North Carolina is on a growing list of states that are studying Mississippi’s rising reading scores and discussing how to align reading instruction with the science of reading. That much was clear on Thursday when The Belk Foundation held a “North Carolina and the Science of Reading” event at the Friday Institute.

A large gathering of education stakeholders heard leaders of Mississippi’s movement talk about how cognitive science influenced their policies on reading instruction and how those policies led to a rise from the bottom in national reading scores to the average.

They heard an expert on reading science talk about hallmarks of effective reading instruction.

And they heard from author Natalie Wexler, who focused on reading comprehension — which she says sometimes gets lost among heavy discourse around phonics, phonemic awareness, and the process of teaching kids how to decode written English.

“I want you all to really hold onto … why we share this passion, as we listen to these speakers,” Belk Foundation Executive Director Johanna Anderson said. “Let’s take off team stripes, if that’s even a thing, and listen with fresh, curious ears. Let’s have curiosity be the theme of today.”

Among the crowd were education stakeholders, including representatives from Gov. Roy Cooper and Sen. Phil Berger’s office, at least one state legislator, members of the State Board of Education and a literacy task force it has created, leaders from the Department of Public Instruction, and officials from educator preparation programs, school districts, schools, community colleges, philanthropies, and non-profit organizations.

As the event closed, Anderson asked: What’s next?

The literal answer was a convening of the State Board’s literacy task force, which met afterward in an adjacent room — where debate ensued over the definition of high-quality reading instruction.

The less literal answer remains outstanding, including who will lead the charge to action and determine whether North Carolina can find common ground and common language to better teach kids how to read.

The Mississippi story

While Mississippi’s scores on the Nation’s Report Card show a move from the bottom to the average overall, their fourth-grade reading scores among low-income students (79% of the state’s fourth grade students) rank third nationally, and scores among black students (48% of the state’s fourth grade students) rank seventh. When controlling for those two groups, the rise in fourth-grade reading scores has gone from 39th to 2nd.

Kelly Butler provided a historical overview of policy and instructional changes in Mississippi. She is the chief executive officer of the Barksdale Reading Institute which was created to improve education in Mississippi through a focus on pre-literacy and reading skills.

Butler laid out several critical elements before offering details on Mississippi’s rise, with emphasis on being intentional.

“In many places, we are leaving it to chance by not having the strong policies in place that really require the science of reading to be taught,” she said. “We want to move away from that.”

She talked about the importance of finding common language — “so we can stop fighting each other and get on with the work.” She also said consistency in implementation and a focus on purposeful coaching for teachers were instrumental.

Butler says Mississippi can provide a roadmap for other states and noted that she has heard from about 21 states interested in the Mississippi story.

“It kind of jolts you when you think that folks like North Carolina, California, Massachusetts, and Connecticut are calling Mississippi to find out what we’re doing,” she said. “The stars are lining up, or the tables are turning, or something. We really think there’s a national conversation emerging.”

Butler was joined in her presentation by Kymyona Burk, former director of literacy in Mississippi. Here’s how they said Mississippi pulled off its turnaround, along with where North Carolina is:

| What happened in MS: | What they said about it: | Where NC is: |

| 2000 — Barksdale was founded with a $100 million gift. | This is the largest gift ever given in the nation specifically for literacy. | The philanthropy is spread out, with several funders making grants for literacy instruction. |

| 2002 — Barksdale funded 12 faculty members across eight of MS’s 15 ed prep programs (EPPs). | The goal was for these 12 faculty members to absorb and understand the findings from a 2000 National Reading Panel report and begin to implement them at their institutions. They found that not every EPP was teaching the five components of reading identified in the report, and that over two years the EPPs were spending an average of 20 minutes on phonics. | North Carolina has not done a similar study, though some data are available in the latest Teacher Prep Review. A Community of Practice (CoP) was formed in 2018 in response to a report by then-UNC System President Margaret Spellings, laying out shortcomings in teacher preparation. The CoP hasn’t met since last year, and its future is uncertain. The State Board of Education (SBE) created a literacy task force, and one of its roles is to recommend ways to improve EPP alignment with effective practices for teaching reading. It had been expected to make recommendations to the State Board in March, but that timeline has been extended. |

| 2005 — Barksdale partnered with the MS State Board of Education to create greater focus on literacy instruction at EPPs. | They created course schedules, course objectives, and course descriptions for two classes: Early Literacy 1 and Early Literacy 2. The goal was to standardize reading instruction at all 15 EPPs in the state. | There are no standardized early literacy courses at EPPs, though these issues are being discussed by the SBE literacy task force. Some elementary education programs have taken a similar approach to MS’s. |

| 2007 — Barksdale redesigned its approach to literacy coaches. | Barksdale had been sending about 30 literacy coaches into the state’s 180 schools, but moved to create a demonstration classroom and identified a cohort of students for instruction by Barksdale-trained teachers. By December 2007, data showed that the Barksdale group was outperforming peers. Barksdale began training four principals to test how to scale the program. | At the local level, several districts offer training for their reading teachers. At the state level, the NC State Improvement Project has been training teachers in evidence-based practices for 20 years, averaging about 2,000 teachers trained per year. |

| 2013 — MS passed the Literacy-Based Promotion Act, providing $9 million in funding the first year. | Among other things, the law specifically named the science of reading. The law and the funding allowed the education department to require training for every teacher and administrator in a program aligned with the science of reading (LETRS), to hire literacy coaches to sit in residence at the lowest-performing schools, and to provide testing and accountability for teachers at each of grades K-2 (it had started at grade 3). | Read To Achieve was passed in 2012. While it was based on the same law as MS’s (Florida’s), much of the specificity in MS’s law was lost in the version of RtA enacted. The state does not require training for every teacher and administrator, provide funding for coaches hired by the state, nor name the science of reading. Senate Bill 438, proposed last year, largely tracked MS’s law, but that bill was vetoed. |

| 2013-14 — MS schools increased adoption of a science-aligned curriculum. | “We invest in people — not programs,” Burk said. “When you increase their knowledge about the science of reading and what it takes to teach reading to children, then they begin to adopt programs aligned with that.” | The 2018-19 report on Read To Achieve lists a massive number of curricula and instruction materials used within and across school districts, including many districts using curricula not aligned with the cognitive science. The SBE task force has discussed providing a rubric, such as this one, and has echoed the MS approach of providing information around effective curricula but allowing districts to make their own choices. |

| 2014 — MS Department of Education offered LETRS training to EPP faculty. | Burk said there was strong initial interest, but ultimately, many declined the free training. | |

| 2015 — The Department of Education was restructured to create offices for intervention services and early childhood. | “We’ve worked with our legislature and we have all these components of the law, and we are expecting school districts to do these things and implement these things, but our structure at the department did not even allow us to support them in that way,” Burk said. | DPI has an Exceptional Children’s department for students with disabilities and a Department of Early Learning. Each of these departments, along with leaders from each of DPI’s other departments, are represented on a DPI B-12 council chaired by Deputy State Superintendent David Stegall and Director of Innovation Strategy Angie Mullennix that is studying literacy instruction. |

| 2016 — The state passed a law to add new standards and components to reading law. | The department of education required individual reading plans (IRPs) for each student, raising standards for the student passing rate on reading exams, and every EPP graduate was required to pass a Foundations of Reading exam, with accountability tied to EPPs based on passing rate. | North Carolina does not have IRPs for all students, though that was included in SB 438 and State Board members have discussed proposing this requirement administratively. |

Flaws in comprehension instruction persist

The large body of scientific research on the process of learning to read points to two main aspects: decoding and comprehension.

That research is often called the science of reading. But amid its resurgence in the national discourse, the greatest emphasis seems to be on decoding — which includes learning phonics, phonemic awareness (or the sounds letters make and how to combine them and take them apart), and the process of orthographic mapping, which turns phonemic awareness into reading fluency. Less discussed but just as important, Wexler said, is comprehension — both reading and writing.

“I would argue that the problems with comprehension instruction are, if anything, more pervasive, more widespread, and better hidden than the problems with decoding,” Wexler said. “And much less attention is being brought to bear on that.”

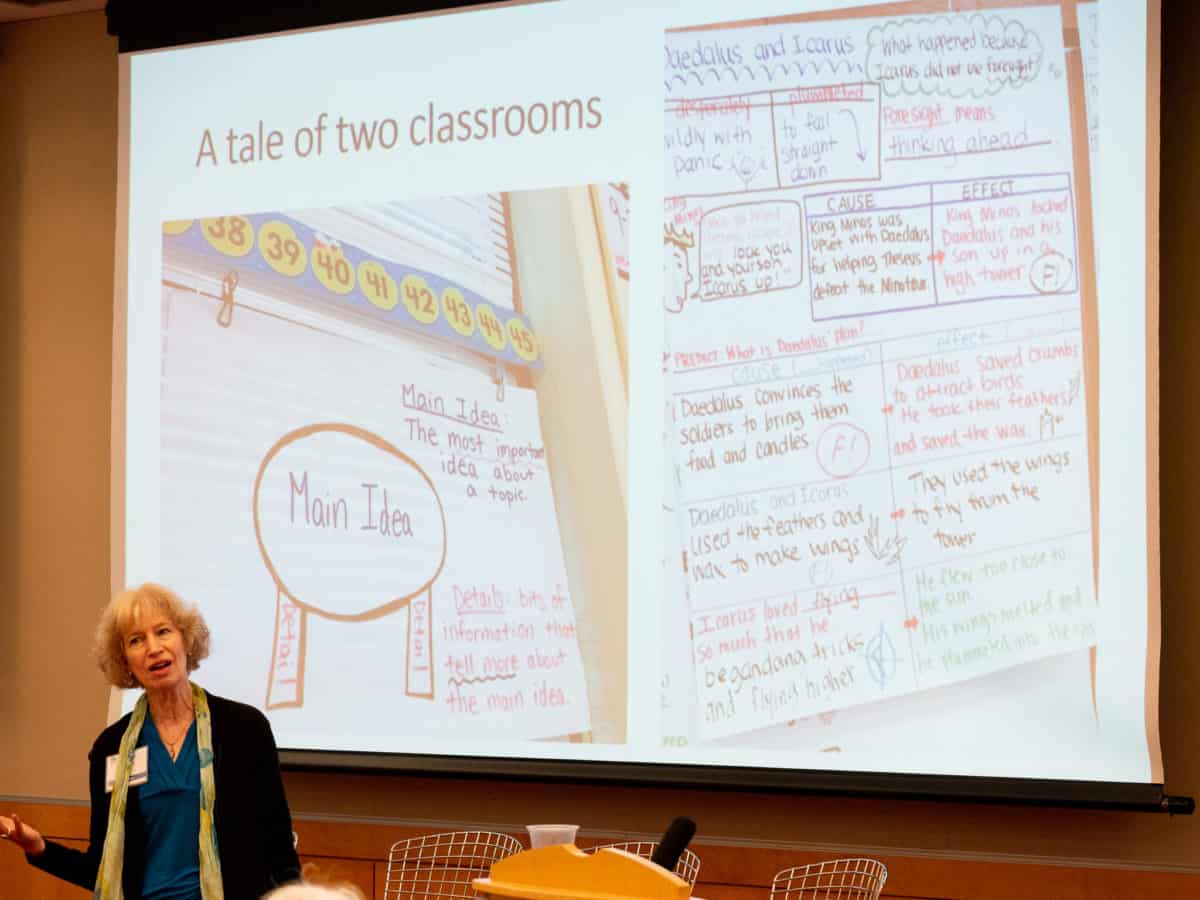

When teachers in early grades approach comprehension, they usually focus on specific skills and strategies. These might sound familiar: finding the main idea, identifying the author’s purpose, making inferences.

Students are assigned texts based on whatever skill or strategy the teacher wants to emphasize, Wexler said. Those texts are based on students’ individual reading levels determined by assessments. A student in third grade might be reading on a first- or second-grade reading level.

“The theory of this approach is that if you diligently practice your reading comprehension skills and strategies on books that are essentially easy for you to read — you get really good at finding the main idea — you’ll be able to apply that skill to any text that’s put in front of you, whether it’s a passage on an end-of-the-year standardized reading test or a textbook you’ll encounter down the road in high school,” she said.

But Wexler said that theory doesn’t take into account an important aspect of comprehension: background knowledge. She shared a 1988 study commonly referred to as “the baseball experiment.” Researchers found poor readers who had prior knowledge on baseball scored significantly higher in comprehension on a text about the sport than skilled readers who didn’t know anything about baseball.

Comprehension depends more on a student’s knowledge of the content, Wexler said, than a student’s reading level.

“There’s really no such thing as an individual reading level,” she said. “It’s going to depend on the topic and how much you know about it.”

Wexler said intense focus on math and reading in elementary schools has left students without much instruction in social studies, science, and the arts — subjects that inform a student’s knowledge base to understand text.

Meanwhile, she said, reading tests are intentionally created to draw from students’ general knowledge instead of specific subjects children are taught in class.

“Those passages on tests assume a lot of background knowledge,” Wexler said. “They’re not connected to anything kids may have learned in class; they’re not supposed to be. They’re supposed to be testing these general reading skills, so test designers try to avoid topics that kids might have learned about in class.”

She said the students without the background knowledge needed to understand those texts are often from less-educated families.

These inequities produce a “snowballing process,” Wexler said, since background knowledge is also linked to better absorption and retention of information. Students show up in high school expected to learn about world history and other complex subjects without the basic knowledge to comprehend content, she said.

Wexler said elementary schools need both curriculum and assessments that are based on content instead of skills to improve reading and student engagement.

“There are untold numbers of teachers and kids out there who are stuck in this false assumption that these kids are only capable of so much,” she said. “We need to unlock all of that wasted potential that’s out there as soon as possible.”

What’s next for North Carolina?

As the State Board of Education and the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) rethink literacy instruction across the state, leaders are struggling to find common ground and common language.

The State Board’s task force on literacy instruction, educator preparation, and professional learning met before and after Thursday’s Belk Foundation meeting to hone its initial recommendations to policymakers. Members heard from DPI officials on the creation of a definition of high-quality reading instruction.

The department’s most recent definition is as follows:

High quality reading instruction, grounded in the science of reading and data-informed, encompasses the five domains of reading: phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. It is structured, explicit, systematic, and multi-sensory, resulting in learners who read and comprehend increasingly complex texts.

The definition is supposed to inform the State Board’s strategic plan for reforming literacy instruction — and give stakeholders and teachers a common starting point.

But several task force members took issue with the proposed definition, as did literacy expert Barbara Foorman — who helped implement reading instruction reforms in Florida, upon which the Mississippi policies were based. Foorman separately consulted for Berger and the State Board last year, and was present at the task force meeting by way of invitation from The Belk Foundation.

“I just think we’re 20 years beyond where that definition is,” she said.

The “five domains” referenced in the definition refer to the five pillars of reading identified in a National Reading Panel report in 2000 that studied the most effective approaches to reading instruction.

Foorman said newer research has broadened the field’s knowledge on what works best. For example, she said, other aspects of language besides vocabulary, including oral language, are important in learning to read.

She also cautioned against creating a strict definition of “the science of reading,” since the body of research is evolving.

“We have the science of criminology, the science of reading; every domain, every field of study has a science,” she said. “But it’s a moving, it’s a growing phenomenon. And I don’t want people to think it’s totally settled.”

Foorman said the only aspects that are “settled” by scientific research are phonemic awareness and alphabetic principle.

The word “multisensory” also brought up concerns.

“It’s not needed, and the danger is it triggers something,” Foorman said of the word, adding that it is commonly associated with a set of curricular materials called Orton Gillingham. “It has a connotation that I don’t think is part of the science of reading.”

DPI K-3 Literacy Director Tara Galloway said that the feedback would be used to tweak the definition and that the language then might be put out for another round of public input. The current definition, she said, was agreed upon by 85% of stakeholders across the state.

“We want this right,” Galloway said. “This is the foundation for what we do moving forward.”

The word “phonics” was also seen by members as potentially divisive and linked to specific sets of materials. Some task force members worried that it might lead to schools searching for phonics resources to simply plug into existing practices.

Galloway said she wants to make sure the language signals to teachers and others that there needs to be broader change in the classroom. She said the two most important words of the definition in her mind were “systematic” and “explicit.”

“What we need is transformation of practices that are happening across the state,” Galloway said.

Vickie Sutton, Greene County’s K-5 literacy coordinator, cautioned the group against insulting teachers and their work.

“I do think we need to be very aware that we can not afford to alienate the very people that we need to implement this,” Sutton said. “They are the ones that are going to be in the trenches doing this work.”

Editor’s Note: The Belk Foundation is a Charlotte-based family foundation that supports public education by strengthening teachers and school leaders, and ensuring that students are achieving on or above grade level by the third grade. Now in its fourth generation of family leadership, The Belk Foundation serves as the public expression of gratitude and commitment shown by the family that created the Belk department store organization. The Belk Foundation had assets of more than $52 million as of September 30, 2017. Since 2000, The Belk Foundation has invested more than $46 million in our state. The Belk Foundation supports the work of EducationNC.