,” she said, “we’ve magnified it to a bigger scale.”

She noted that, like with anything new, staff initially expressed some skepticism. Additionally, staff collectively spoke to overcoming obstacles along the way. Through a consensus among the team, they are sure to be able to face challenges as they continue through iterations.

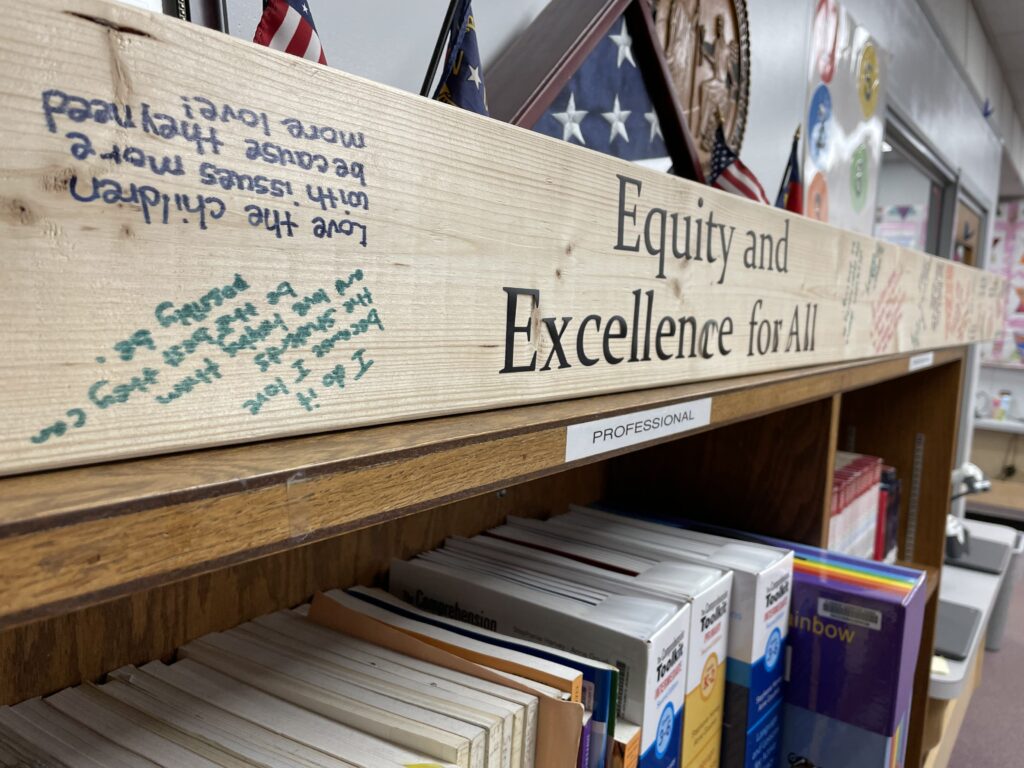

However, Arndt feels that teachers buy in to the impact of personalized learning on student growth. More importantly, they have deeply rooted the shared belief that equity and excellence for all students cannot be achieved without sustaining meaning for relationships with all students.