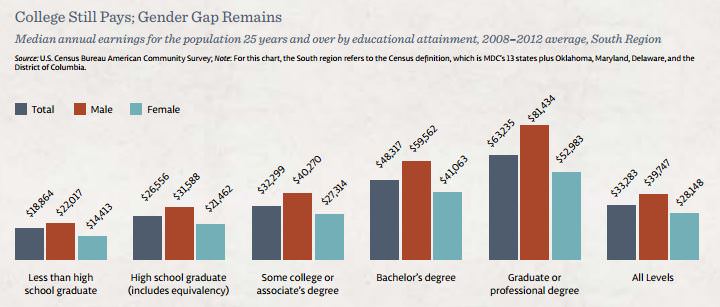

Over the past two decades, data have piled up that show the diminished economic value of a high school diploma.

Any celebration over North Carolina’s highest-ever graduation rate must be tempered by the reality that a diploma no longer serves as a ticket into the middle class.

Middle-skill and high-skill jobs that sustain a middle-class standard of living now require a bachelor’s degree, an associate’s degree, or certified training. The industrial-era economy of the 20th century drove states to expand high schools to the 12th grade; now the digital-economy of the 21st century demands more people educated beyond high school.

A decade ago, North Carolina upgraded its public school reforms by blending high schools and colleges in an attempt to make more students ready for higher education. Gov. Mike Easley appointed an Education First Task Force, which recommended an “innovations fund’’ for high schools, which led to both state legislation and a Gates Foundation grant. Easley branded his initiative “Learn and Earn.” Gov. Bev Perdue followed up with her “Career and College Promise.”

Now, the state has 75 early college high schools serving 15,000 students, as well as North Carolina New Schools that works with local districts to empower high-performing teachers and schools leaders. “To increase the number of students graduating from high school who enroll and succeed in college, North Carolina has established the largest number of Early College High Schools (early colleges) in the United States,’’ says a recent report from SERVE, an education research unit at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Alex Granados reported on EdNC.org earlier this month that, of the 17 schools with high enrollment of students from low-income households that scored an A under the state’s new grading system, 11 are early colleges. SERVE has published research findings that compared the experiences of 938 early college students with 713 students who applied to an early college but didn’t get chosen through a lottery (called the “control group’’ by researchers).

The SERVE research produced these findings:

Finding 1: More early college students were on-track for college.

Finding 2: Early college students earned an average of 22 college credits while they were in high school compared to an average of less than 3 college credits received by students in the control group.

Finding 3: Early college students graduated from high school at a slightly higher rate than the control students.

Finding 4: More early college students enrolled in college.

Finding 5: Early colleges create an environment explicitly focused on college readiness.

In early colleges, students take a combination of courses taught by high school teachers and college-level courses taught by community college or university faculty. Most early colleges are situated on college campuses.

“I think it was an eye opener to the real world and what we were going to be dealing with when we went to a college. And I think I feel more prepared now than … just coming out of a regular high school.” – Student at an early college

They are public schools, but not open enrollment. Students have to choose to apply. Some schools select by lottery, some by their own assessments of which students would benefit. Unlike traditional public high schools, they do not accept all students. Early colleges are not for special-needs adolescents; they are not for high-fliers destined to take Advancement Placement and International Baccalaureate courses as springboards into elite universities. Rather, early colleges accept students from low-income households and from minority populations, students likely to be the first in their family to go to college.

Julie Edmunds, SERVE’s project director for secondary school reform, characterizes early college students more descriptively. They are “the middle that never gets anything.” She says they are “misfits,’’ in the sense that a traditional high school just doesn’t work for them. They are the young women with blue-dyed hair. They include the young black man getting into fights until an observant principal noticed his academic potential and diverted him from the “wrong crowd’’ into an early college.

Early college high schools represent a frontal assault against the cruel barrier of a culture of low expectations –

low expectations of certain students among school administrators and teachers,

low expectations among parents who themselves did not complete high school,

low expectations among students themselves.

“… if I didn’t go to this school, if I were to get out of high school and go to a college, I’d feel like everything is just being bombarded at me… here it’s spaced out. I already have college classes under my belt.” – Student at an early college

“What early colleges can do is force people to think about what these kids can do,” says Edmunds. “They are showing kids can do much more.”

The early success of early colleges has gained them support across party lines. Though the high school-college blending originated during a Democratic administration, the Republican-majority General Assembly has not sought to shift course as it has in other facets of education policy. They are schools of choice, a concept that appeals to Republicans. They are schools that promote reform and help overcome educational disparities.

North Carolina still has room to expand early colleges. As Edmunds points out, more young people apply than seats available. What’s more, she says, the state has the challenge of how to apply lessons learned into traditional comprehensive high schools to imbue them with a strong college-going culture.

Whenever someone tells you that public schools don’t work – or that state government initiatives that cost some tax money inevitably fail – just add early college high schools to the list of reforms that make a difference in the lives of young men and women.